Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

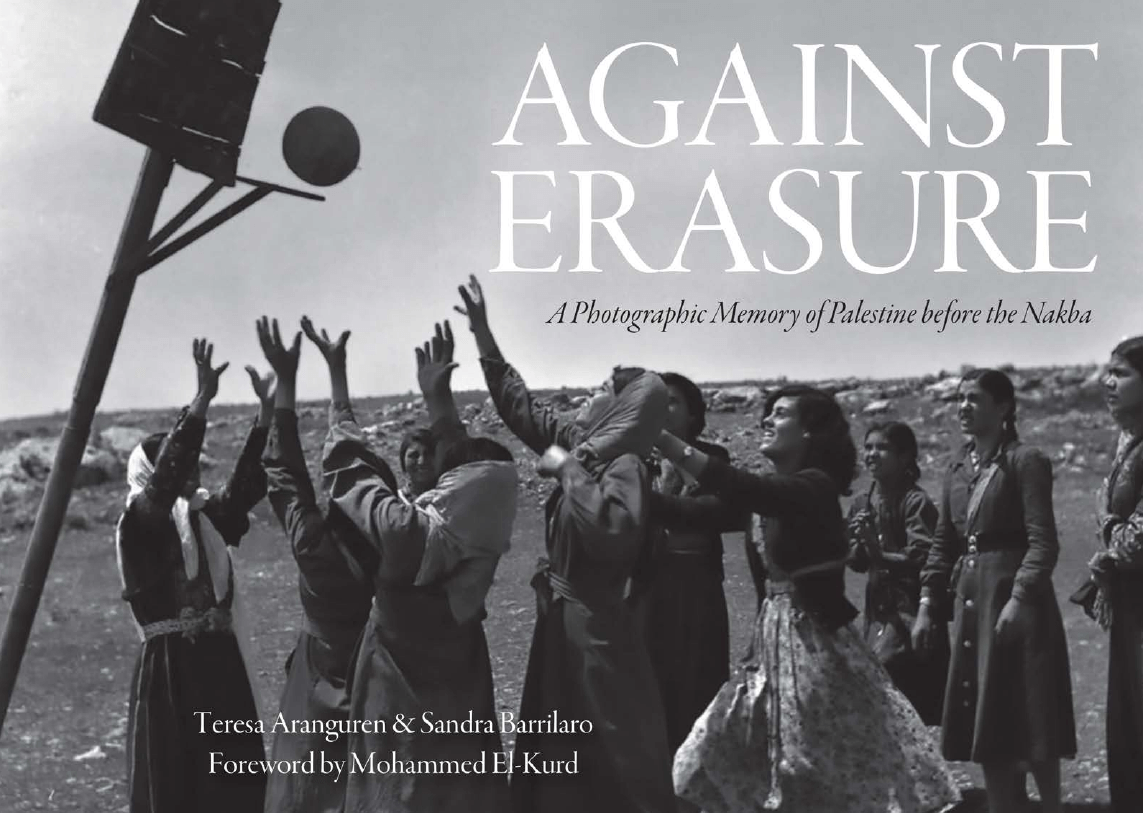

Before Palestine became a name synonymous with conflict, or indeed one antonymous to the existence of the State of Israel, it was simply Palestine. Obvious as this may be, it is often forgotten. And that forgetting did not happen by chance. The name Palestine, which appeared in Egyptian inscriptions in the twelfth century BC, has been the name that over the centuries has been designated in geographical, historical, cultural, sociological, demographic, administrative, and political terms to the area. Between the Mediterranean and the Jordan, between the mountains north of Galilee and the Sinai Desert, the territory that in the Roman Empire was called Palestine is identified with that which in the nineteenth century, with the same name, was part of the Syrian province of the Ottoman Empire. A land as old as the history of mankind, replete with religious and historical connotations for East and West, Palestine above all is the land in which the Palestinians lived.

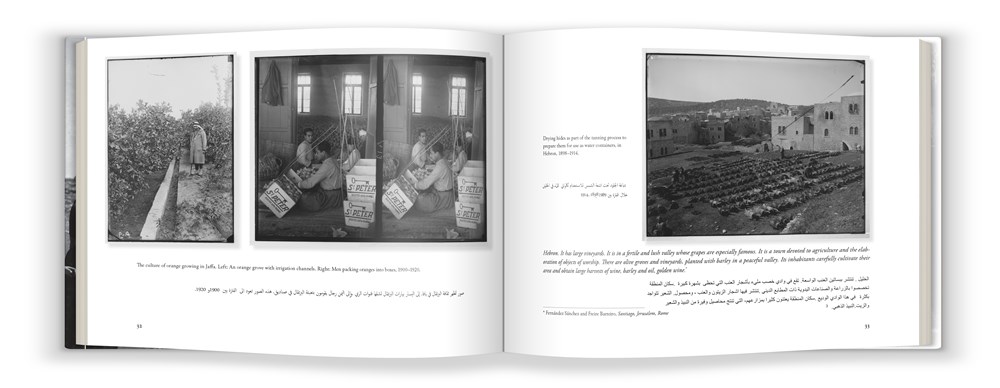

To me, this book paints beautiful imagery of life in Palestine before and during the time when a zionist government started trying to tear the land to shreds. Palestinians lived their lives: families and different types of organisations smile at the camera, cultivate land, play football, sell stuff. They lived.

