Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

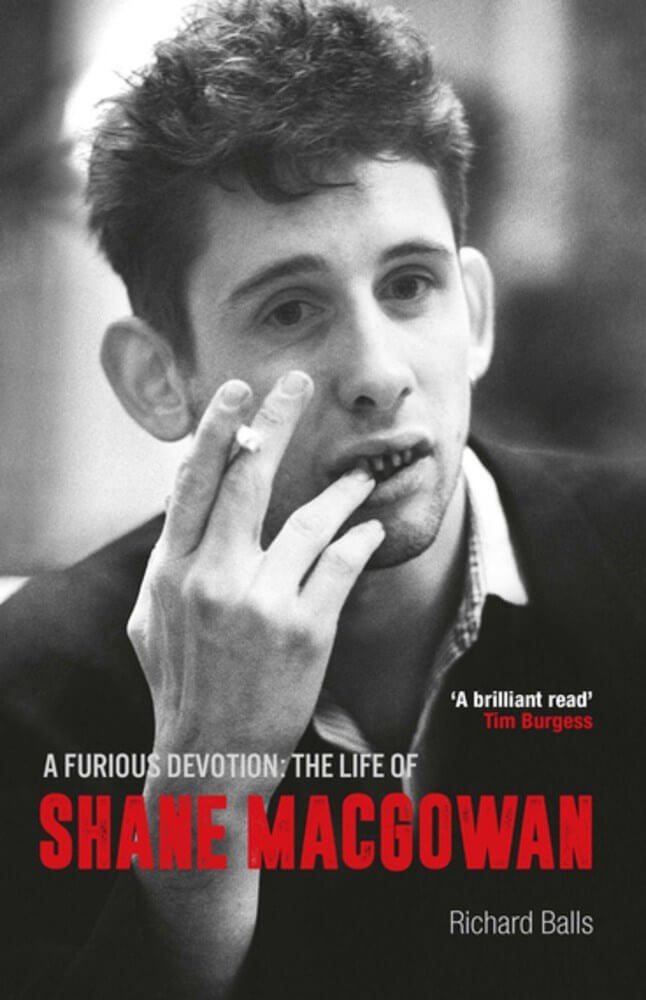

Shane McGowan was a supreme modern lyricist. Some of his songs are masterpieces. Others are piles of ish. He knew he was an addict. He grew up in a poor household. He abandoned his friends, his girlfriends, most people who depended on him. And he loved, he seems to have truly loved his wife until the day that he died.

Shane’s rambling recollections about the record label that took a chance on The Pogues are punctuated with his notorious snigger – ‘tsscchh’ – which sounds like someone gargling with gravel. At one point he falls asleep on the recorder and I have to gently prise it from under him.

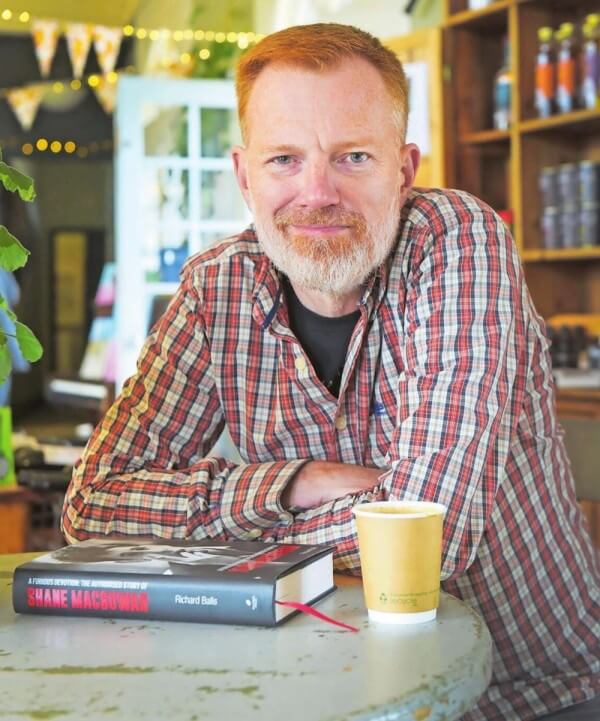

The author knew Shane McGowan. They spent much time together at the end of McGowan’s life. Through McGowan, the author got to know McGowan’s father, Maurice, and a lot of other people who were close to McGowan over the years.

Even though McGowan is known through UK press as a shambles, an alcoholic, a druggie with horrible teeth, the precursor to Pete Doherty, he was highly self-aware and, in some ways, beyond reproach. When he was 13 years old, one of his short stories won a prize in the Daily Mirror. He was interviewed. His favourite author was James Joyce and he enjoyed Jean-Paul Sartre and Thomas Mann.

He was Irish and lived in England. He made his way to England as a teenager, made up a London accent, and got deeply into punk and people and lust and love and formed a band. Then he formed another band, tthat was renamed The Pogues.

By the end of 1985, The Pogues were the darlings of the music press. Rum Sodomy & The Lash was voted number two in Melody Maker’s albums of the year and Shane named Chap of the Year. NME chose ‘A Pair Of Brown Eyes’ as the ninth best single and the album came eighteenth in its end-of-year list, and The Pogues also had no fewer than four songs in John Peel’s famous Festive 50.

