Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

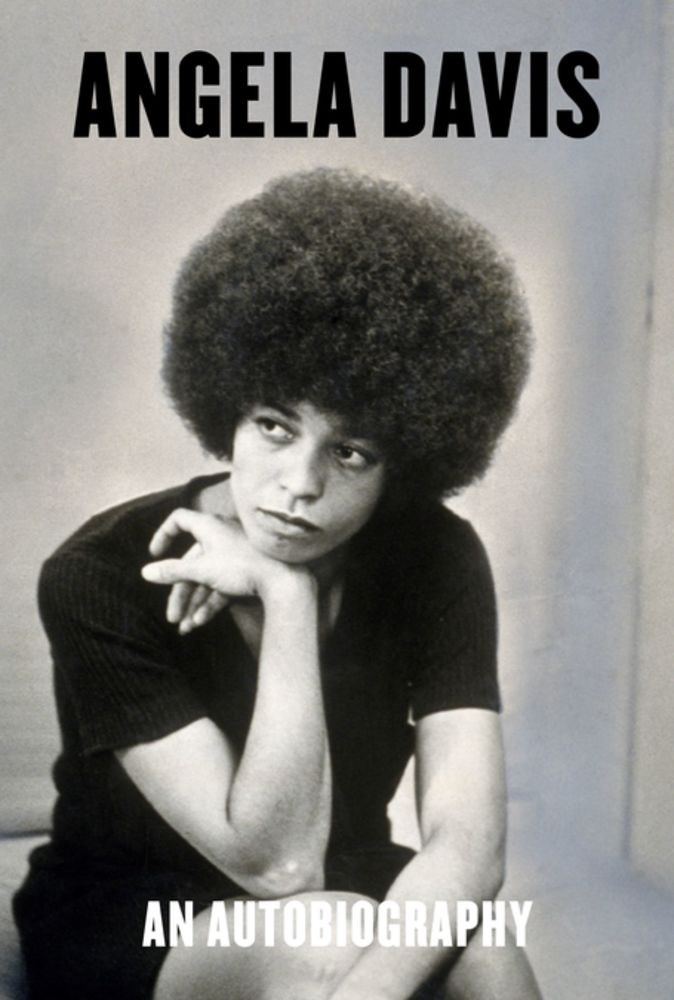

Angela Davis lives. Even if she were dead, she would be so much more than alive simply through her intellectual deed, legacy, and actions. To me, she’s always seemed like this cool, breezy, and intellectual person, but I didn’t get into her until about ten years ago, after seeing a documentary about The Black Panthers1.

I love the myth-making at the start of this book:

In a turnpike motel on the outskirts of Detroit, I turned on the television to watch the news. “Today, Angela Davis, wanted on charges of murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy in connection with the Marin County Courthouse shootout, was seen leaving the home of her parents in Birmingham, Alabama. She is known to have attended a meeting of the local branch of the Black Panther Party. When Birmingham authorities finally caught up with her, she managed to outrun them, driving her 1959 blue Rambler. . . .”

This is very much curtailed by Davis’s view of reality: this book is edited by none other than Toni Morrison. It does actually breathe life throughout, which would probably have happened even if Morrison wouldn’t have been involved. But, still.

Davis tells a straight story that starts with her getting thrown in jail because of her involvement with communism and The Black Panthers. To read about how she and other Panthers were persecuted by police and the FBI (who ran COINTELPRO, a murderous psyops project designed to smash the Panthers) is harrowing.

Davis’s strength in writing comes through in her speaking. She’s almost 80 years old and brings utmost clarity paired with profound insight. Davis is, to me, like reading and hearing Simone de Beauvoir mixed with Noam Chomsky, but she carries a singular tone: that of truth born from empathy, care, and intellectuality.

She describes even the most chaotic situations with a stillness that puts everything in perspective; she is able to freeze the frightful and put it in perspective, to compare it with how much better people in power have it, and why. Ultimately, Davis leads the reader to their own insight, even while shepherding us. The reader is treated like an intelligent person. Even her worst enemies can’t defeat facts. I suspect that this is why COINTELPRO was created, executed, and murderous.

In prison:

One evening, after lock-up, a loud question broke the silence. It came from a sister who was reading a book I had lent her. “Angela, what does ‘imperialism’ mean?” I called out, “The ruling class of one country conquers the people of another in order to rob them of their land, their resources, and to exploit their labor.” Another voice shouted, “You mean treating people in other countries the way Black people are treated here?” This prompted an intense discussion that bounced through the cells, from my corridor to the one across the hall and back again.

