Madhumita Murgia - 'Code Dependent: Living in the Shadow of AI'

So-called artificial intelligence as it affects real human beings.

I didn’t explain myself beyond that. No one asked me to do so.

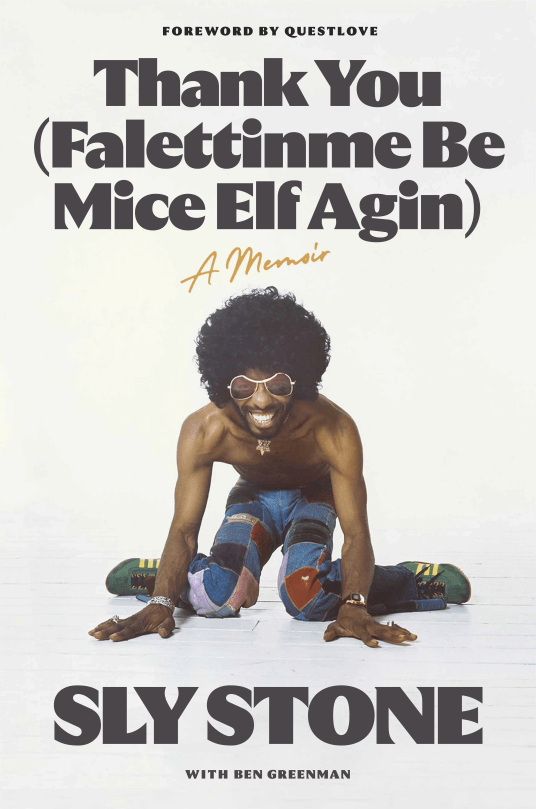

Finally, Sly Stone uncovered: one of the front figures of funk releases his autobiography, and it’s about as elusive as the man himself.

What can I say to all of that? Yes, no, no? No, yes, no? Maybe I was standing on a chair instead of the top of the stairs when I came down to warn people about the other dealer’s stash. Maybe I asked Bubba to get me a lighter instead of a phone book, or maybe he was holding a newspaper instead of a gun. Maybe the girl was half-Japanese. The details in the stories people tell shift over time, in their minds and in mine, in part or in whole, each time they’re told. That’s what makes them stories. Telling stories about the past, about the way your life crosses into the lives of those around you, is what people do, what they have always done. Those people aren’t trying to hurt you. They’re trying to set the record straight. But a record’s not straight, especially when you’re not. It’s a circle with a spiral inside it. Every time a story is told it’s a test of memory and motive. Telling stories isn’t right and it isn’t wrong. It isn’t evil but it isn’t good. It’s the name of the game but a shame just the same.

Sly and the Family Stone became one of the most commercially successful and unique music acts in the world. For a time, they released easy-going funk that was as catchy as it was complex; Sly was, rightfully so, at times tagged as the Brian Wilson of funk; they both made music that seemed easy but was complicated. Well-crafted tunes, explosive stage shows, and a lot of groove and variation wasn’t enough: at the peak of their powers, they released There’s A Riot Goin’ On, a seminal nail in the coffin of Uncle Sam, pretty much in the vain as what Marvin Gaye did when he released What’s Going On; both were recorded around the same time, which says something about white oppression of Black America.

Sly Stone seemed enigmatic to the general public: he didn’t always feel like he had to explain himself and didn’t play into the hands of popular media. He started doing drugs, caught a reputation for cancelling gigs at the last minute, and stopped making hits. He nearly completely stopped doing interviews.

So, to paraphrase Marvin Gaye: what went on?

Sly Stone’s autobiography is a chronological patchwork of thoughts and non-explanations that make up a book that isn’t written to cater to anybody. Stone’s tone is laid down from the start:

Back in 1971, in a song called “Time,” I wrote about how time moved and grew. You can speed up time or slow it down but you can’t stop it. You can try to see through time but it thickens. “Are you dense?” I once asked a reporter. Time is. I think back through it all, through the parts of time I still hold and the parts that have slipped away. I can still hear a note bouncing out of an electric piano in 1966. I can still see the hem of a dress rising in 1970. I can still feel the lights on my face as I walked onstage in 1972. Other memories are harder to grasp. An afternoon at an airport in a city. I know that I once knew the name of the woman at the counter, because I said it to her in a way that made her laugh. But it’s gone. I’m not even sure of the city: St. Louis? Today I thought of a Bible verse I haven’t thought of in years, and it came to me completely, without a piece missing. John 3:1: “Now there was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews. He came to Jesus at night and said, ‘Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him.’” Why that verse? Can’t remember. Maybe it’ll come to me tomorrow, maybe the day after. There’s no hurry. I am taking my time. Have you taken yours? The sun comes up, goes down, comes up again. I’m not trying to stop the day. I know what makes me strong.

Stone paints a pretty psychedelic picture of his life, possibly without trying to act cool; he lets his music bring the cool.

