Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

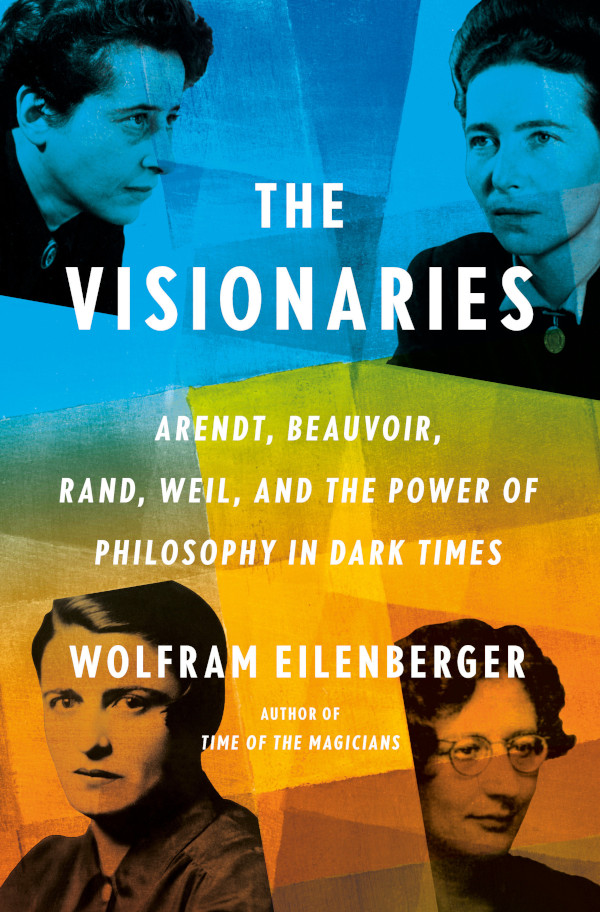

Wolfram Eilenberger’s previous book, Time of the Magicians, was about four German philosophers: Heidegger, Benjamin, Cassirer, and Wittgenstein. This new book, The Visionaries: Arendt, Beauvoir, Rand, Weil, and the Power of Philosophy in Dark Times, is even more interesting. The book covers ten years—1933–1943—in the lives of four individuals who ultimately made and created ways through which we can see ourselves and our times.

Simone de Beauvoir, already in a deep emotional and intellectual partnership with Jean-Paul Sartre, was laying the foundations for nothing less than the future of feminism. Born Alisa Rosenbaum in Saint Petersburg, Ayn Rand immigrated to the United States in 1926 and was honing one of the most politically influential voices of the twentieth century. Her novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged would reach the hearts and minds of millions of Americans in the decades to come, becoming canonical libertarian texts that continue to echo today among Silicon Valley’s tech elite. Hannah Arendt was developing some of today’s most important liberal ideas, culminating with the publication of The Origins of Totalitarianism and her arrival as a peerless intellectual celebrity. Perhaps the greatest thinker of all was a classmate of Beauvoir’s: Simone Weil, who turned away from fame to devote herself entirely to refugee aid and the resistance movement during the war. Ultimately, in 1943, she would starve to death in England, a martyr and true saint in the eyes of many.

This book is chronologically told and deftly jumps between tales of the main players. Eilenberger nicely keeps up rhythm and tension, the later often because of major events taking place during World War Two.

The main players are all on display just as they’re at the cusp of forming their work in the coming decade. I adore two of them (Weil and Beauvoir), I greatly respect another (Arendt), and I have little care for Rand’s work; I strongly dislike many of her egoistic ideals, most of which are connected to Nietzsche. On the other hand, I deeply like how Eilenberger has contrasted Rand with the other main persons in the book. It’s well done, and Rand isn’t displayed as a two-dimensional character. Her family escaped from Lenin’s Russia during the October Revolution in 1918. It’s not surprising that she’d want to rebel against what Eilenberger calls ‘a society of state-produced slaves’. That’s what she did by furiously and tirelessly writing for the power of the individual against the opium-feel of the collective. To me, Eilenberger’s greatest strength in displaying Rand is via one of her creations: Howard Roark, the male protagonist in The Fountainhead, one of her massively successful novels.

