Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

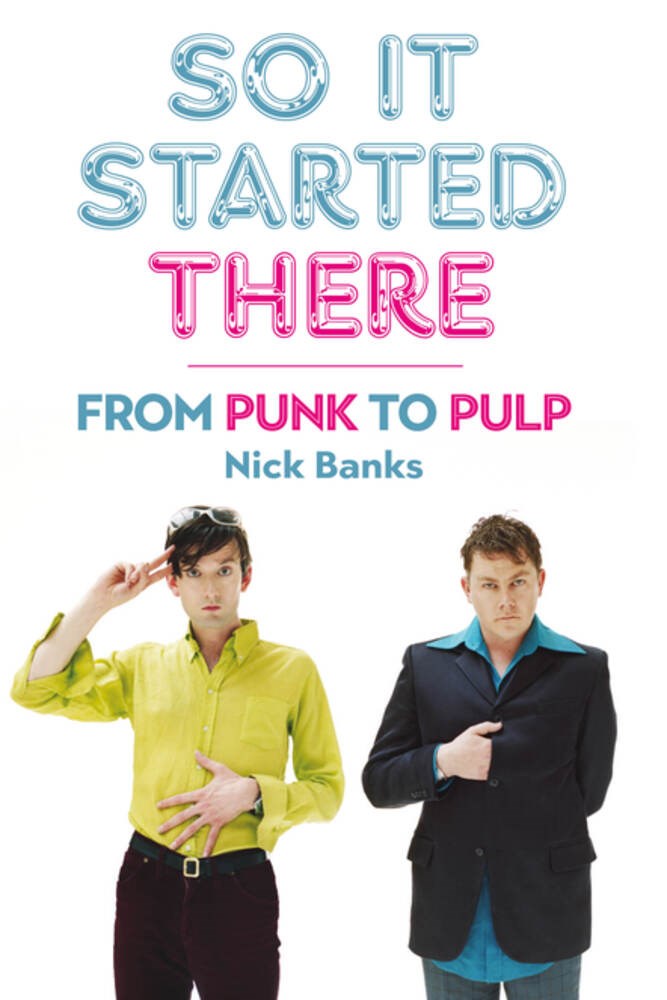

The introduction by Richard Hawley, guitarist extraordinaire and childhood friend of Nick Banks, the author, says a lot in his introduction:

I was going to talk about what a brilliantly gifted drummer Nick is, but that would be equally far-fetched. He is by his own admission an average musician, his timing a little questionable … I believe I may have coined the phrase ‘In and out of time like Dr Who’. However, given the right band he is irreplaceable.

Hawley’s observation also applies to Banks’s writing. Although there’s quite a lot of repetition in the book1 and it’s a kind bit of shambles, it’s at times funny, self-deprecating, and the first third is a hoot as far as Banks’s family are concerned. Any person will relate to some of his familiar words:

As the birthday was on the horizon my eyes were peeled for a suitable ‘cool as’ skateboard to ask for. Got to be a dead cert for a birthday present. Dutifully, the ‘Alley Cat’ skateboard, resplendent in black and yellow, was selected at the toy/sports shop. ‘That’s the one I want for me birthday, Mum,’ I said, hopefully. Come the day, the wrapping was torn off to reveal not the black-and-yellow Alley Cat but a very much inferior ‘Flying Pigeon’, plywood ‘deck’ with rubber roller skate wheels screwed underneath – definitely not the state-of-the-art bright yellow polyurethane wheels of the Alley Cat I was so desperate for. ‘It’s a skateboard, isn’t it?’ I was told. Technically, yes, I suppose. But so far from what I needed. Almost certainly off Rotherham market. Mum’s oft-quoted phrase on these matters was: ‘Well. They’re all made int’ same factory. They just stick a different label on ’em – they’re all the same!’ No they were not.

Many paragraphs are single stories. I’m anti-nationalist, but I do feel that some English autobiographies are far less filler than killer, especially in comparison with American autobiographies. I love the English terseness.

The human parts of the book are the best bits, I think.

‘I’ll play guitar,’ said John. ‘What you wanna play?’ ‘Err … I’ll play bass!’ And there you go, a new band is born. It’s that easy. It didn’t matter that we had no instruments or any idea how to play instruments. Just the conceptual leap was enough. If you said you were a band you were.

It’s sweet to know Banks was a self-proclaimed Pulp fan before joining the band. He bought singles and attended gigs, before he found a note somewhere saying they were looking for a new drummer.

Then, the long wait started for Pulp.

They had some success in recording a session with John Peel, that beacon of light. Then, not much happened, apart from people leaving and joining the band, and immense album troubles. The troubles only grew larger once Pulp started getting more well-known.

Jarvis could write a tune. Jarvis could mesmerise an audience. Jarvis was unafraid to go out on a limb. Jarvis was a walking music encyclopaedia. Jarvis was, and still is, funny as. Trouble is, Jarvis also doesn’t have an ‘off’ switch. He’s in a constant whirl of daft voices and acting out scenarios that only he can see in his head. Which can all be incredibly hilarious, and yet irritating … frequently all at the same time. Jarvis lives by Jarvis time, and that ‘time’ is not necessarily the same as for us mere mortals. Don’t expect punctuality.

