Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

In the unglorious school days of my 1980s, when I was eleven years old, our headmaster forced my class to read Go Ask Alice, a diary written by a real drug addict. The bleak story painted a very stark picture of a young girl who in her own words wrote a story where she was an everyday kid, then started dabbling with weed, ran away from home, and did far more and various drugs. Spoiler: the book ends with a note saying the fifteen-year-old died from a drug overdose.

About fifteen years after I read it for the first time, I happened to find it in a salvation army-type bin. I bought and re-read it. The first time I read it, I thought it was intense and very scary. I remember that the book felt a bit off, just like the times my class watched government-sanctioned films about the horrors using spraypaint on walls or doing anabolic steroids. It all felt dressed-up by grown-ups who weren’t connected with my generation. It felt false.

After reading the book as a grown-up, I looked into the details. Turns out, it was a sham. The book is most probably written by Beatrice Sparks, a person who very much was distraught by the fact that her publisher decided to erase her name from its cover and instead say ‘By Anonymous’.

Rick Emerson has interviewed and analysed his way through Sparks’s life, through her twists and turmoils while she tried to become famous and remain in the limelight, unconcerned of the effects her words had on millions of readers. Sparks used shock and lies as her main tactics.

Even before its whiplash ending, Alice was brutal, shoving your face in shit. If you made it past the drugs and teenage hookers (and neglected toddlers and gang rapes), Alice’s final meltdown was a long, shrieking nightmare:

Gramps . . . tried to pick me up, but only the skeleton remained of his hands and arms. The rest had been picked clean by wriggling, writhing, slithering, busily eating worms which seethed on his every part. They were eating and they wouldn’t stop. His two eye sockets were teeming with white soft-bodied, creeping animals which were burrowing in and out of his flesh and which were phosphorescent and swirled into one another. The worms and parasites started creeping and crawling and running toward the baby’s room and I tried to stomp on them and beat them to death with my hands but they multiplied faster than I could kill them. And they began crawling on my own hands and arms and face and body. They were in my nose and my mouth and my throat, choking me, strangling me. When a fly buzzes through her hospital room days later, Alice starts screaming, terrified that the creature will lay its eggs on her body. Stumbling to a mirror, Alice sees a bruised, scratched face and patchy hair. Maybe, she thinks, it isn’t really me. This wasn’t a Nancy Drew mystery or some haunted English castle. This was up close and intimate, a fear that burrowed inside you.

There was also pure nonsense. Go Ask Alice put every drug—LSD, marijuana, heroin, speed—into one lethal basket, with no attempt at nuance.

Brightly, Emerson links the tale of Art Linkletter and his daughter, Diane, into this book. Emerson was a big celebrity. When his daughter died at a young age, from throwing herself off a building, LSD was erroneously blamed; she had no drugs in her body at the time. This didn’t stop Linkletter from cavorting with Nixon. From Nixon’s secret White House recordings:

Nixon: Asia, the Middle East, portions of Latin America . . . I’ve seen what drugs have done to those countries. Everybody knows what it’s done to the Chinese. The Indians are hopeless anyway. The Burmese— Linkletter: That’s right. Nixon: Why are the Communists so hard on drugs? It’s because they love to booze. I mean, the Russians, they drink pretty good. Linkletter: That’s right. Nixon: The Swedes drink too much, the Finns drink too, the British have always been heavy boozers, and the Irish, of course, the most, but on the other hand, they survive as strong races. Linkletter: That’s right. Nixon: At least with liquor, I don’t lose motivation.

Drugs were, by and large, blamed for the moral decline of American youth and used as an excuse to get rid of ‘unwanted elements’. There were more near-incredible events:

In 1953, the CIA launched MK-ULTRA, a cluster of brainwashing experiments modeled on Nazi research. For more than a decade, government agents dosed thousands of unsuspecting Americans—including prisoners, students, and children—with LSD, often in massive amounts. In New York, the CIA went the extra mile, launching its own brothel, complete with heroin-addicted prostitutes. In exchange for dosing johns with LSD (usually via tainted booze), the women got their daily fix, immunity from arrest, and a hundred bucks a night. The agents, in turn, got to watch through one-way mirrors as the hapless men went bonkers. They called it “Operation: Midnight Climax.”

As Nixon targeted drugs as the destroyer of Youth, and with Linklater’s daughter’s death (not related to LSD, but yet blamed on the drug), Sparks saw her moment.

Sparks had it all planned out. She would cut the diary down to book size, change a few names, and presto—one cautionary tale, ready to sell. She even had a title. Buried Alive: The Diary of an Anonymous Teenager, edited by Beatrice Sparks. There were a million loose ends. Who was this girl? Where were her parents? Was this even legal? But Linkletter’s reaction was all that mattered, and he was on board.

