Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

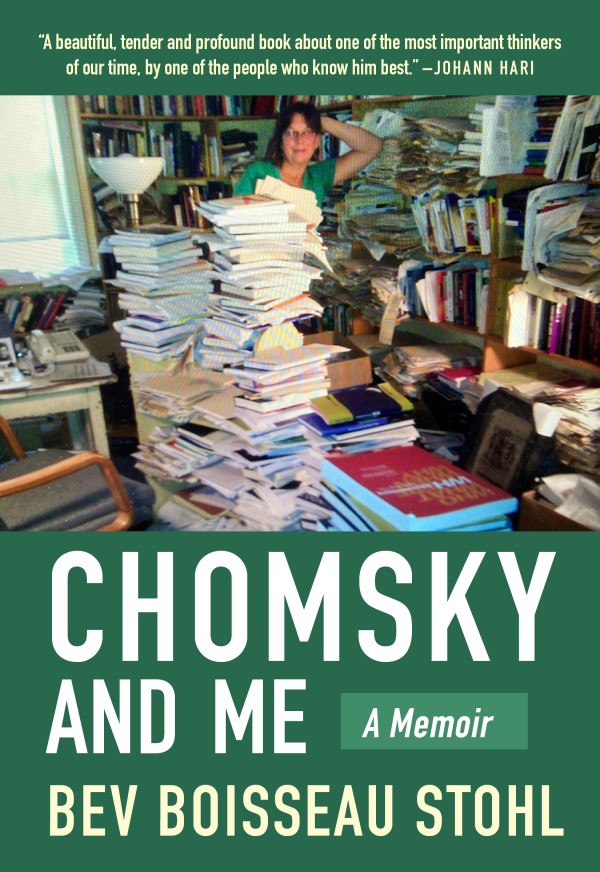

For years, I eagerly waited this book to be published. Before it came out, I read Bev Stohl’s Stata Confusion, for a few years and was entertained by her stories about Noam Chomsky, her employer for 24 years until 2017, which is when he moved from Massachusetts to Arizona.

People asked me what it was like to work for Noam Chomsky. When I answered—saying he was a brilliant man, a genius, and an altruistic superhero—I saw the pedestal I had placed him on. I also noticed that I was measuring my worth mostly through the lens of who I was in his world, knowing that the pedestal I was on by association with him would in time collapse under me.

This book is written by a level-headed person with a shining sense of humour, someone who clearly loves Noam Chomsky but was not a fan before she met him. She’d not read Manufacturing Consent, something that made her ‘pass the test’ with Morris Halle, Chomsky’s longtime colleague and friend at MIT, who interviewed her for the position. Then, she met her new boss.

He held a briefcase in each hand—one heavy blue canvas, the other worn brown leather with the letters “NC” stamped in faded gold at the top—a good indication that this was my new boss. Sighing, he pulled a thick pile of papers out of the brown briefcase. “Backup,” he said, plunking them onto my desk, expecting me to understand. He looked up, appearing to notice that I was not his usual assistant, and introduced himself simply as “Noam.” I stood to shake his outstretched hand and watched him do something I would see a thousand times more: a subtle shift as Noam Chomsky’s mind joined his body from a faraway place and he arrived in full. “Hi, Professor Chomsky. I’m Bev Stohl. It must be strange to meet your new assistant for the first time,” I said, referring, I guess, to his not having interviewed me. It was too late to start over, and fainting would have made a bad first impression, so I stood there, looking at him. To my relief, he spoke again. “You can call me Noam. I have full confidence in Jamie and Morris. If they chose you for the job, I’m sure we’ll make a great team.” He tilted his head upward, looking good-humored and delighted when he said this. His wide smile emanated from his mouth to his eyes, multidimensional behind thick lenses. When he rifled through the mail he had plucked from his box, I watched his face change again, a lifted eyebrow, a sideways tilt of his head, a furrowing of his brow. Then he disappeared into his office. Meeting him for the first time, I thought, “Maybe I won’t have to be shipped back home. And what’s the big deal about working for Noam Chomsky?”

Chomsky may be one of the most quoted and now-living people on Earth. He’s also been extremely approachable. For decades, he’s spent time revolutionising entire scientific fields, perhaps mainly linguistics, computer science, political criticism, and philosophy of sorts. He’s often spent a few hours every day (except during summers) with answering correspondence from most people who have written to him. Over decades, he’s engaged in public speaking and been arrested multiple times for speaking publicly against authority. He’s written over 150 books. He’s ludicrously been branded an antisemite for defending the right to free speech1.

