Madhumita Murgia - 'Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI'

So-called artificial intelligence as it affects real human beings.

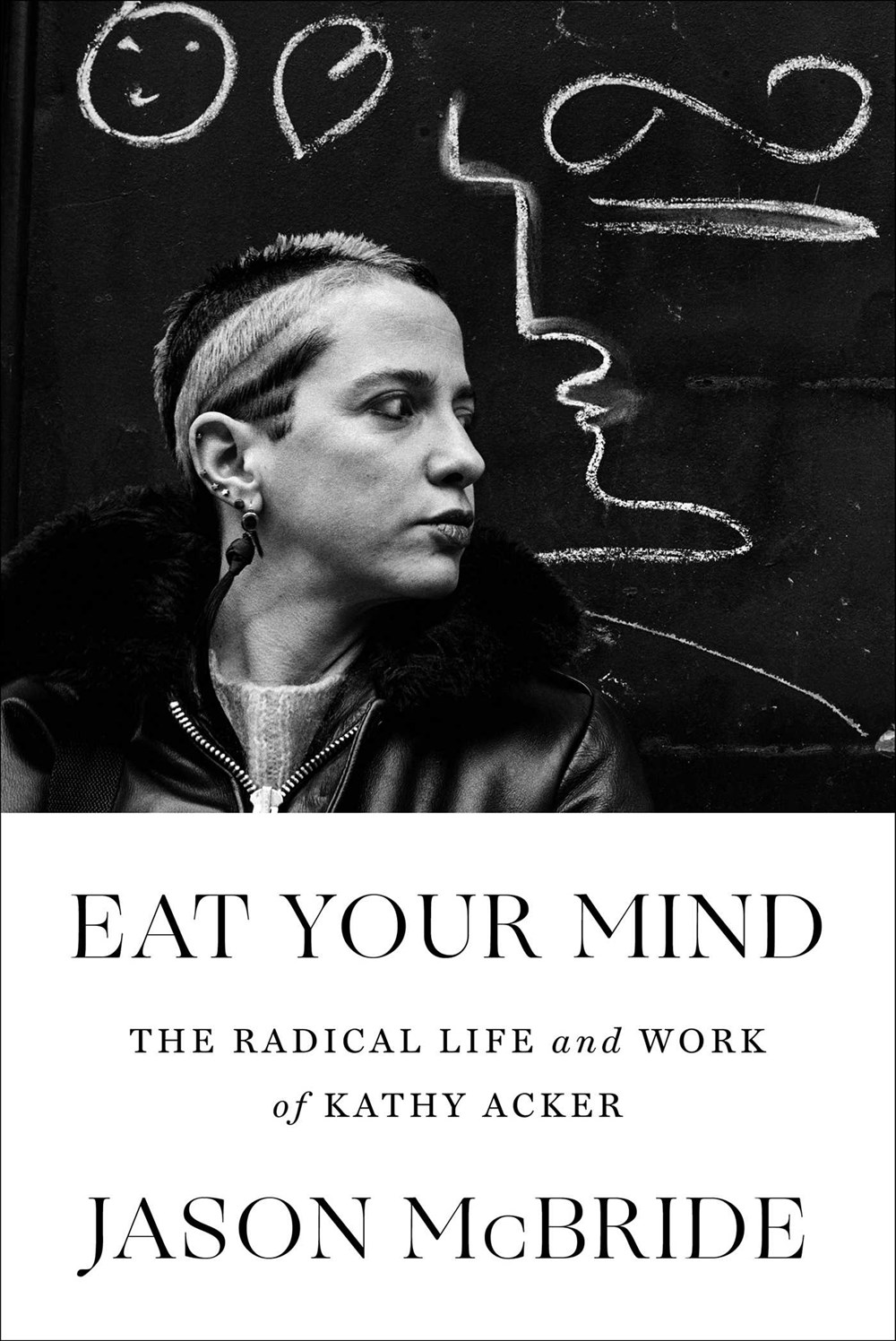

Jason McBride has created a captivating and engaging book on Kathy Acker: her mind, writing, relentnessness, seemingly always-hyperkinetic state, genius, and folly.