Davis, growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, was subject to Jim Crow-type laws, remnants, and naturally also racism.

If, in the course of an argument with one of my friends, I was called “nigger” or “black,” it didn’t bother me nearly so much as when somebody said, “Just because you’re bright and got good hair, you think you can act like you’re white.” It was a typical charge laid against light-skinned children.

The off-campus social life of the Black middle class continued undisturbed— except for the usual, routine racist incidents. For instance, one Sunday some friends and I were driving home from the movies. Among those in the car was Peggy, a girl who lived down the street. She was very light-skinned, with blond hair and green eyes. Her presence usually provoked puzzled and hostile stares because white people were always misidentifying her as white. This time it was a policeman who mistook her for a white person surrounded by Black people. And just as my friends were about to drop me off in front of the house, he forced us over to the side, demanding to know what we “niggers” were doing with a white girl. He ordered us out of the car and searched all of us, except Peggy, whom he separated from the group. In Alabama at that time, there was a state statute that prohibited all except economic intercourse between Blacks and whites. The cop threatened to throw all of us in jail, including Peggy, whom he called a “nigger lover.” When Peggy angrily explained that she was Black like all the rest of us, the cop was obviously embarrassed. He worked off his embarrassment by harassing us with foul language, hitting some of the boys, and searching every inch of the car for some excuse to take us to jail. This was a routine incident, perhaps even milder than most, but no less enraging because it was typical.

There’s no denying Davis’s effective and sobering paragraphs.

She discovered Marx and Engels’s The Communist Manifesto and attended lectures on Marxism. She tells of James Baldwin lecturing. Of discovering the world.

Then her travels started, going to Germany, learning the language, going to France, delving into French literature, philosophy, and politics, at point in time when all of these topics intertwined.

I decided to major in French. That year I immersed myself totally in my work: Flaubert, Balzac, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and the thousands of pages of Proust’s A La Recherche du Temps Perdu. My interest in Sartre was still quite keen—every spare moment I could find, I worked my way through his writings: La Nausée, Les Mains Saks, Les Séquestres d’Altona, and the rest of the earlier and later plays, and the novels comprising the sequence Les Chemins de la Liberté. I read some of his philosophical and political essays and even tried my hand at L’Etre et le Néant. Since I had to contend with the isolation of the campus in one way or another, I decided to make constructive use of it by spending most of my waking hours in the library or in some hidden place with my books.

She not only contacted Herbert Marcuse, the famous philosopher, but was one of his students and became his friend..

This allegory is absolutely beautiful, drawn from her time in the French town Biarritz:

Not long after our arrival, a curious thing happened in the abandoned city: there was a sudden, massive flea invasion, the likes of which the working people of Biarritz had never seen before. For days, it was impossible to find a single patch of land or air uninfested by fleas. In our classrooms, the teacher could hardly be heard over the constant scratching. People scratched in cafés, movie theaters, bookstores, and they scratched just walking down the street. People with sensitive skin were beginning to look like lepers, their arms and legs covered with infected bites. Like everyone else’s, my sheet was covered with little spots of blood. If Ingmar Bergman had done a movie on the oppressive, parasitical tourists who come to Biarritz, and had included the flea invasion in his script, critics would have written that his symbolism was too blatant. In this city in its odd position of trying to recuperate from tourists and fleas—in this group of typically American students that without my presence would have been lily-white—my old familiar feelings of disorientation were rekindled.

Then, the birth of the Black Panther Party:

Watts was exploding; furiously burning. And out of the ashes of Watts, Phoenix-like, a new Black militancy was being born. While I was hidden away in West Germany the Black Liberation Movement was undergoing decisive metamorphoses. The slogan “Black Power” sprang out of a march in Mississippi. Organizations were being transfigured—The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, a leading civil rights organization, was becoming the foremost advocate of “Black Power.” The Congress on Racial Equality was undergoing similar transformations. In Newark, a national Black Power Conference had been organized. In political groups, labor unions, churches, and other organizations, Black caucuses were being formed to defend the special interests of Black people. Everywhere there were upheavals. While I was reading philosophy in Frankfurt, and participating in the rearguard of S.D.S., there were young Black men in Oakland, California, who had decided that they had to wield arms in order to protect the residents of Oakland’s Black community from the indiscriminate police brutality ravaging the area. Huey Newton, Bobby Seale, li’l Bobby Hutton—those were some of the names that reached me. One day in Frankfurt I read about their entrance into the California Legislature in Sacramento with their weapons in order to safeguard their right (a right given to all whites) to carry them as instruments of self-defense. The name of this organization was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

It became both apparent and obligatory for Davis to become an activism. She is a person who would never be satisfied with philosophising behind a desk; well, she may have been, if it hadn’t been for what happened to people and demanded justice and righteousness. In other words, no, she would never be able to sit still.