Learning was looking. There was a guy in the church who played guitar. What he did with it was amazing, six strings and an infinity of things. I watched him like a hawk. He wasn’t a mentor. I don’t even know if I spoke to him. I just saw what he did and tried to figure out how to do the same and more. Guitar stayed with me, but I was always looking to whatever was next, taking up the bass, picking out songs on the piano. I felt incomplete without an instrument, or maybe it’s more to the point to say that I only felt complete with one. When I went out into the world, I was surprised to see people who weren’t carrying instruments. I wasn’t sure what they did instead.

In his early days, Stone started DJing and, turns out, he was really good at it; he got a fan club because of how catchy and unique he acted on the radio:

At first my KSOL show played mostly R&B and soul, like the call letters said. But 1964 brought a sea change from across the sea. When the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964, they put everything in the rearview mirror. I didn’t see that show, but I saw how people talked about them after that. I couldn’t ignore them on the radio. I didn’t want to. Whatever was in the air went on my airwaves: not just the Beatles but the Stones, Bob Dylan, Mose Allison. Some KSOL listeners didn’t think a R&B station should be playing white acts. But that didn’t make sense to me. Music didn’t have a color. All I could see was notes, styles, and ideas. I tried to learn from it. I loved the Beatles for their melodies and their lyrics and their tight harmonies. And Bob Dylan, well, he was only one guy, working with just voice, guitar, and harmonica. It was so little to go on, or at least that’s what people thought, but they didn’t hear how dead serious he was about what he was doing, even when he was joking. He pushed his mind at you through his music. After I introduced a record, I would sit at the piano and play along with it. It was an exercise, and it strengthened me. You cover other songs in your mind and eventually you’ve got it covered. Sometimes I would even decide that the original act had taken the arrangement in the wrong direction, and correct course. As soon as the song ended, I was back at the microphone. I started to get known around San Francisco because of KSOL. I had a following and a fan club, the Magnificent Stoners. In on-air promos, a female voice read out a membership offer, which included an official card and a signed photo of me. She left a blank space for the station’s mailing address and I filled it in, using a high voice that didn’t quite match hers. “1111 Market,” I would say in that high voice, and then come back in as myself: “You’re gonna have to do something about your voice, Jo. It changes right in the middle of a sentence.”

Stone came from the kind of background that made it clear that success wouldn’t come easily; not only did he work a lot in the studio but he worked his band:

We worked hard from the start. We practiced hard to make perfect. I was clear about that with the group. If you were only going to get one shot—at a label signing you, at a hit record—you had to make sure that it found the bullseye. That’s what I was aiming for. The arrow was in the bow. I rehearsed the band every day, didn’t matter if it was Christmas or New Year’s or someone’s birthday. The rehearsals went on as long as needed. Bring a lunch, Freddie used to say. That was the only way to get better and getting better was the only way to get best. After a few months, the late weekend shows started to get a little extra shine on them. People came up from Los Angeles and sometimes even farther.

Stone’s world view was so prolific and multi-coloured and allowed nearly any listener to understand that he only wanted to convey his message, regardless of what that message was. His music made it across every border and beyond. Stone knew his self-worth and why. This paragraph is typical in relation to how Stone often tells things in the book:

What really made it clear to me was when David Kapralik gave me a Stellavox tape recorder, one of the best in the world. This is a nice motherfucker, I thought. Why would you give that to me? But I didn’t ask him. I asked myself. And then I answered myself: Because I kicked ass.

Parts of the book are simultaneously funny and insane:

There were, as always, dogs. Everyone in and around the band had them: Jerry had a Great Pyrenees, Larry had a Russian wolfhound. At Coldwater, I had a bulldog named Max, a great dane named Stoner, and a schipperke named Shadow. At Bel Air I had my favorite dog, a pit bull named Gun. He was my best friend. He was crazy. He would chase his tail in circles, not for a minute or for an hour but forever. He couldn’t sleep. At first people thought he had been stung by a wasp but you don’t get stung by a wasp forever. When it became clear the problem was something larger some of those same people said he needed to be put down. Then a suggestion came in that we dock his tail so that he would have less to chase. That settled him down, not completely but enough. Gun was small when he was a puppy, like any dog, but when he was grown he was really grown. He must have weighed sixty pounds, and it was solid muscle. He and I ran the house. We would go through halls, him on a leash, me holding it, looking for people. It was a game of hide-and-seek, though the seeking happened before anyone could hide. Bobby Womack was afraid of Gun, so when he heard us coming he would go behind furniture or into closets. Once I went into a room and saw Bobby crouched up on a pool table. He put a finger to his lips to shush me up. I winked at him and walked out but I don’t know what he was thinking. Gun could have gotten up on top of that table no problem. I also had a baboon named Erfy, meaning earthy. I forget where I got him. Baboon store? Erfy used to tease Gun and then, just as Gun’s temper was spilling over, leap away, higher than a pool table. One day Erfy jumped away too slowly. Gun lunged and got a baboon foot in his jaw and then more than that. He didn’t just catch Erfy. He killed him. And he didn’t just kill him. He forced him to have sex after he was dead. I didn’t see it myself but I heard about it from everyone.