Kathy Acker was an artist, a writer, a public figure, a destructive, generative, wondrous, lying, truth-telling person. She was a libertine rich person who acted poor. She wrote her way around sex, liberation, gender, and basically breaking social taboos like others smoke cigarettes, but she did it in style, at a time when there weren’t many people like her around.

Neil Gaiman:

“She cast a long shadow,” he said, “in the way that the first Velvet Underground album did. There’s that wonderful line of Brian Eno’s—‘Only a thousand people bought it, but each of them went out and formed a band.’ The people who read and got Kathy, they went and took some of that out into the world.”

At the very start, Acker kept notebooks, which not only show her formation as a writer but perhaps also her gist, even though there’s far more to her than mere pomp and shock:

Her consciousness was less stream than geyser or cataract. The scholar Claire Finch describes the notebook entries as “a succession of gasps.”

It’s hard for people today to see how groundbreaking could be. She had the beat poets come before her, the modernists before that, etc, but she really turned things on their head. Fearlessness and use of the ‘forbidden’ like it’s everyday was her forté in some ways, it seems.

I say ‘seems’ because I’ve yet to read a single book by Acker.

What? I hear some think (some in the back lines of the room). How can you write a re– Shut yo face! Why not? Did Acker care about prerequisites before writing about something?

She might have. At times. Reading McBride’s book, it appears more that she was fuelled by going against the grain, as if someone saying ‘you can’t do it’, she would have.

She wasn’t just some delusory person going all over the place. She had a head for reading and knew her way around both literature history and the human psyche.

There are some fantastic anecdotes in this book.

Acker often credited Burroughs and Gysin’s The Third Mind, which collects these experiments in one book, with influencing her early writing. She, in fact, considered ‘The Third Mind’ Burroughs’s most important book. It wasn’t published, however, until 1978, long after she’d started publishing.

To Acker, details and reality were seemingly second to the experience of her writing. Things that she claimed to be true were necessarily not that; if it made for better experience: good. If not, too bad. She didn’t particularly care.

Her love for Jean Genet, the author, seems to me symptomatic of her oeuvre:

In her copy of the latter, Acker left a handwritten note to herself, seemingly explaining her choice of Genet as a love interest: “When I fall in love w/ real men, I always get hurt. So why shouldn’t I fall in love w/ whoever I want even if that person’s—miles away, totally inaccessible to me, & I have to pretend I’m someone else to get to meet him once.”

On Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School:

The book skips through several time periods and places and viewpoints, and sections stolen whole-cloth from other works—Guyotat’s Eden, Eden, Eden, Melville’s Redburn, Madame de la Fayette’s La Princesse de Clèves, Sartre’s Sketch for a Theory of Emotions, Pauline Réage’s Story of O, Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past—are spliced together in ways both jarring and jocular. When writing Blood and Guts, she found the selection and arrangement of the Genet sections the most pleasurable part of that experience, and with Great Expectations, she employed this technique with even more gusto. “I really felt I was doing something I loved,” she said. “I’d often take texts that were either sexual or political—usually fairly hot texts, like the beginning of Great Expectations, where there’s that incredible Pierre Guyotat text—and I put these next to the stuff about my mother’s suicide. Now one speaks about ne’s mother’s suicide in a certain way, especially autobiographical material. And one speaks about sex during wartime—which is what Pierre Guyotat is writing about—in another way. I put them both together as if they were the same text. Doing that uncovered a lot of stuff.” The first section of the book is baldly titled “Plagiarism.”

One of McBride’s main fortés in writing this book is keeping a rein on things; a book like this could easily seem scatterbrained, lost, and lose its initial rhythm. It’s a tight book, which takes serious and considerable effort, especially as he’s kept the book flowy, engaging, and engaged throughout. He manages to spawn concern for Acker, in spite of her less favourable sides.