Her words about sexism sadly still ring through, from all types of men against all types of women:

I became acquainted very early with the widespread presence of an unfortunate syndrome among some Black male activists—namely to confuse their political activity with an assertion of their maleness. They saw—and some continue to see—Black manhood as something separate from Black womanhood. These men view Black women as a threat to their attainment of manhood—especially those Black women who take initiative and work to become leaders in their own right. The constant harangue by the U.S. men was that I needed to redirect my energies and use them to give my man strength and inspiration so that he might more effectively contribute his talents to the struggle for Black liberation.

I’ll include this brilliant paragraph that tells us a bit of how Davis thinks:

The era of massive national conferences was still in full force. In July 1969, movement activists, Black, Brown, and white, from throughout the country, converged in Oakland, California, to attend a conference called by the Black Panther Party to found a United Front Against Fascism. The organizational theory behind the conference was excellent: people with various ideologies—the broadest possible representation of people— joined together to forge a United Front to combat the increasingly ferocious repression. But there were problems with the conference, and I was perhaps overly sensitive, since I had just recently been forced to break my relatively close ties with the Panthers. The basic difficulty, I thought, was that we were being asked to believe that the monster of fascism had already broken loose and that we were living in a country not essentially different from Nazi Germany. Certainly, we had to fight the mounting threat of fascism, but it was incorrect and misleading to inform people that we were already living under fascism. Moreover, the resistance dictated by such an analysis would surely lead us in the wrong direction.

First, in seeking to include absolutely everyone who had an interest in overthrowing that fascism, we might be pushed into the arms of the liberals. Our revolutionary thrust would thus be blunted. And if we were not led in that direction, we would be pressed toward the opposite end of the political spectrum. For, if we believed we were living under genuine fascism, it would mean that virtually all democratic channels of struggle were closed and we should immediately and desperately rush into the armed struggle. In many of the speeches, the word “fascism” was used interchangeably with the word “racism.” Certainly, there was a definite relationship between racism and fascism. If a full-blown fascism ever erupted in the United States, it would certainly ride on the back of racism in much the same way that anti-Semitism provided the handle for German fascism in the thirties. But to think that racism was fascism and fascism was racism was to cloud the vision of those who were attracted to the struggle. It was to hamper their own political development and to impede the organized mass fight against racism, against political repression—and especially in defense of the embattled Panthers. In the midst of the confusion, Herbert Aptheker, the Communist historian, made an excellent presentation, laying out the relationship between racism today and the potential of fascism tomorrow. For me, it confirmed the correctness of my decision to join the Communist Party almost a year ago to that date. With all its obvious flaws, the conference was nevertheless one of the most important political events of the season. It established the basis for breaking out of the narrow nationalism so prevalent in the Black Liberation Movement and pointed the way for alliances between people of color and white people around issues that involved us all.

To read about everything that happened to the Panthers is breathtaking:

Repression was on the rise throughout the country. The worst victims of judicial frame-ups and police violence were members of the Black Panther Party. Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins had been indicted in New Haven. Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were murdered by Chicago policemen as they slept in their beds. And in Los Angeles, the Black Panther Party headquarters was raided by the Los Angeles Police Department and their special tactical squad, with the National Guard and the Army on alert. I witnessed this raid firsthand and, along with my comrades, helped to organize resistance within the Black community. Our success in pulling together a grassroots challenge to this repression put the city and state government on the defensive for a short time. It also doubtlessly increased their desire to eliminate all of us.

And this was before the assassination campaign that was initiated by Chicago police and the FBI.

In the end, this book is a remarkable and brilliant testament of a giving, kind, and relentless activist. Angela Davis continues to write books with trademark clarity. This book should be read by all.

Angela Davis’s ‘An Autobiography’ is published by Haymarket Books on 2021-10-19.