Part of Stone’s unique way in storytelling does slip over from songs written fifty years ago. He can deliver a story by not letting the negatives turn a drink acidic and instead ferment in your head:

Everyone gets their hair done. I went to get mine done at a place named Huff’s Fashionette at Fillmore and Geary. Back then the neighborhood was still the real Fillmore, houses, clubs and bars, lots of black faces. Within a few years, it would be a site of urban redevelopment, which meant clearing our old buildings and replacing them with new expensive ones, clearing black faces and replacing them with whiter ones. A sad story but it hadn’t happened yet.

Stone does, at a few times, flesh out the live experience of playing music, and he tells it simply, in a way that interviewers haven’t asked him to do. It’d be really interesting to interview Stone with open-ended and precise questions:

We were building to “I Want to Take You Higher.” By now it was past four in the morning, still dark, but I could see more of the crowd in the predawn light. God damn. Even those I didn’t see I could sense, between the smoke and the sound. I was thinking what would happen if I said something and they all said it back. What would that sound like? What would it be like? So I tried it. I took the microphone and spoke to everyone. “What we would like to do is sing a song together. And you see what usually happens is you got a group of people that might sing and for some reasons that are not unknown anymore, they won’t do it. Most of us need approval. Most of us need to get approval from our neighbors before we can actually let it all hang down. But what is happening here is we’re going to try to do a singalong. Now a lot of people don’t like to do it. Because they feel that it might be old-fashioned. But you must dig that it is not a fashion in the first place. It is a feeling. And if it was good in the past, it’s still good. We would like to sing a song called ‘Higher.’ And if we could get everybody to join in, we’d appreciate it.” I sang, “I want to take you higher,” and they sang back the last word, “higher.” All of them. Damn. We kept it going. I kept it going. “Just say ‘higher’ and throw the peace sign up. It’ll do you no harm. Still again, some people feel that they shouldn’t because there are situations where you need approval to get in on something that could do you some good.” Want to take you higher went out. Higher came back. What the word meant widened. It wasn’t just keeping yourself up with a good mood or good drugs. It was defeating anything that could bring you down. It was an instruction how to go over your problems. It was a solution. “If you throw the peace sign up and say ‘higher,’ you get everybody to do it. There’s a whole lot of people here and a whole lot of people that might not want to do it, because if they can somehow get around it, they feel there are enough people to make up for it. On and on. Et cetera. Et cetera. We’re going to try higher again and get everybody to join in we’d appreciate it. It’ll do you no harm.” Want to take you higher / Higher. A wave crashing onto the shore of the stage. Way up on the hill … Want to take you higher! / Higher! Want to take you higher! / Higher! Want to take you higher! / Higher! The call, the response. It felt like church. By then the film crew was fully in place. The horns went up into the sky.

You make your own history in an autobiography, unless you do it like Beastie Boys, and allow others to add their stuff. On the other hand, even they controlled their story entirely and wouldn’t publish something they weren’t happy with. Having said that, it’s kind of beautiful to see how Stone portrays his love for the fellow human:

On the morning of September 11, 2001, someone from New York called to tell me to turn on the TV. I did. My first thought was what the fuck? It was my second thought too. I didn’t know what I was seeing. I thought it was a war. I wanted to be prepared, so I bought camouflage clothes, more guns, gas masks. The days afterward were quiet. All the planes were out of the sky. But the damage had been done. People applauded Bin Laden because they hated the United States. A few years later, people applauded the capture of Saddam Hussein because they hated Bin Laden. They weren’t the same people but they were doing the same thing. And if there was no applauding on your side, you could be sure that there was applauding on the other side. None of it made sense. Why did people feel such excitement at the idea that we weren’t all on the same side? I was never going to be at peace with that.

Today, Stone lives a slow life, having cemented most of modern-day funk. His work should inspire gratitude in a lot of artists, in music and beyond.

The book works and doesn’t. It’s not a vehicle like other biographies. If you read this, expecting ‘Family Affair’, you’ll probably get surprised by getting the rest of There’s A Riot Goin’ On; as rock documentaries go, this isn’t The Dirt written by Neil Strauss. In other words: this isn’t a regular book, even though it is chronological.

I wish we’d gotten a bit more of Stone’s inner mind. I wish some paragraphs would have gone on for even longer; it all leaves me thinking Stone is a guarded person, even though he might not be. It might just not be because anyone asked him to explain shit.

Let’s leave with a final quote from the book, where Stone mentions part of his gig at the Coachella music festival in 2010. This might say a lot more about Stone than he intended:

I sang along with a song called “If I Didn’t Love You” which sketched out a bad relationship. Another one, maybe not finished, opened with a scene of a young soldier terrified in the bushes, trained in patriotism and warfare but not courage or conscience. I was on the edge of the stage on my back, then on my feet with my back to the crowd. The band didn’t know what to do or how to do it. They tried to follow me but I hadn’t led them to any of it. Fuck rehearsal.