Madhumita Murgia - 'Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI'

So-called artificial intelligence as it affects real human beings.

Patrick Joyce is a social historian, which quite well puts his finger on the pulse of this book: it’s to do with history, partly his Irish heritage, and partly with how he blends the past and the present. Who doesn’t?

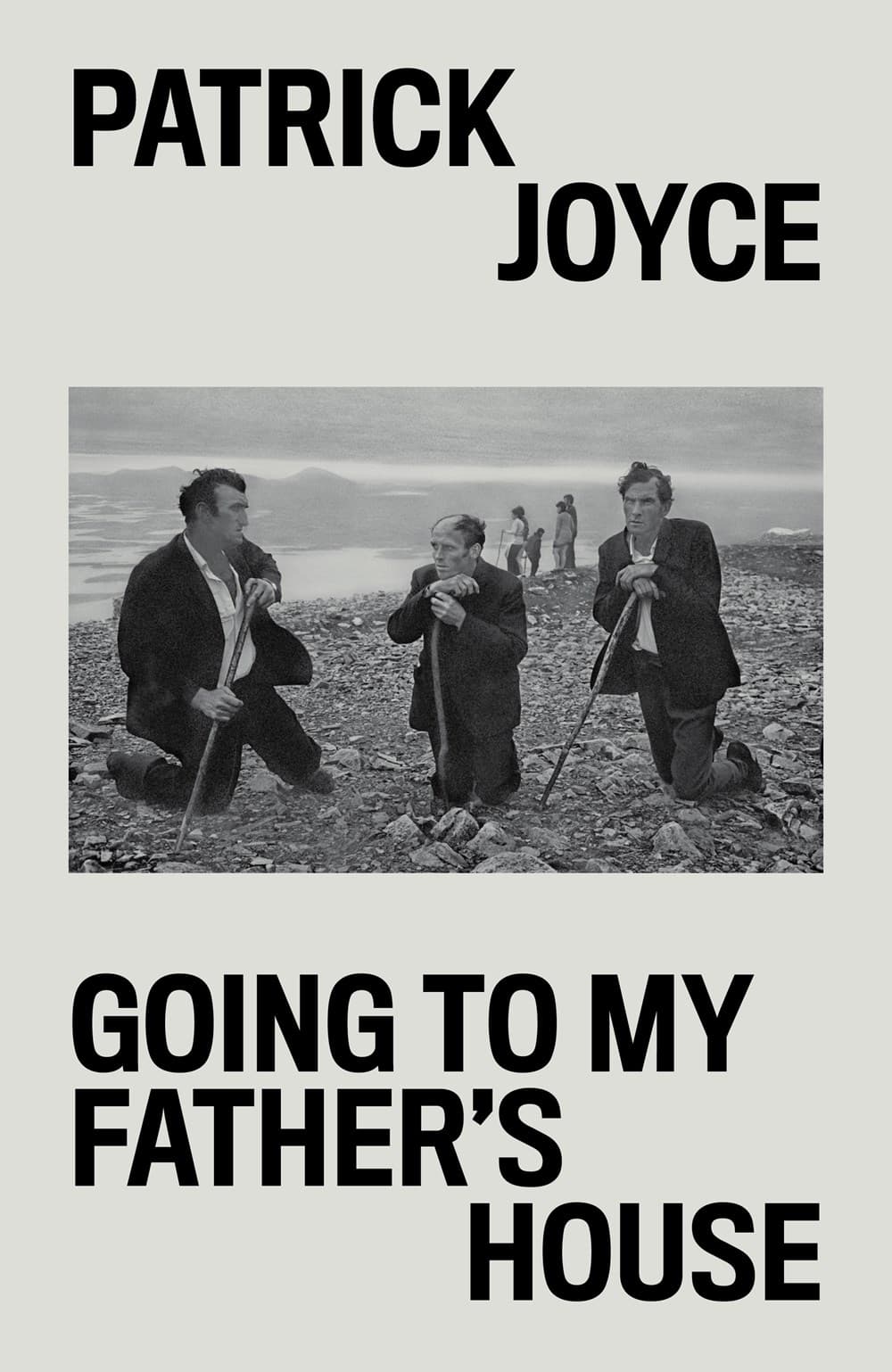

Speaking of which, there’s the cover picture used for this book:

