Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

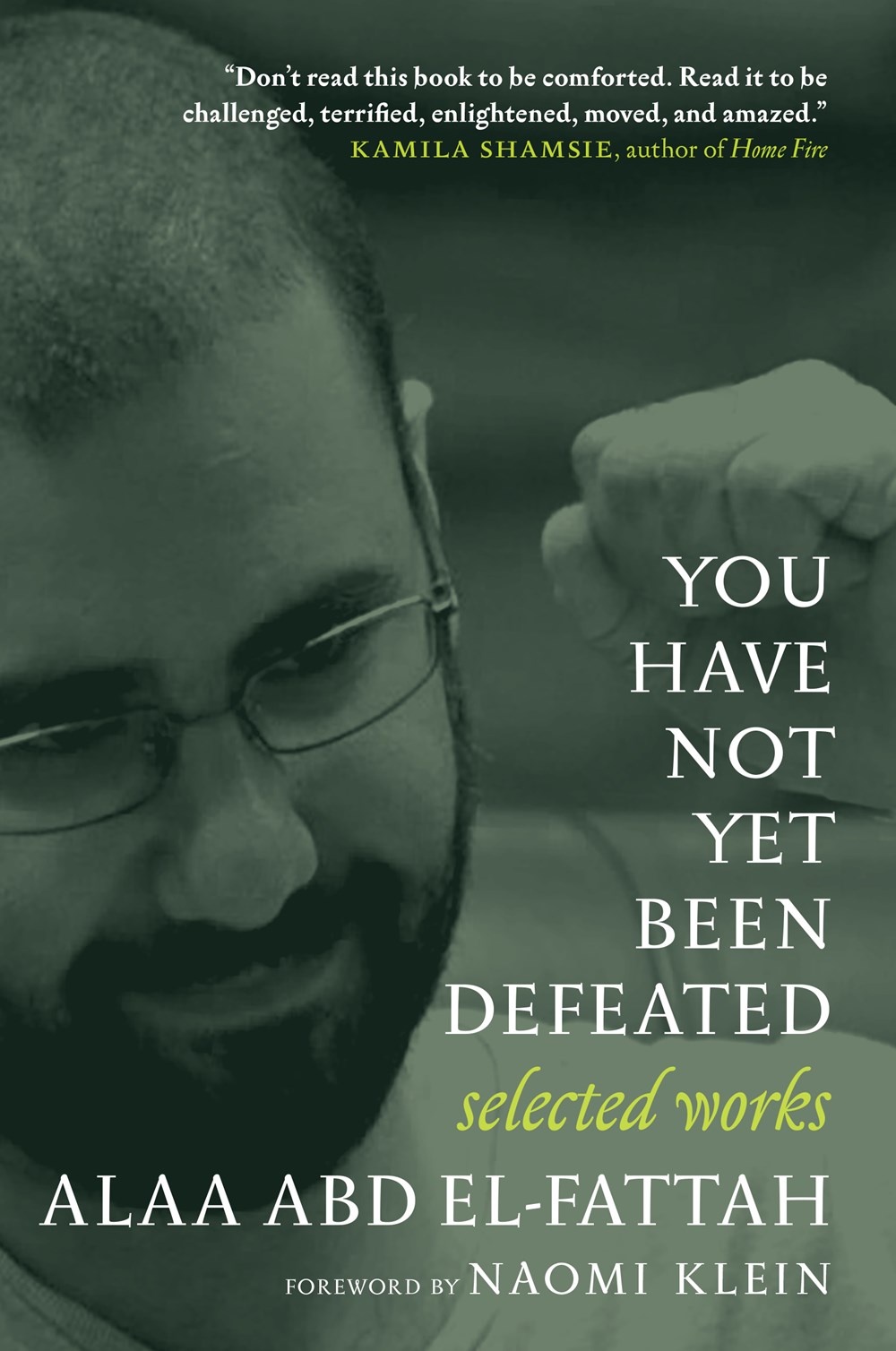

In December 2021, Alaa Abd el-Fattah was sentenced to five years in prison for ‘spreading fake news’. Now is the time to read urgent words hurled at us from a coruscating mind and decide for yourself: is writing about protests and a fascist government ‘fake news’? If you ask the current Egyptian state, everything that is against their propaganda is probably fake news. Ask me, and I think he’s in prison because he’s said too much and Egypt is an authoritarian state.

I had not read Alaa Abn el-Fattah before I picked up this collection of texts that are written before, during, and after many of his stints in prison.

My first impression was ‘here’s a hyperkinetic person whose writing pours out of him to keep up with what’s happening’. He was young, he was fire. He still is.

As I read Alaa’s words I’m struck by what Noam Chomsky often has responded when asked what to do about injustice. He’s said people who are directly affected by injustice rarely, if ever, ask the same question: they act.

Alaa acts.

5 January 2013

Are you one of the privileged few with a bank account? Well done, mate—and you get about a 9 per cent return, I guess? But do you know what the bank does with your money to get you that return? It lends it to the government at 16 per cent. That’s pretty much their main activity, or do you believe all that talk about investments? So if the bank is making 16 per cent on your money, and only giving you 9 per cent, where does the rest go? Into the pockets of the managers and senior staff at the bank. Or are you going to believe it’s all administrative expenses? OK, then how does the state pay that difference? From your money, mate. From your taxes, from austerity policies and slashing services and cutting subsidies to the majority—who are not well-off, and do not have bank accounts—or did you think this was all from Suez Canal revenue? OK so if the country is on the verge of bankruptcy and crisis like they’re saying, then what will happen? Most likely the pound will drop, so the value of your money in the bank will drop, and prices will go up for both you and those who are not well-off and have no money in the bank. And if we really do get to the point of bankruptcy the bank could close down and all your money would be lost, but that’s unlikely.

He writes about being (illegally) arrested, of how prisons never change ideas, on technology.

Certainly the prospect of the sharing economy giving rise to a world war is unlikely, but that’s not to say that it doesn’t involve any violence or repression, because this idea of a clear separation from the material world is a myth. Uber could never have flourished were smartphones not already widely available. Smartphones are produced in large numbers at relatively low cost, with a substantial profit margin for Apple and the like. The model relies on enormous Chinese factories where workers suffer appalling working conditions: sometimes labourers are detained at their workstations in what basically amounts to forced labour. Apple has faced repeated scandals over working conditions, most notably the high suicide rate among workers. Those factories also rely on rare minerals, which are extracted in primitive mines in Africa where child labour is rife, health and environmental conditions are dire, and profits fuel vicious conflicts between militias and armed gangs.

Alaa enthralls the reader. He digs into hard ground, sifts through what’s found, uses humour and easily understood language to eloquently visualise the results and the future of life under dictatorship. He mainly writes about politics, humanitarian issues, and people, but his focus and radiance is on and in Egypt; his voice resounds clearly and points to the fact that Egypt is, just like himself, in jail, and not run by people who are elected by the Egyptian people.