Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

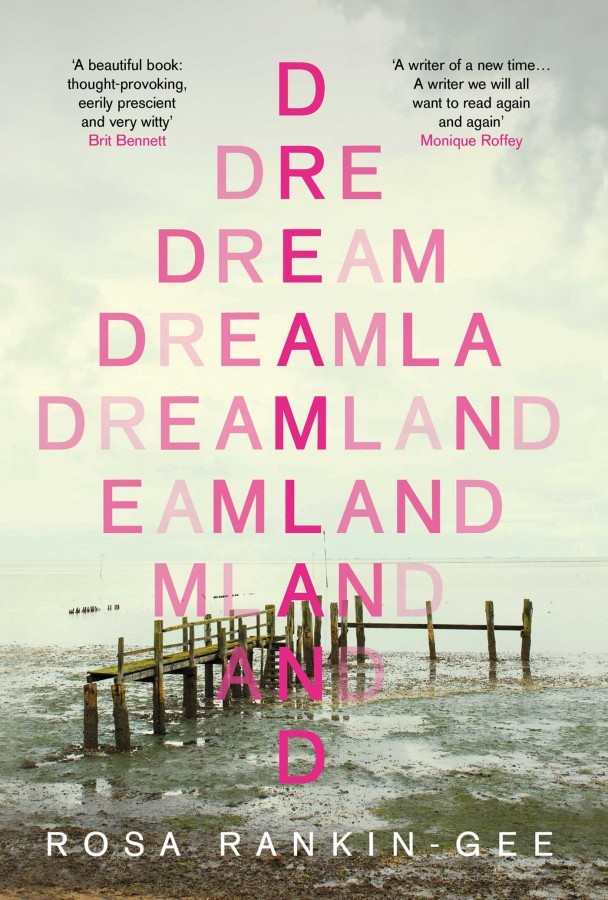

I’ve reviewed Rankin-Gee’s Dreamland here.

Here are some memorable excerpts that I’ve pulled from the book.

We had different dads, so he was my half-brother actually, though it never felt like that. The way she always said it, was that his dad was stupid and mine was Swedish – though I came out alright.

She said London was too expensive to be the future. She said it was a fourth world country now. A hotbed, a bomb waiting to go off. That, and an island for rich Russians. She told us she’d always believed in the power of a clean start. ‘Look at all this,’ she said pointing around the room, then she put her fingers over my eyelids, heavy, and held them there, and said, ‘Pfff,’ the sound of a file deleting on her old laptop, ‘just like that, forget it. This is when life begins. From right now. No more waiting.’

‘My future breadwinner,’ she said, grabbing his head and kissing it before he could lurch away. ‘Didn’t pay for much, actually. When I was doing the art school thing, I once didn’t pay rent for six months! My Nan Goldin days. The Goldin Girls.’ She laughed, and knocked over her beer but managed to grab it before she spilled any.

Ma got a job at a pub called The Chipped Pearl, which had a sign above the door that said its chips were famous. She brought home the menu to show us. ‘Look, peanut,’ she said to me. ‘‘‘Our Famous Chips, served with our Famous Gravy.” It’s basically a pub for celebs.’

We started off by being rude to each other. Davey taught me that. He said that being polite didn’t really get you anywhere, particularly round here. ‘Being a pussy is for gays,’ he said. ‘Fact.’

Ma sent me to the same school as the other kids from the pub. Tracey Emin Academy, or TEA, though everyone called it Tracey’s. There were posters of her work in clip frames. Neon writing, blurred ink. She Lay Down Deep Beneath The Sea I Followed You To The Sun. Tracey on a horse, Tracey dancing. Tracey writing her name on the beach. I could spend ages looking at them.

One day that summer, when there was a strong enough breeze to push the worst of the heat away, Liam said we should hit the town. Maybe it’s just the difference to now, but it seemed there were so many people, like the whole world was out. Davey was up on a roof passing tiles up to his Uncle Trevor, and we saw some of Liam’s friends, too – the smiley one with the bleach-white teeth, and the one with the missing thumb Ma always said was sexy. JD held my hand on one side and Ma on the other, and Liam played on my head like a bongo drum from behind and it felt nice to be surrounded like that.

She told us that when she was young, you could plot the economy on the train tracks. Every percentage point employment went down, the more jumpers. ‘It’s all connected,’ she said.

Around that time, Davey brought his Uncle Trevor’s razor to class. He gave the two of us tattoos, matching triangles on the backs of our hands. There was more blood than ink, and the lines weren’t straight. He said we were going to stick together no matter what, and he spat into his palm to shake on it, this loose ball of saliva.