Other artists, like Tom Waits, seemed to have adored The Pogues, not least for McGowan’s lyrics and song. He used an alcoholic’s way of slur-singing angelic lyrics that appeared lifted to the skies for the grace of God.

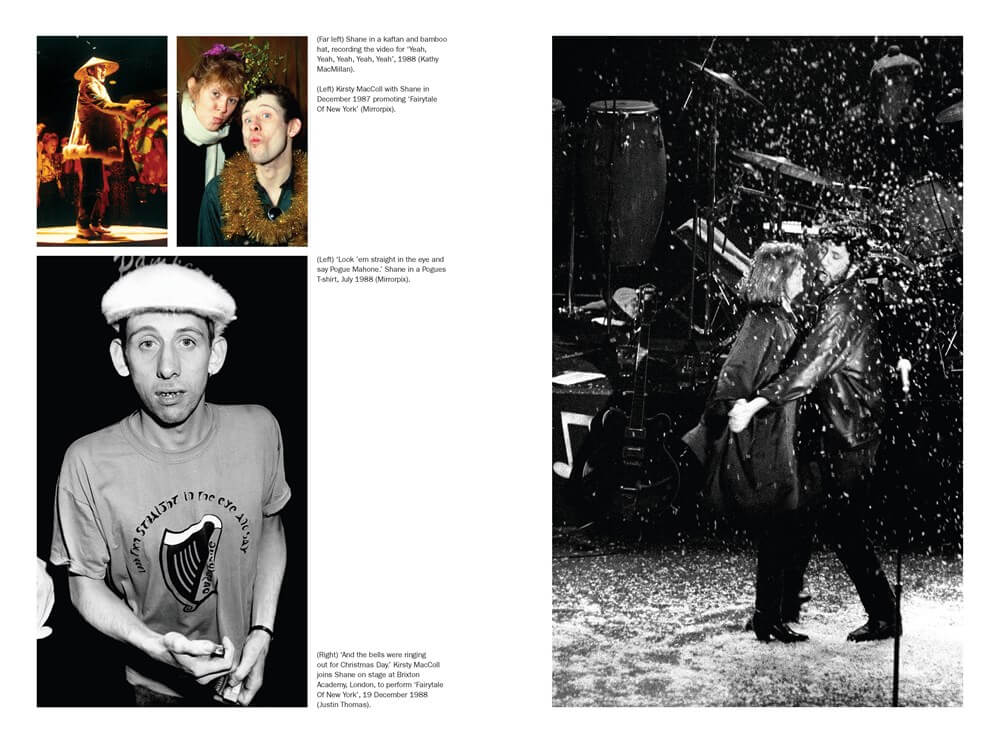

Then, of course, there’s ‘Fairytale of New York’:

Shane has said that, when Elvis Costello was producing their second album, he bet them they couldn’t write a festive track without it being ‘jingly-jangly, “Happy Christmas”’. However, Jem’s recollection is that the idea originally came from Frank Murray. ‘There was a suggestion made to me by Frank Murray that it might be a good idea to do a Christmas song and he suggested a song by The Band [“Christmas Must Be Tonight”],’ says Jem. ‘I can remember saying it would be better if we wrote our own one.’

Shane and Spider’s long-running obsession with Once Upon a Time in America also played a part in the song’s development. The first notes of ‘Deborah’s Theme’ from Ennio Morricone’s stirring soundtrack were borrowed for the opening music of the first verse (‘It was Christmas Eve, babe’).

On the other hand, the author does the song a service by introducing truth to what could otherwise just have been fable:

Another of the first people outside the band who got to hear the iconic record as the finishing touches were being added was veteran publisher and impresario Liam Teeling. He got a phone call one night and was told to get himself down to RAK Studios as soon as he could. What he saw and heard when he arrived has stayed with him: ‘I arrived there and went in and Shane was lying in a pool of vomit on the floor. Terry Woods and Steve were standing at the desk and Steve moved this big chair away and sat me down. He pressed the button and I heard, “It was Christmas Eve, babe, in the drunk tank.”

Even though much of McGowan’s life thereafter was one big slur of drugs and alcohol, the book holds up as a story of how other people cared for McGowan, not at least Victoria, his wife. These stories are far more interesting than those of big-name ones, especially the vapid words on Johnny Depp, which are of no consequence.

Sinéad O’Connor had been disgusted by Shane’s no-show at Robbie’s inquest and was distraught that another young man had overdosed at his home. So, in November 1999, when she called to see him and found him taking heroin, she took drastic action. She reported him to Kentish Town police station and had Shane arrested.

What she did for McGowan, was wondrous.

Shane would later concede that Sinéad’s unwanted intervention did have the desired effect. Asked if the episode had ended his relationship with Sinéad, he replied: ‘No, but it ended my relationship with heroin’.

All in all, what lives beyond McGowan’s deeds are his words. His songs outlived his behaviour, at least for most people. I can’t help but think he wasted much time on drugs and alcohol, not to mention how his choices affected others, and I also think all of this could have been told in a more interesting way. The author is OK, but I think what McGowan said, even at his worst, affected the outcomes in this book to a level where McGowan at his worst were more interesting than parts of the author’s best writing.

On the other hand, that’s the danger of writing about someone whose writing is far superior to one’s own. At times. When not obliterated by drugs and alcohol.