Josef Koudelka, Ireland 1972. Croagh Patrick Pilgrimage. The three men in this image kneel at the summit of Croagh Patrick, which has been a place of Christian pilgrimage for over a millennium and a half. Before then it was a sacred place for perhaps twice that time. Below the summit, and in the background, is Clew Bay, the Atlantic Ocean speckled with islands, drowned drumlins marooned by geological time. Josef Koudelka called this photograph Ireland 1972. It is part of a collection of his work entitled Exiles. In the other photographs in the collection, Koudelka photographed the margins of Europe, margins that are both geographical – Croagh Patrick is at the outermost western limits of Europe – and social. He was drawn to images of gypsies, one of Europe’s most powerful symbols of what it is to be at the margins of an acceptable social life.

The start of the book deals with Joyce speaking of different parts of Ireland, of his father’s land, of how Ireland was cut up and reduced.

By 2015 only one-third of Irish farms were economically viable, while another third only remained sustainable by means of off-farm income. The remaining third face a precarious future, if any at all.

As you see, Joyce also deals in the present day.

There’s also the poetic, the everyday telling of life, in short sentences.

When writing, we converse with ghosts it is difficult to hear back, even when they are benevolent ones.

Speaking of which, this is a fine example of something that nearly seems to have invited a form of gallow’s humour:

The buildings took my father to Portsmouth in 1940. There he was buried alive in a German bombing raid. He was the only one of seven in the house to survive. The physical damage done to his hands and arms left him unable to do the hard but well-paid labour that would have earned us a better life.

I’ve always felt that Irish black humour counters that from Yugoslavia, the dark to stave off - or perhaps, rather, to befriend - harsh truth, in the land where my family on my father’s side came from.

Joyce moved from Ireland to London, England, during the 1950s, with all that entailed:

‘No Irish, no blacks, no dogs’ is now thought of by many to be the title of Johnny Rotten’s first excursion into autobiography, rather than the parlance of Britain’s advertising boards, brazenly apparent in shop and house windows. It is easy now to forget that, as recently as 1965, racial discrimination was perfectly legal in Britain, and that it was not until 1968 that it was outlawed in housing. My generation grew up with the idea that skin colour denoted a form of existence not only different but inferior to ours. Some of us did not buy into this idea, but all of us were marked by it, for how could you be anything else when inhumanity was naturalised, made normal, skin colour ‘natural,’ like the cracked pavements you walked on and the polluted air you breathed? Generations since then have paid the price for those times; making blackness natural then meant making whiteness invisible, so hiding for many decades what is now called ‘white privilege’. A Gallup poll of 1958 reported that over 70 per cent of respondents were against ‘mixed marriages’.

Joyce is good at displaying patriarchy for that it is, on par with religion, and how quickly one had to grow up.

One’s fate in the 1950s was pretty much decided at the age of eleven, when the eleven-plus examination sorted the educational worthy from the unworthy. Only four out of thirty in my junior school class passed the eleven-plus (the preparation for this supposed intelligence test was woeful). I passed the examination; but because there were not enough Catholic grammar schools went to the Cardinal Manning Secondary Modern School for Boys to give it its full title, in St Charles Square, in what is now called Notting Hill. Going to a nonCatholic grammar was possible, but did not for a moment enter into considerations of either my parents or my teachers.

For being a senior and white gentleman, Joyce is intelligent enough to recognise the world around him, the world, for what it is.

