Colin Barrett - 'Wild Houses'

A short-story radiant's first novel. It's worth reading and stands out.

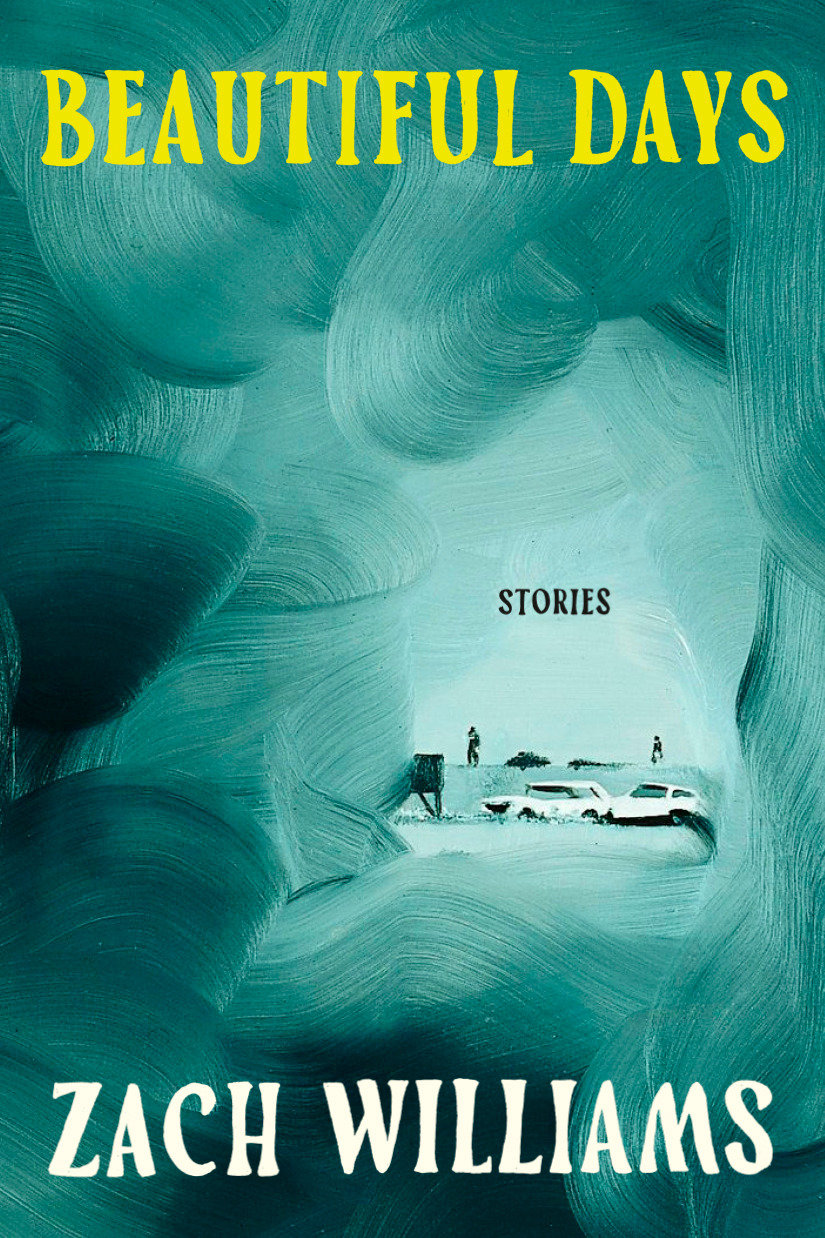

When I first read ‘Trial Run’, Zach Williams’s modern political rollercoaster of a short story, we meet persons polarised:

I dropped my bag, put my coat on the chair, sat and swiveled so neither Manny nor Shel was in my line of sight, and took out my laptop, running my fingers along the deformed place where the battery had swollen. A note from Lisa, our manager, still sat near the top of my inbox—“Stay warm, see you back at the office on Thursday.” But just above it was the one Manny had mentioned, from TruthFlex00-09@gmail.com: Lisa Horowitz is a CULTURAL MARXIST—¡WHITE GENOCIDE!

If that had been all there was to Williams’s prose, I’d have left it on the floor; what kickstarts Williams into being is his style:

Nora—Bea’s mother, my wife—had been dead a little more than one year. She had died suddenly and by chance, in what I suppose you’d call an accident, just walking to the train from work. The shock of dislocation that I experienced after it happened had been nearly physical, like passing into a new and different city—the streets roiling and unsteady, the buildings overhead a dark mess of stalagmites. Eventually the sensation receded, though I couldn’t forget it, and it kept coming back, each time a little stronger. I had to learn to blink it away. For months that’s what I did, but it came to feel hopeless. The sensation seemed to want to increase toward some extremity, a point of complete saturation. What I grew to suspect was that, sooner or later, I’d have to let it.

Now that’s effective text, simple and American, in a sense Stephen King-ish, peppered with commas. When at its best, Williams’s prose is taut and yet relaxed, striking a strange rhythm between what’s expected (American life) and what is coloured in a way that drew me in, that called me to read more.

Where William S. Burroughs described both the everyday existence of people in spite of extreme circumstances both internal and external, Williams dives only into what happens inside of ourselves, by using the external as a ruse. The mundane feeling that his prose first evoked in me was lost after a while, a hypnotic effect that reeled my senses into thinking there was first not much behind simple arrangements of the externals.

What happened to those years, between your birth and Maureen’s death? Sixteen of the fucking things. The art gallery folded. I found bookkeeping work with a small theater company and spent weekends getting high with my city friends. I said no more kids; Maureen knocked out a wall and redid the kitchen. My hair came in gray, I worried about my erections, the United States defaulted on its debt. But still I read hopefully about late bloomers. Did you know that Philip Glass drove a cab into his forties? When you were thirteen, I converted the attic to my studio and took up painting again. As I worked, I tried to be loose in my body, rolling my shoulders, waving the energy up my spine, like before. Around that time, I had a dream. It’s just past sunset and I’m back in Columbus at the insurance firm. The room is dark, filled with the hum of ghosting computers. Down by the dumpster I see a bonfire built from big sticks, crossed at the top, shooting sparks into the air. And standing beside it is Joe Daly. Wearing a suit of black feathers. Terrified, I sink to the floor, and there I become conscious of a tug between my legs. Hooked directly into my scrotum is an old 32-pin connector cable. It’s running to one of the computer towers. Running to Ghost Image. And then you woke me up. You said you’d missed the bus.

As many debutante authors are prone to do, there is the counting of things, there is the addition of too much at times, but it does not weigh down the book as a whole; Williams is too graceful and careful a writer to do something as stupid as quickly knock out a shit book, to look down on the reader, to cash in.

This is a collection of viscerally told pieces, reminiscent of an Alex Garland film without most philosophy. I can’t say these stories are memorable, but that’s beside the point of a good short-story collection, a bit like those by Kurt Vonnegut. I eagerly await Williams’s next book.