It’s easy to spot fans of Chomsky’s; I should know: I’ve not been a fan, but I’ve come dangerously close to, in my younger years, feeling that Chomsky was an all-seeing being and source of Truth more than simply being a scholarly person. In any case, this book would not be very interesting if it had been written by myself, but it is funny, engaging, and filled with love, as it’s written by Bev Stohl.

To read about how her world expanded by interacting with Chomsky is enlightening.

Navigating my strange new world, the phrase manufacturing consent continued to surface in different contexts, which confused me. I saw it was the title of a book, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, written by Noam and Ed Herman in 1988, and that filmmakers Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonik produced the documentary Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, four years later. In the 1980s, Daniel Ellsberg of Pentagon Papers fame had opened my eyes at an MIT lecture by pointing to covert crimes carried out by the US. For instance, weapons supplied by the US had killed American troops, and anyone leaving the US had an FBI file. Watching the documentary, I began to understand why people had such admiration for Chomsky’s dedication to peace and social justice. I felt my own twinge of hero worship as my knowledge of world politics grew to include conflicts and people I had known little about, like public intellectuals Howard Zinn, Palestinian professor Edward Said, and Israeli professor and Holocaust survivor Israel Shahak. A year into my initiation, I wondered at the need for a police detail for a Chomsky-Said-Shahak event on Jewish fundamentalism. I knew very little then about the Israel-Palestine conflict, the apparent reason behind the police presence.

Yes, police presence. Chomsky has both benefited from the U. S. right to free speech and been extremely critical about matters such as the death penalty—’a crime’, in his words—and capitalism, which means he’s been a low-key threat to the ruling class. I say low-key because Chomsky has not been invited into popular media2 despite of his achievements.

There are many stories of how Chomsky has felt for peoples3 and acted because of what has happened or was about to happen. Stohl tells a story of how he briefly warned her to forward any suspicious-looking mail to campus police. This was during Ted Kaczynski’s time, the Unabomber. After Kaczynski was caught, some of Chomsky’s writing was found taped to his cabin walls.

A decade later, a friend of Kaczynski’s activist mother asked Noam to call her on her eighty-ninth birthday. During the call, I was witness to Noam’s empathy and kindness.

Stohl tells warm and kind stories from everyday life as Chomsky’s assistant, and they glow with humanity and humanism. It’s not strange to know that Chomsky had a big poster of Bertrand Russell taped to his office wall at MIT4.

Years later, I asked a few ex-students what their meetings with Noam had been like. A reply from Raj Singh, associate professor of cognitive science at Carleton University, is typical: The way I remember [this one meeting], he was commenting on a draft of a paper I was working on that would become part of my dissertation. It felt to me like each time he turned a page he had a new barrage of criticisms—flaws in the logic, counterexamples, obvious (to a mind like his) ways I could have stated things better … I was trembling, probably sweating, embarrassed that I had wasted his time yet deeply honored and humbled that I was sitting there getting the beating of my life. When it finally came to an end, he looked at me with that warm, grandfatherly smile and said something like, “Looks pretty good to me.” I am sure he meant it. The paper later appeared in Natural Language Semantics.

Then, there’s the fun that seeps through the book.

Work was busy. Pearl Jam’s graphic designer asked permission to print Noam’s likeness on a skateboard for a series of promotional decks they would name “American Heroes.” Noam had replied: “Don’t want to sound as though I’m from some newly contacted tribe in the Amazon jungle, but … I don’t know what skateboard decks are.” I explained to him that Pearl Jam was an intelligent political band, and that a deck, which became a skateboard when wheels were added, would impress Alaitz, his oldest grandson. Jay loved Pearl Jam and urged me to stress their political significance to Noam. When I did, Noam recalled an article he’d written on Cuba’s sovereignty for Pearl Jam’s “The Manual For Free Living” newsletter way back. This proved once again that he knew, and remembered, more than he let on. I gave them the OK for the decks. A while later a package arrived. I was ecstatic as I unboxed t-shirts, CDs, and three decks.

Naturally, the extreme polarities of the funny and the serious intermingle in single book paragraphs.