If JD was a pretty boy, this guy was an animal. Handsome, but like a jaguar or a lion – there was something big cat about his face. He moved his mouth around like he was getting something out of his teeth and was about to spit.

‘Did you see his arms?’ Ma said to me, pulling me away into the kitchen. ‘No,’ I said. I had. They were huge. ‘What about them?’ ‘Don’t look at them,’ she said. She spread some margarine so thick you couldn’t see the bread any more, and leaned in. ‘Track marks. It’s like a fucking terminus on there.’

I don’t know why the bruises made us all start. I sometimes think that there’s nothing childish about being a child. The opposite, almost. My first time was okay. He was only twelve or thirteen too. It was hands and pushing more than anything, no bigger than a finger anyway, this empty, soft thing. I remember the bed more than anything, the mattress looked like a big black bite had been taken out of it, a fire from a fallen cigarette. When we came out of his house, there was a group of older teenagers sitting out nearby. ‘You lot have started then. Fucking bait, bruv.’ They all shook the boy’s hand, that handshake where you bring it in to touch each other’s back. ‘Nothing else to do round here, is there?’ They looked at me. ‘No one else to do.’ After a few months my body had greenish thumbprints all over it. When Ma asked me what was going on, I told her we were all fighting, but for fun. Later, when I came back with a long red scratch across my neck, she threw an ice cube across the room at me. ‘Jesus,’ she said. ‘Isn’t there enough bad going on?’

The first time he hit her, I remember the blood coming from her eye, but maybe the blood had been on her hand and she moved it up by covering her face. After he’d gone, even though the networks were pretty much gone by then, she made me go to someone’s house to charge her phone, and then kept on checking the sound was on, in case he called her. He came back a couple of days later with flowers, and a pack of tissues. ‘Soft,’ he said, as if you could buy hard ones. ‘I am sorry though,’ he said after that. ‘I am sorry. It’s not me. It’s a different part of me.’ He looked at her. He looked at me.

‘Is that the Turner?’ you said, pointing to the tall concrete body of the art gallery, the sea-smashed windows. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Mostly a shooting range now.’ ‘For guns?’ you said. I looked at you. ‘Do you have a gun?’ ‘Nah.’ I slapped my wrist. ‘Needles.’

‘I nearly got eaten by a dog. Honestly, it was the size of an elephant.’ ‘I feel like you might be going to all the wrong places.’ ‘You going to show me around, then?’ ‘Too busy. I already have a job, thanks.’ ‘What do you do?’ ‘I’m a thief.’ ‘Nice,’ you said. ‘I’ll watch my pockets.’ ‘Anyway, there isn’t anywhere to go. And I don’t know you.’

There were so many seagulls that day. Huge fat ones, bald bellies covered in scars. About twenty of them chattered in the close sky above us. Sometimes they kind of looked like fighter planes, dancing in a club, drunk.

There was a guy called Serb who parked his van in different places each day – Yoakley Square, Windmill Gardens – but it was always easy enough to find him. A smell of fat in the air, and a little dingly tune every hour. He kept bags of pre-cut chips in the fridge not the freezer so they were quicker to cook, and he turned the oil off in between customers, but somehow his chips were the best. He kept his mayo in the sun, the vinegar was strong enough to feel like it stripped your whole nose, and every now and then, he threw a chip to the seagulls as an offering.

When I got round the corner, I stopped and waited. I thought about what it had been like to find your skin under your clothes. Cool and hot, how soft it was. How quickly my hands got used to you, the sound you made when you touched me for the first time. Fuck, I thought again. Fuck. All I could think of after that was a trigger. Again and again, between my legs, I felt the hammer of a gun cocking back.

You moved in your wandering way, touching things. A finger over the fat-thin pregnant belly of an ivory statue.A short little trill on the out-of-tune black notes of a piano. You went into a new room and tiptoed to see the highest shelf of an open cabinet.

I stayed there for enough time that it felt like all the time and also no time at all. No push. Slick, snug, a mouth around my fingers.

‘Don’t be a little bitch.’ ‘Stop calling me little.’

There were LandSave beermats along the length of the bar. Davey had scratched half the letters off his, so it said ‘d ave’.

He said some other things, then his hands let go of me, both at the same time. I stumbled back, and my back slid down against the wall. He walked out. I sat down on the floor in the small hot room after he left. Kole had told me if I touched you again he’d crush my hands. Make them bones of yours dust, he’d said. See how she likes you then. I brought my hands to my chest, curled around them, curled up tighter. I coughed, then I couldn’t stop coughing, and when I looked at my hands, there was blood in my palms, a bright spray of it.