All of the main players in Eilenberger’s book had their bouts with self-doubt, all of them failed at times, all of them succeeded. We get to follow them through all of it, for a decade.

In the 1920s, Arendt studied with Martin Heidegger, one of the leading philosophers of the time. She studied metaphysics from a pragmatic perspective, preferring concrete case studies to theories that seemingly led nowhere. She also studied with Karl Jaspers, another major philosopher. She carried enough integrity and heft to withstand his nationalistic writing at the time in this letter in response to a study by Jaspers’s: Max Weber: German Essence in Political Thought, Research, and Philosophy

Berlin, 1 January 1933

Dear Professor

My deepest thanks for the Max Weber, with which you have given me a great deal of pleasure. There is, however, a particular reason why I am only thanking you for the text today: both title and introduction have made it difficult for me to comment on the book. It does not bother me that you portray Max Weber as the great German but, rather, that you find the “German essence” in him and identify that essence with “rationality and humanity originating in passion.” I have the same difficulty with that as I do with Max Weber’s imposing patriotism itself. You will understand that I as a Jew can say neither yes nor no and that my agreement on this would be as inappropriate as an argument against it… For me, Germany means my mother tongue, philosophy and literature. I can and must stand by all that. But I am obliged to keep my distance. I can neither be for nor against when I read Max Weber’s wonderful sentence where he says that to put Germany back on her feet he would form an alliance with the devil himself. And it is this sentence which seems to me to reveal the critical point here…

At the same point in time, twenty-four-year-old grammar-school teacher and trade-union activist Simone Weil fled Germany. A year earlier, she had predicted Hitler’s rise to power yet still saw good in the communist party; her views on collectivism via Marx changed during that same year, where she published an article:

Weil’s article, published in La révolution prolétarienne on August 25, 1933, under the title “Prospects—Are We Headed for the Proletarian Revolution?,” could hardly have caused greater offense. In it she establishes the structural similarity between newly fascist Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union.

In only a few months Hitler had: Installed… a political régime more or less the same in structure as that of the Russian régime as defined by Tomsky: “One party in power and all the rest in prison.” We may add that the mechanical subjection of the party to the leader is the same in each case, and guaranteed in each case by the police. But political sovereignty is nothing without economic sovereignty; which is why fascism tends to approach the Russian régime on the economic plane also, by concentrating all power, economic as well as political, in the hands of the head of state.

At the same time, Simone de Beauvoir was teaching 15–18-year-olds while building her philosophical world, both beside and together with Jean-Paul Sartre, another French philosophical giant-to-be. Both of them were apolitical and so tightly tied together that she had ‘the most brazen indifference to public opinion’. Eilenberger does a fine job in showing both Beauvoir’s utter devotion—and misery—in her care and love of Sartre and also in her personal growth. On Beauvoir and Sartre’s big break in relation to phenomenology and—what they themselves would partly create—existentialism:

At the beginning of 1933, the pair arranged to have a drink with a former fellow student, Raymond Aron. Aron was just back in Paris after his study year in Berlin. At their meeting in the Bec de Gaz bar on rue du Montparnasse, the returning traveler told them about an entirely new German trend in philosophy called “phenomenology.” As Beauvoir recalled: “We ordered the specialty of the house, apricot cocktails; Aron said, pointing to his glass, ‘You see, my dear fellow, if you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!’ Sartre turned pale with emotion at this. Here was just the thing he had been longing to achieve for years—to describe objects just as he saw and touched them, and extract philosophy from the process. Aron convinced him that phenomenology exactly fitted in with his special preoccupations: by-passing the antithesis of idealism and realism, affirming simultaneously both the supremacy of conscience [consciousness] and the reality of the visible world as it appears to our senses.”

Sartre and Beauvoir soon discovered, via their own original readings, the works—as intense as they were linguistically demanding—of the mathematician and philosopher Edmund Husserl. In Göttingen and Freiburg before World War I, he really had established a new form of philosophical inquiry. Under the slogan “Back to things themselves,” Husserl required that his students provide as precise, undistorted, and, most important, unprejudiced description of what appeared to consciousness as given. How do things really show themselves to consciousness?