Go Ask Alice plays out drugs like Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ plays out the Jew: they’re the root cause, and to show why, we need to show all the guts and gore. Ironically, people who flailed against the book’s descriptions of blowjobs, shit, maggots, and rape, were told to chill out: this was, after all, a real diary.

It wasn’t, but that, to Sparks and her publishers, was second to greed and vanity.

Not unpredictably, her second book was also a fake journal and about a new horror that destroyed children: role-playing.

Jay’s Journal: The Haunting Diary of a 16-Year-Old in the World of Witchcraft was published with ‘Edited by Beatrice Sparks, who brought you Go Ask Alice’ on its cover.

The truly shocking aspect of this book is, to me, how Emerson successfully shows that Sparks didn’t only model Jay’s Journal on actual persons, but thinly ‘anonymised’ the book so badly that people could easily see who’s said and done what. Who cares about the truth?

Emerson points out that to know whether Go Ask Alice was fiction or non-fiction, one had to visit the American government’s Library of Congress. Or, wait:

So there you are, standing in the bookstore, looking at the new releases. Fiction, nonfiction, memoir, anthology—how can you tell them apart? At first, it seems easy. Check the back cover, or maybe the spine, or that inside page with all the tiny print. But what if the book is unlabeled, like the Prentice-Hall hardcover of Go Ask Alice? What if there’s no “fiction” or “nonfiction” label, but the cover says “a real diary,” like the Alice paperbacks? Here’s a good one: What if the front cover says “a real diary,” the spine says “autobiography,” and the inside page says “fiction”? Avon’s 1982 edition of Alice is printed exactly that way, with zero explanation. What if the labels disappear again (as they did a decade later), leaving just “a real diary” and “Anonymous,” with no other info? Ah—but maybe you live in the internet era, and information is yours for the asking. Seek, and ye shall find. You go online, search the Library of Congress database, and find the entry for Go Ask Alice. “Fiction.” Bam! Case closed. Except, wait, because here’s a second Library of Congress entry for Go Ask Alice, and this one says “not fiction.” That’s the actual designation: “not fiction.” You look again. Is it a different book with the same title? No, it’s the very same Go Ask Alice. So now, for this one book, there are two conflicting Library of Congress entries, a hardcover with no information, millions of paperbacks saying “a real diary,” and at least one edition that doesn’t even agree with itself. What the hell is going on here?

The real people that Sparks used to write Jay’s Journal weren’t just subject to their local communities. People travelled to one person’s grave to perform rites, no doubt something that would never have happened if Sparks hadn’t concocted the book.

The book must have done its part to trigger satanic panic in the USA.

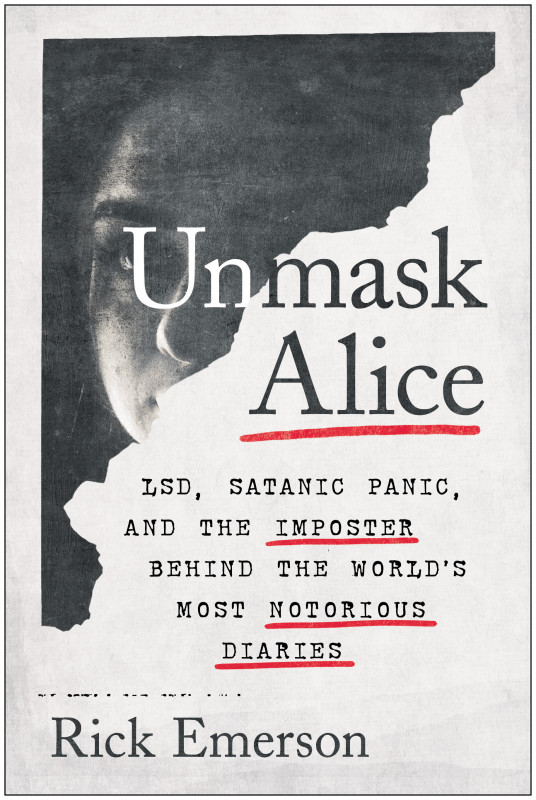

By writing Unmask Alice, Emerson has shown Beatrice Sparks for what she really was: a fame-hungry liar who didn’t care about the lives she plundered. Naturally, people like Richard Nixon and those working at Prentice Hall/Simon & Schuster, who published some of her books, deserve shame for being as bad as she was. Even though this book is slightly uneven in rhythm, Emerson’s detective work brings life into the book, life that sustains it throughout. This is an easy read that should make readers angry for life, against slander, and question clarion calls for ‘justice’.