Then, there’s the Balfour Declaration:

In a letter of November 1917 to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, Sir Arthur James Balfour, Her Majesty’s Foreign Minister, pledged Great Britain’s support for the creation of a National Home for the Jewish People in Palestine. The famous Balfour Declaration was in principle a simple confidential letter with no legal validity. But legality meant nothing when it came to colonial interests. An illustration of this imperialist cynicism is found in the following paragraph of the memorandum written by Lord Balfour to his government in 1919: ‘We do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country… The four Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.’

The book does a fine job in explaining the history of Palestine and Palestinian peoples, which is not only confined to muslims, arabs, or any faction by name; many people feel that they belong to Palestine in heart and soul, not least because they feel immense solidarity against the genocidal assault from the Israeli government, one that has continued for many decades.

Between 1917 and 1947, Palestine was held completely hostage to the maneuvers of British colonialism. In the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Great Britain promised the Zionist movement a Jewish National Home in Palestine. At that time, Jews represented 6 percent of the population and owned barely 1 percent of the land. During the twenty-six-year period of the British Mandate (1922–1948), successive waves of Zionist immigrants transformed the demographic composition of Palestine, and by 1947, Jews formed 33 percent of the total population but still owned only 6.6 percent of the territory. British support of the Zionist movement was assured—a support, it must be stated, not driven by philanthropic motives. The postwar Middle East produced a consensus between the Zionist objective of colonizing Palestine and the British objective of securing a base of support in the vicinity of the Suez Canal. The Zionist project served the interests of British imperial strategy. However disastrous the role played by the British would prove for the Palestinian people, it should not obscure the role of the Zionist movement, which, since its first congress in Basel in 1897, had decided to establish a Jewish state in Palestine—which clearly and emphatically meant the “de-Arabization” of Palestine or, in other words, the “invisibilization” of its people to facilitate the Judaization of the country. The early twentieth century propaganda slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land” represents the hard nucleus of Zionist ideology. Chaim Weizmann, one of the movement’s leaders, candidly acknowledged the Zionist texts as containing almost no mention of the Arabs. But the Palestinians did exist, and they lived in their land and defended it, as demonstrated by the numerous revolts against the British politics of complicity with the Zionist project that marked the years of the Mandate between the two world wars. Indeed, Ben-Gurion, the future president of Israel, made this revealing statement: “Let us not ignore the truth among ourselves … politically we are the aggressors and they defend themselves… The country is theirs, because they inhabit it, whereas we want to come here and settle down, and in their view we want to take away from them their country.”

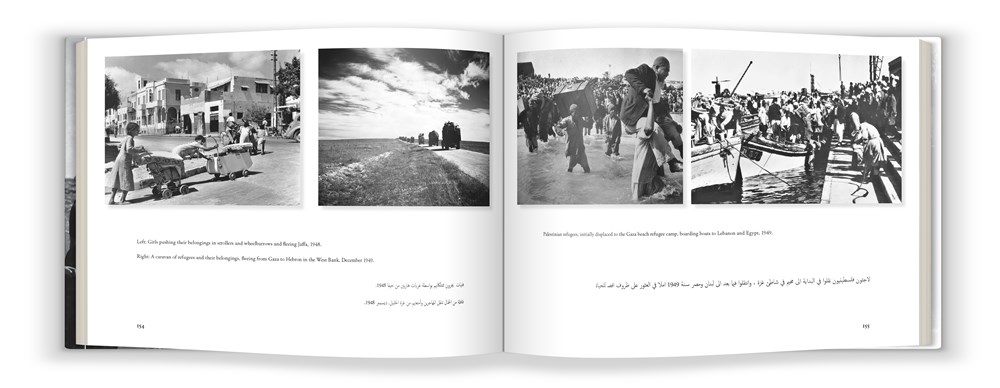

In 1948 came the Nakba, the violent displacement of Palestinians and occupation of their land. It led to the forced exile of two thirds of the arab population of Palestine.

Following the passage of the UN resolution on November 29, 1947, the Zionist leaders launched a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing. The objective was to conquer “the maximum territory with the minimum population.” On March 10, 1948, the Zionist leadership led by Ben-Gurion gave the green light to the so-called Plan Dalet, which established the military strategy to rid the territory of its Arab population. In his book The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Israeli historian Ilan Pappé describes part of this master plan:

These operations can be carried out in the following manner: either by destroying villages (by setting fire to them, by blowing them up, and by planting mines in their debris) and especially of those population centers which are difficult to control continuously; or by mounting combing and control operations according to the following guidelines: encirclement of the villages, conducting a search inside them. In case of resistance, the armed forces must be wiped out and the population expelled outside the borders of the state.

Palestinian scholar and writer Walid Khalidi puts the figure at 418 Palestinian towns destroyed in the months before and after the creation of the State of Israel, while other sources estimate the number of Palestinian villages destroyed or transformed into kibbutzim, nahalim, or moshavim at 531. Between December 1947 and June 1948, almost two-thirds of the Palestinian people (731,000) were forcibly exiled.

This is a remarkable book among many of its kind, because of how the photographs simply and extremely effectively show human life before and in the middle of extreme attempts to simply eradicate a people from existence.

Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba is published by Haymarket Books on 2024-02-20.