Husserl called this almost meditative attitude of concentration on the purely given, avoiding any addition or deviation, “reduction.” And one of his first central insights from this consisted in the following: Consciousness, however it is concretely shaped or whatever it may be concerned with, is always consciousness of or about something! We taste the sweetness of liqueur, we are disturbed by the noise of a car that rattles by, we have memories of our vacation in Spain, we hope for good weather. To the extent that consciousness can be grasped at all, it must be grasped as consciousness of something. To this essential directedness toward or action of consciousness Husserl gives the name “intentionality.” In fact, an apricot cocktail in the middle of Paris was enough to explain this reality.

Closely related to this, Husserl identified a second characteristic quality of consciousness: By virtue of being directed (intentional), consciousness is always also about things that are essentially external to and different from itself (liqueur, a car, the landscape, the weather). To be itself, consciousness therefore always forces its way out of itself into the open and into other people. In other words, it has an essential urge to go beyond itself—or, to quote Husserl, to “transcend” itself.

Aron had correctly explained it to Sartre and Beauvoir, he had fully grasped the philosophical explosiveness of this approach: Phenomenology opened up a radically new way of understanding one’s own existence. In Husserl’s world, consciousness did not take its bearings passively from things (realism), nor was consciousness a compass toward which things were directed (idealism). It was rather that realism and idealism were unshakeably related to each other without ever really becoming one. The world does not entirely disappear into consciousness, but neither does consciousness dissolve entirely in the world. As in a perfect dance, they are both entirely themselves, and yet one is nothing without the other.

This philosophical change is not short of life-altering for Beauvoir and Sartre.

Meanwhile, Simone Weil decided to avoid the trap of theoretics that’s often a major problem for thinkers; she risked a reality check ‘and in her factory diary she even speaks of her desire finally to make “direct contact with life.”’ Even though Weil set a time limit for her project, she carried a feeling of slavery and wore down over a short period of time. This leads to a paragraph that clearly shows part of both Weil and Eilenberger’s brilliance:

It should have come as no surprise or special insight that Weil was not made for this kind of life. But what human being was, or would be? Were there sentient beings who could maintain their self-respect and dignity under such conditions? These were the questions addressed by her now complete philosophical “testament.” They had been among the leading questions in the analyses of Karl Marx. Except that he, as Weil says in her Reflections, provided essentially mythical answers, with fatal consequences for the proletarians of all countries, who were to be liberated in the course of a revolution. For all its clear-sightedness and aspiration to scientific status, Marxist analysis was burdened with a pseudo-religious philosophy of history. The central mistake lay in Marx’s own assumption, neither explained nor examined, that all progress in humanity’s productive forces allowed people to advance along the path to liberation. Accordingly, the process toward a communist society of true individual freedom is reconstructed by Marx as the history of the technologically and mechanically achieved increase in productive forces. If the arc of suffering of the proletariat was long and harsh, it bent in the end inexorably toward their liberation. Thanks to the “increase of productive forces” the history of humanity was fired by an intrinsic goal that could not be missed. It’s worth quoting Simone Weil’s critique of this dogma at length. Not least since this passage on the Marxist fetish for the growth in productive forces reveals the common but hidden roots of both a capitalist and a communist conception of history. Both ideologies, in Weil’s view, under the auspices of the myth of infinite growth, dreamed up the end of the history. Both dreamed of a global systematic victory on an ultimately economic basis. Of a liberation of humanity not only from the yoke of work but also from the yoke of a reality that contradicted our desires. In other words, under the cloak of science both finally revealed themselves as caught up in glaringly unscientific, plainly nonsensical fundamental assumptions. Marxists . . . believe that all progress in productive forces causes humanity to advance along the road leading to emancipation, even if it is at the cost of a temporary oppression. It is not surprising that, backed up by such moral certainty as this, they have astonished the world by their strength. It is seldom, however, that comforting beliefs are at the same time rational. Before even examining the Marxist conception of productive forces, one is struck by the mythological character it presents in all socialist literature. . . . Marx never explains why productive forces should tend to increase. . . . The rise of big industry made of productive forces the divinity of a kind of religion. . . . This religion of productive forces, in whose name generations of industrial employers have ground down the labouring masses without the slightest qualm, also constitutes a factor making for oppression within the socialist movement. All religions make man into a mere instrument of Providence, and socialism, too, puts men at the service of historical progress, that is to say of productive progress. That is why, whatever may be the insult inflicted on Marx’s memory by the cult which the Russian oppressors of our time entertain for him, it is not altogether undeserved.