In British bookshops, the ‘military history’ section is often among the largest. British football supporters continued to sing ‘Two World Wars and one World Cup’ at the 2010 World Cup, just as they had at the 2006 tournament in Germany itself. This alternated with ‘Ten German Bombers’, sung also by Northern Irish football fans and those of the sectarian Glasgow Rangers. All this might not matter if football was not so much part of the ‘national psyche’. Paul Gilroy has identified the connection between sport and nationalism as a symptom of what he calls ‘postcolonial melancholia’ – a form of mourning for a lost empire. Be this as it may, the armed forces play up unceasingly to all this, for Britain since the war has become an extremely martial country, deluded by the image of plucky victory long ago, and by its continuing pretensions to Great Power status.

Joyce’s words on World War II, on the contemptible ways of White England, in how they celebrate the RAF, colonialism, and religion as long as it keeps themselves up and the rabble down; Joyce displays this masterfully, while also keeping his nose above the waterline: it’s easy to scorn others and very hard to feel just that while keeping a different line in writing; Joyce has managed to show how disdainful, ridiculous, and painful jingoism, racism, sexism, and neoliberal politics are without painting black on white: there’s a certain nuanced sheen over this book.

It’s also a diamond-in-the-rough kind of book. Certain passages feel more globbed together by sense of feel instead of having let sections come together for the sake of coherency, where a theme could have been the deciding factor of a chapter, rather than…what, exactly?

This is not a problem, really, but rather lends toward the stream-of-consciousness form that this book has. Truth in spurts, paragraph after paragraph.

In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag comments on those who have known war first-hand: ‘Why should they seek our gaze? What would they have to say to us? “We” – this “we” is everyone who has never experienced anything like what they went through – don’t understand. We don’t get it. We truly can’t imagine what it was like. We can’t imagine how dreadful, how terrifying war is; and how normal it becomes … Can’t understand, can’t imagine.’

Shirley Baker, Manchester

Shirley Baker, Manchester

The photograph of Manchester is by Shirley Baker – a street photographer, like Roger Mayne, though much less known than him until recently, no doubt because she was a woman. In the background is a new tower building of the University of Manchester Hospital, and to the left of it the massive bulk of the Catholic Church of the Holy Name, built in 1871 to accommodate the armies of poor Irish immigrants still arriving.

It’s not difficult to draw a thinking line between Joyce’s Catholic upbringing in/from Ireland and how things have turned today. It’s horrifying, breathtaking, and nostalgic at the same time.

An example of this is Bet365, an online gambling company, designed to skim punters out of money and concentrate wealth at the top of the company: the old capitalist strategy. Here’s a quote:

Behind Bet365 is the phenomenon that is Denise Coates. She took the gambling side of the family business in hand in 2000. She is the highest-paid female business executive in Britain, and probably in the world, and one of the richest women in Britain. This is not difficult to bring off as, unlike many such companies, hers is family-owned, so that she pays herself. She is a favourite of the tabloids, though she and the company are very private, and in many ways very Stoke: a favourite because, between 2016 and 2019, she collected a total of £817 million in remuneration. The upmarket Guardian was on the case, too, estimating that over the same period she was paid an amount 18,500 times the income of the average woman worker in the city. She owns a Norman Foster–designed house said to have cost £90 million. In 2019, Forbes magazine estimated her net worth at $12.2 billion. Of the house, Piers Taylor, co-host of BBC TV’s The World’s Most Extraordinary Homes, told the Daily Express in 2018: ‘Denise could have done a lot worse. Most new Cheshire millionaires build McMansions: a curious mashup of a super-sized developer house that’s mated with a Las Vegas casino … It is one hell of a lot better than most of the houses that Cheshire footballers build.’

In total, this book is a ride. It is a fairly subdued ride, with no peaks and valleys that will leave you breathless other than by fairly simple storytelling: in this lies Joyce’s strength. He tells things simply, and rather than having his writing style be what jostles your mind afterwards, you think of the things he’s written and let those concepts, images, and descriptions haunt you instead. This is the good haunt.