Jarvis is a keen ‘collector’ – of any old tat. To the untrained eye it might look like hoarding. Needless, to say he has a lot of stuff. So, on the moving-in day Jarvis appears with Kirky’s Transit absolutely filled beyond the brim with all manner of trash – sorry, my mistake – carefully curated curios and antiques. We all chip in and start helping unload, only for another car to pull up at the kerb. ‘That’s my driving instructor,’ says Jarvis. ‘I’ve got a driving lesson booked.’ Jarvis promptly abandoned the unloading, jumped in the Ford Fiesta and kangaroo’d off down the road. ‘I’ve got a band to shift and a gig to do in about 20 minutes,’ said Kirky. So, it was left to the rest of us – actually, mainly me – to empty the van and fill Jarvis’s room with his ‘stuff’. This included: Joe 90 annuals (many) Seventies ceramics Plastic fruit Millions of records Bin liners full of jumble sale clothes (far fewer charity shops back then) Two life-size cut-outs of cartoon nurses from the fifties Dressmaker’s mannequins, at least two This is just a sample of the torrents of ‘collectables’ we decanted. You could barely get in the room once everything was in it. Still, Jarvis brought yet another layer of odd to Burgoyne. Which was starting to feel more like a bit of a scene, I guess – well, at least to us, I suppose. There was always something going off, often creative, sometimes surreal.

Jarvis Cocker has written a book2 about things. Some of Banks’s notes bring more earthy tones to Cocker’s natural writing, which outshines Banks’s by miles. Still, this book is interesting, but ceases to be once Pulp have become famous.

The world does become different under the illusion that fame is.

Bizarrely, Russell took his young family for a break in Scarborough on the Yorkshire Riviera and one day noticed something odd going on down on the beach. Turns out it was Donald and a cut-out of Russ himself being photographed amid a herd of beach donkeys. Completely coincidental.

Some of the writing comes across as a bit harsh to me, especially in Banks’s view of people who liked Pulp. Example:

We had heard that the fans in Japan were something else. It was all true. They were waiting for us at the airport in Osaka and were omnipresent, hanging around in the hotel lobby waiting for a member of the band to appear so they could ply us with gifts, usually of the edible nature and all done with extreme politeness and a little giggle (they were almost exclusively girls). It was a bizarre notion to us as to why these kids would wait around all day just for a few seconds of contact, and we’d ask whether they hadn’t got better things to be doing … obviously not.

The notorious shit-on-Michael-Jackson move is mentioned:

On to the grand finale, which was Jacko receiving his faux award and trotting through ‘Earth Song’ – as I’ve said, we all found this deeply disturbing, but it was dear little Candida that was the spark to the flame. Jarvis was getting more and more riled up about Jackson and his guff and we noticed that to our right there was the gangway that led directly to the stage and it was unguarded. Opportunity was knocking. Doyle egged Jarv on by saying ‘You’ll never do anything about it!’, and the next thing, Jarvis, accompanied by Peter Mansell, was off across the gangway, stage bound. Manners got the fear just across the bridge and turned back, but Jarvis was not to know this and was off, cavorting around the stage, doing nothing more controversial than lifting his jumper and miming shitting on the Jacko acolytes in the front row. He then had to evade stage security – who were dressed as if from the Old Testament, of course – and make it back to the table. It really wasn’t that much of a protest. While he was doing all this we were stood on our chairs shouting, screaming and crying with laughter: ‘Go on, son!’ What would have happened if MJ was not 30 feet in the air atop a cherry picker machine? No one knows. The whole thing was over in a flash and it was amazing and everything bands should do when faced with utter po-faced pomposity. Jarvis flopped back in his chair rather wild-eyed and was immediately swamped with folk like Brian Eno slapping his back and saying well done, about time someone did something like that, and all that kind of stuff.

This is Hardcore did the band in somewhat, according to Cocker. Drugs, fame, the lot.

The truth was that Pulp had run out of steam. The labour pains of making Hardcore and We Love Life had taken their toll. We were knackered as a group: tired of each other and tired of just being Pulp. We had been in constant proximity for nigh on 12 years and, as happens with many groups, you just get a bit sick of the sight of each other. Well, in truth I wasn’t. I would’ve been happy for us to stay on the rock’n’roll hamster wheel – write new material, release records, play them live – but I could see that a breather was required. Big time. We would adjust to not being front and centre of the nation’s (quirky pop) mindset and would remain content to keep doing what we did best: incendiary live performances and interesting, slightly odd pop music. Alas, it wasn’t to be. Others had already started to map out their futures sans Pulp.

All in all, this book has steam and fun in its first third. The rest of it consists of fairly predictable going-through-the-motions writing about being in a successful band. I wish there’d been far more thought put into this project, as with, for example, Jarvis Cocker’s books or even Beastie Boys’ book3, not to mention the autobiography by Cosey Fanni Tutti4.

For example, we know Steve was to the club Shoom because it was mentioned twice. ↩

Cocker, Jarvis. Good Pop, Bad Pop. London: Vintage, 2023. ↩

Diamond, Michael, and Adam Horovitz. Beastie Boys Book. First edition. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2018. ↩

Cosey Fanni Tutti, Art Sex Music (London: Faber & Faber, 2018). ↩