Madhumita Murgia - 'Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI'

So-called artificial intelligence as it affects real human beings.

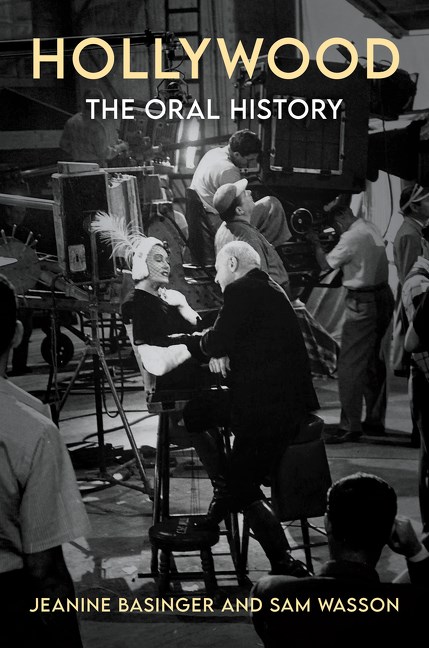

The editors of this book—film historian Jeanine Basinger and film chronicler Sam Wasson—have gone through thousands of transcripts of interviews with Hollywood actors, directors, writers, flunkies, producers, etc. who started working in the early twentieth century, up to people who are still working in Hollywood. The film industry.

The book is sectioned into parts like ‘Silent actors’, ‘The studio workforce’, ‘The end of the system’, and ‘The deal’. Both Basinger and Wasson contribute by adding contextual passages to make stories flow better.

MERVYN LEROY: In those days, anything could happen. If you made a drama, sometimes when you previewed it, it became a comedy. And title writers—if something wasn’t working, they could take a comedy and write a dramatic title and make a drama out of it, and vice versa if it was a drama. You know, when you wrote titles, all you had to do was, when you saw them open their mouths, write a title and stick it in so the audience would know what happened. A lot of good pictures were made that way! It’s true!

The hard thing about these stories is that they’re told by people who are deeply engaged. Some stories might be false. Others misremembered. Still, you see certain red threads, threads that are selected and edited by Basinger and Wasson.

Even if you have the most skeptical and critical eye when reading these stories, there’s both beauty and horror.

HAL MOHR: In those days, when you made a picture, there was no designation of responsibilities. I mean, four or five people would get together and take the script, break it down and talk it out, have story conferences, discuss the thing and make decisions. All of us together. And women, too. Universal sent me out with Ruth Stonehouse. They sent me out with Ruth to be her cutter and to keep her straight on the filming techniques. I was sent out that way with men, too, because I had done directing, photographing, and cutting. I could help. You know, there were women directors then. Besides Ruthie, there were other women directors: Ida May Park, Lois Weber.

LILLIAN GISH: I directed a picture when I was twenty. With my sister, Dorothy. She was the most talented of the two of us, because she had comedy and wit. I thought I could bring it out as a director. I was too busy acting to do much more directing, but there were many women directors . . . and of course, writers, too . . . in the early years. The opportunity was there for a woman if you wanted it. It changed later, after sound came in, I think.

Things that seem weird now were the norm then.

KING VIDOR: I remember that with the silent films, the director was always asking the cameraman, “What speed? What speed are you going?” And they had a little speedometer on the camera. You don’t see that anymore. Films were shot at sixteen frames per second and projected at about eighteen to twenty frames. Charlie Chaplin said to me once, “Nobody ever saw me run around, turn the corner, as I actually do it, because those cameramen would drop down to half speed.” That slow cranking speeded him up double, made him faster. Everyone was constantly utilizing different speeds on the camera to achieve a sense of “hurry up.” Even Griffith did it. In Birth of a Nation, he has horses traveling at seventy miles an hour pulling chariots. After the interlock came in, everything became twenty-four frames per second and it was locked down.

There’s a lot of funny anecdotes throughout the book. One example:

RIDGEWAY CALLOW: From the point of view of assistant directors, he was indeed a tyrant. He was the most sarcastic man I have ever worked for, and I did several pictures with him in the capacity of “herder.” In the early days of the picture industry—that is, before the formation of the Directors Guild—whenever they filmed mob scenes, “herders” were employed to help out the few assistant directors assigned to the show. Although termed “herders,” they were actually extra assistant directors for crowd control. In productions with complicated action of the extras, one herder was employed for every hundred extras. The biggest use of herders in those lush days, was, of course, DeMille, who specialized in epics with “casts of thousands.” DeMille was a master in mob control. He demanded complete silence when he spoke, so much so that one could hear a pin drop. He was addressing his mob one day when he caught an extra talking to her friend in the background. “When I’m talking, young lady, what do you have to say that’s so important?” The girl in question was a well-known extra by the name of Sugar Geise, an ex-showgirl and a great wit. Bravely, she spoke up. “I only said to my friend, ‘When is that bald-headed son of a bitch going to call lunch?’” There were a few apprehensive seconds of silence. Then Mr. DeMille yelled, “LUNCH!” So he did have a sense of humor.

Then there are origin stories:

RICHARD SYLBERT: William Cameron Menzies was the greatest designer that ever lived, the father of the words production design. He didn’t invent that title. David O. Selznick gave it to him. He wanted to bring him in to do the designs for Gone with the Wind. And there was already an art director on the film, so they asked Selznick, “What are you going to call him? Art Director Two?” He said, “No, no, we’ll call him the production designer.” That’s where the term came from.

From the Hollywood of old to the 1970s:

PAUL SCHRADER: In Japan, if a man cracks up, he closes the window and kills himself. In America, if a man cracks up, he opens the window to kill somebody else. And that’s what’s happening in Taxi Driver.

Money started flowing in; film studios started becoming banks more than creative pots.

MEL BROOKS: I don’t want to give twenty-five points to a star. For what? They’re only there for three weeks. I’m there for two years.

JOHN PTAK: Columbia is one of the last studios to be taken over and run by corporate thinking. The rest of the studios are really very large corporations that are in many businesses, especially Universal, which even owns a savings and loan.

SUE MENGERS: Therefore they’re not as adventurous as they were when they were going through their youth syndrome.

JOHN PTAK: In 1936, Warner Bros. made sixty pictures. In 1940, they made forty-five. In 1950, they made twenty-eight. And in the last twelve years, it’s vacillated between thirteen and twenty-two.

DAVID PUTTNAM: And I see the day when a lot of the things that I treasured as a kid have ceased to exist, because they don’t make any economic sense in a worldwide corporate environment.

JACK NICHOLSON: Anybody who had a pancake at the International House of Pancakes on Sunset when it first opened and then goes there today understands why conglomeration deteriorates the quality of the product.

All in all, this book is a look back at highlights and lowlights that are related to Hollywood. There’s loads of industry talk in this book, funny recollections, bad memories, and overall, a lot of witty comments. It’s a long laugh. Should be, the book is almost 800 pages long.

Keep a cool head as you’re reading it, and you’ll get a lot of insight. Film students probably know most of this already, but there’s enchantment to hear straight from the mouths of people who were and are there.