World War Two caused a massive flux of refugees throughout Europe and the rest of the World, which, in turn, forced people to think about identity. What George Orwell described as doublethink—a process of indoctrination in which subjects are expected to simultaneously accept two conflicting beliefs as truth—is what Arendt came across in many ways. Jews have since long been blamed for anything under the sun; some countries that officially opposed Hitler were also vehemently discriminatory against jews. In turn, the Biltmore conference was a turning point for Arendt. The conference marked the point in time when ‘Palestine be established as a Jewish Commonwealth’, in other words:

The actual Arab majority population that also lived there was to be given only minority rights (not including the right to vote). Arendt was filled with fury and, even more than that, with despair. She saw the Biltmore resolutions in the name of Zionism as a version of the ideal behind the solution to the “Jewish question,” which she was convinced had led to political anti-Semitism and also to a “Jewish question” in the modern sense of the term: a fixed idea of a nation-state ideally forming a completely binding unity of people, territory, and state—in which the Jews as a people must inevitably be seen as a deeply disturbing Other.

For Arendt, the Biltmore resolutions were a profound error, in fact a betrayal of the originally emancipating goals of the Zionist movement. In terms of realpolitik, she also considered them both nonsensical and, in the medium term, self-destructive. In her many raging articles over the following weeks and months she described as absurd the idea that a majority (Arabs) within a democratic Jewish Commonwealth should be granted only minority rights. Equally illusory was the idea of a supposedly sovereign nation-state that had to remain permanently dependent on another protective state for its existence and its ability to flourish. This fate, in terms of the map, seemed inevitable for a purely Jewish Palestine: Nationalism is bad enough when it trusts in nothing but the rude force of the nation. A nationalism that necessarily and admittedly depends upon the force of a foreign nation is certainly worse. . . . Even a Jewish minority in Palestine—nay even a transfer of all Palestine’s Arabs, which is openly demanded by the revisionists—would not substantially change a situation in which Jews must either ask protection from an outside power against their neighbors or come to a working agreement with their neighbors.

Arendt went against popular opinion, as with all main players in this book.

In the history of humanity, there can have been few individuals more productive than was the philosophical resistance fighter Simone Weil during only four months in that London winter of 1943: she wrote treatises on constitutional and revolutionary theory, on a political new order for Europe, an investigation into the epistemological roots of Marxism, of the function of political parties in a democracy. She translated parts of the Upanishads from Sanskrit into French, and wrote essays on the religious history of Greece and India, and on the theory of the sacraments and the sacredness of the individual in Christianity and, under the title The Need for Roots, a 300-page redesign of the cultural existence of humanity in the modern age.

Weil died for her ideals and because of tuberculosis. Eilenberger beautifully describes the last part of her life, painting a loving picture of her thoughts and philosophy on the road. She renounced food and embraced God, a way of mysticism, salvation, and selfless perception. I feel the book nails her thoughts with more precision than those of Beauvoir and Arendt. At first, I felt that Rand was given more time than she was due, but on second thought, her ideals and ideas are given sufficient space to describe her hatred against collectivism and from where she came; this is also, I believe, a fine display of how Rand locked herself in her own mind and never truly escaped authoritarianism.

I remember Alan Greenspan, who said ‘worker insecurity’ is good:

After her return to New York in 1951, Rand attracted a circle of loyal disciples. One of them was Alan Greenspan, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve from 1987 until 2006, appointed by President Ronald Reagan. Greenspan had earlier been appointed chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Gerald Ford, and Rand was present at Greenspan’s swearing-in.

All in all, this book is an interesting and fragmentary look into a decade of the lives of four very important individuals who all were marked by a quickly changing point in time for humanity. The book is fragmented in a good way; these persons not only were marked by time, but marked our time by being themselves, moving with integrity and determination. I really like this book. In case you’re interested in Beauvoir, I also recommend Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails, Kate Kirkpatrick’s Becoming Beauvoir, and Deirdre Bair’s Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography.

The Visionaries is published by Penguin Press on 2023-08-08.