We’d been together for eleven years, long enough for me to develop a sixth sense about him, so when the phone rang on his first day at Stata, I knew he was lost. “Noam?” “Uh, Bev …” “You’re lost, aren’t you?” His trademark sigh blew through my end of the receiver. “Yes, how did you guess? I’m calling from a library area on the eighth floor …” I heard voices, then a brief silence. “I’m in CSAIL, in the Gates Tower. Your friend Maria says hi.” “Well, you’re in the right building,” I reassured him, imagining that he missed the dilapidated, asbestos-laden Building 20, which reflected life’s imperfections and was more fitting with his politics and worldview. He had joked that MIT’s administration kept its rabble-rousing professors hidden away there. “You took the wrong set of elevators. Go back down to the first floor, to the open area—this is Student Street …” Imagining him waiting for a key piece of information, his brows knitting as I meandered toward my point, I reined in my tendency to wordiness. “Return to the first floor. I’ll find you.” I rushed to the elevator and pressed “1.” For months I’d organized our new space, refilling floor-to-ceiling shelves with his books by Jacobson, Wittgenstein, Marx. Copies of the books he had authored and their translations, arranged chronologically, filled walls of similar bookcases near Glenn’s desk. Noam’s master’s thesis, “Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew,” was the cornerstone on the top shelf on the lefthand side of the room. Hegemony or Survival, his newest book, was shelved on the other side of the room. His published books by my count neared ninety. Six long empty shelves beckoned future crises, future truths.

It’s hard to not be gobsmacked by Chomsky’s mental faculties.

I handed Noam a library book, which he opened and leafed through with one hand, rolling a piece of scrap paper between the thumb and forefinger of his other, visually scanning a page, flipping ahead, scanning. When he handed it back to me I was confused and asked if it was the wrong book. “No, it’s the right book. I got the information I needed. You can send it back.” He hadn’t written anything down.

Reading is one thing, but putting things into action is another.

“Do you know the real story behind July Fourth? Maybe you can bring home the article I wrote, called ‘A Few Words on Independence Day.’ I fished a copy out of the file cabinet. That night, I barely got past the start: “Independence Day was designed by the first state propaganda agency, Woodrow Wilson’s Committee on Public Information (CPI), created during World War I to whip a pacifist country into anti-German frenzy …”

Stohl’s words on Carol Chomsky, Noam Chomsky’s first wife, and her terminal cancer, is absolutely shattering. I won’t quote the material here but it’s absolutely breathtakingly sad because of what happened and beautiful to see Noam Chomsky’s love for his wife.

Soon after, I saw him with a big sticky cinnamon roll and asked what it was. He replied, “Breakfast.” From then on I brought him lunch from home. I never thought twice about it until I handed him a dish of chicken and vegetables in front of a friend. He had put his arm around me and said, “I have a few guardian angels keeping me going.” I felt a seismic shift in my heart whenever he revealed a fondness and gratitude toward me. I felt the same toward him.

Here’s a quote from Stohl’s Reddit AMA that she did in December of 2022:

I write alot in my book about “bursting into tears” - this was impossible not to do in a number of circumstances. You’ve choked me up here. In the book there is a scene of us sitting together watching Michel Gondry’s “Is the Man who is Tall Happy” at an MIT theater. He always had a cough, and during the movie I touched his hand to pass him a lozenge. I hadn’t realized how emotional he felt during the scene that was playing with Carol, his first wife, until I nudged his hand passing the lozenge, and he squeezed my hand for a good while.

There’s so many lovely stories told in this book. Of humans connecting. On why Chomsky isn’t angered by angry people who emailed him. Trips to Australia and Italy. Stohl, a comedian at heart, tells things from a weighed professional’s point of view but never wavers from the personal, from what gives tales around and about academia a…sparkle. All of this while handling Chomsky’s schedule and…everything. Stohl truly is a lovely storyteller. Dialogue and summation is her forté; don’t expect long story arcs in this book. She paints a lovely picture by using little strokes, and it’s lovely to read the results: you see a long way ahead.