Acker was a renaissance person who made her way and fame across the Atlantic: in England, she became known as a shocker, and appeared wherever, all along writing books. Her Blood and Guts in High School, was, according to author Neil Gaiman, ‘weird and wonderful’, and when he saw her on TV, she scared and intimidated him. All part of her allure, and of her persona.

Acker flitted through relationships, romantic, sexual, others. As befitting himself, Hanif Kureishi nails this while being funny:

Though he never particularly cared for her writing—“a bit unreadable,” he said—Kureishi became a friend, and also an occasional lover. He and Usher would sometimes go to movies with Acker, each sitting on one side of her, holding her hand, and then the trio would head back to Digby Mansions to have sex. After Allen Ginsberg gave a reading at Riverside, the three of them went out to dinner with the poet, and when Ginsberg hit on Kureishi, Acker urged him to seize the opportunity (Kureishi declined). As much fun as Kureishi thought she was, he was also irked by her “incessant, horrible” name-dropping and what he considered her poor-little-rich-girl act. “It was quite vulgar,” he said. “I mean, she complained all the time about what a hard life she had, and how poverty-stricken she was. We came from the fucking suburbs, grew up in the fifties. She went everywhere in taxis. We used to go on the Tube. The idea that you could go in a taxi was so exotic to me.”

Her friendship with author Gary Indiana came to a sharp stop:

This all reached an unfortunate apotheosis with Indiana’s Rent Boy, which came out in 1994. The short, sharp novel is narrated by a hustler/architecture student named Mark, who also works as a waiter at the fictional Emerson Club. The Emerson resembles the Groucho or Soho House, and one of its members is Sandy Miller, a cheap, self-involved, careerist, preposterously attired writer obviously modeled after Acker. “I read one of Sandy’s books,” Mark recounts with palpable contempt. “It was all my cunt this and my cunt that for two hundred pages, stick your big dick in my cunt sort of stuff. But literary, you know. One minute Sandy’s getting banged by an Arab Negro and the next minute she’s a sixteenth-century pirate on the high seas, or Emily Brontë or something. Her writing is real modern.” Rent Boy was published by High Risk, Amy Scholder and Ira Silverberg’s imprint. When they first read the manuscript, they loved it, but they told Indiana he should change the Sandy character somewhat, to make her less identifiable to Acker and other readers. Indiana wasn’t sure how to do that, but they suggested altering his description of her handwriting. He didn’t particularly remember what Acker’s handwriting looked like, so he agreed—and then accidentally ended up describing it with absolute precision: “itty bitty handwriting that looks like a secret code.” Acker was incensed when the book came out, even threatening to sue Indiana. Making matters worse was the fact that she hadn’t been insulted by just one friend, but a trio of them. Many years later, Scholder said she would have still published it—“it’s Gary at his best”—but she wished that she had at least given Acker advance warning. “When she confronted me about that I felt terrible,” Scholder said. “She was right I should have talked to her about it, allowed her to read it before anyone else in the public read it.” Indiana, for his part, didn’t expect it would upset her as much as it did. “I thought she would think of it as a piece of fiction,” he said. “She’d taken everything in her life and put it in her books. If you dish it out as much as she did, you should be able to take it.” After another writer in San Francisco gave the book a good review in a local paper, Acker saw him at a party and threw a drink in his face. Then, three years later, Indiana pressed the bruise again. He included another unmistakable, grotesque Acker-like character in his novel Resentment, a character whose writing is described as “a shotgun wedding of the infantile and the obscene.” The two friends never spoke again.

As part of the afterword to this book, McBride uses the following paragraph, I think succinctly and beautifully:

The British writer Tom McCarthy, in a lecture on Acker that he gave in 2017, put it this way: “It might just be that the final measure of a writer is not so much what they achieve themselves as what they render possible for others.”