Noam Chomsky was voted the world’s top public intellectual in 2005 in Great Britain and has been compared to our greatest thinkers— Plato, Aristotle, Freud, Einstein. I tried to keep this in mind as I watched what he did next. He lifted the large mug next to the coffee maker, filled it to the top with water, and poured it into the Keurig. “I’m not sure whether I already filled this,” he said. Then he popped the pod into its slot, waited for the water to disappear, and closed the lid. So far, so good. Next, he pulled a smaller mug from the cabinet and set it under the spout. Laura put her glass down. “Noam, stop! I know what’s happening here,” she said. Noam looked puzzled. “What did I do wrong? I did it exactly as you said.” He loved to watch other people problem-solve, particularly because of his conviction that technical problems have no logical solutions. “You’ve been adding water from a larger mug, so that amount of water is pouring through the pod into the smaller mug, and the excess coffee will overflow into the lower receptacle. If you continue to put in more water than the receiving mug can hold, the extra coffee will overflow from the receptacle onto your counter. “And eventually flood your house,” I deadpanned. “So the mug I pour the water from and the mug I drink from should be the same?” “Or at least the same size. Filling the reservoir once and making your coffee right away will also help,” Laura said, closing her argument with a pull of scotch. Looking at Laura, he raised his own glass to his lips and drank. “Surely there’s protein in scotch!” His eidetic memory didn’t extend to protein or a coffee mug’s size, but only because they were the least of his worries.

This is a thoughtfully written book. Stohl is very funny, viscerally warming, and candid. This makes for pictures of more than one person, and ultimately, about ourselves. The book is a reminder that nobody should put people on pedestals (which goes into Chomsky’s sentiment that anarchy is a human tendency along with his deeply underlying humanistic ideas on empathy and love) and apply critical thinking everywhere, or we betray ourselves and others.

“Faurisson Affair.” Wikipedia, May 9, 2024. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Faurisson_affair&oldid=1222991542. ↩

A side note: one of my favourite popular-media interviews with Chomsky was with William F. Buckley Jr., recorded and broadcast in 1969. Stohl’s words about this: ‘The death of author and intellectual William F. Buckley Jr. in early 2008 pulled a YouTube video of a contentious 1969 interview to the forefront of a surge of emails to Noam. I knew of Noam’s appearance on Buckley’s acclaimed show, Firing Line, but only now, nearly forty years later, did I learn that Noam had pissed off Buckley by swerving from his host’s script, and by repeating truths contradicting Buckley’s assertions and making him explain himself. When Buckley claimed that communist insurgencies existed prior to the Nazis, Noam countered that there were communist resistance bands fighting against the Nazis, but no insurgencies. The video shows Noam’s insistent, cool demeanor, as his frustrated host throws out snarky remarks like a heckled comedian, demonstrating to Buckley and his audience that Noam was a force to be reckoned with.’ The video: Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr.: Vietnam and the Intellectuals, 1969. Accessed June 15, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DvmLMUfGss. ↩

One of my personal favourite stories: Branfman, Fred. “When Chomsky Wept.” Salon. Last modified June 17, 2012. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.salon.com/2012/06/17/when_chomsky_wept/. Stohl comments on the article in the book: ‘People always asked me—and him—where his compassion came from. He never wanted anything to be about himself, so didn’t reply. Early on, he was profoundly affected by his time in Laos, a story Fred Branfman told beautifully in a 2012 Salon article, “When Chomsky Wept.” Following a flight cancellation in February 1970, Noam hopped onto the back of Fred’s motorcycle and learned more about the secret US war there. Fred hoped having Chomsky join him might make the bombings known to the world and contribute to ending the war: [W]hat most struck me by far was what occurred when we traveled out to a camp that housed refugees from the Plain of Jars. I had taken dozens of journalists and other folks out to the camps at that point, and found that almost all were emotionally distanced from the refugees’ suffering … [T]he journalists listened politely, asked questions, took notes and then went back to their hotels to file their stories. They showed little emotion. … Our talks in the car back to their hotels usually concerned either dinner that night or the next day’s events. I was thus stunned when, as I was translating Noam’s questions and the refugees’ answers, I suddenly saw him break down and begin weeping. … Noam himself had seemed so intellectual to me, to so live in a world of ideas, words and concepts, had so rarely expressed any feelings about anything. I realized at that moment that I was seeing into his soul. And the visual image of him weeping in that camp has stayed with me ever since. When I think of Noam this is what I see.’ ↩

From Stohl’s Reddit AMA in December 2022: ‘The Bertrand Russell poster became the backdrop for most photos taken in Noam’s office. I never asked how it got to be there in the first place, but Noam told me he admired Russell for the most part (Russell was a known womanizer, but other than that) because of how he lived his life. The quote accompanying the poster read: “Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind”.’ ↩