Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

“I’m really in the way as a person,” Thompson said in 1978. “The myth has taken over.”

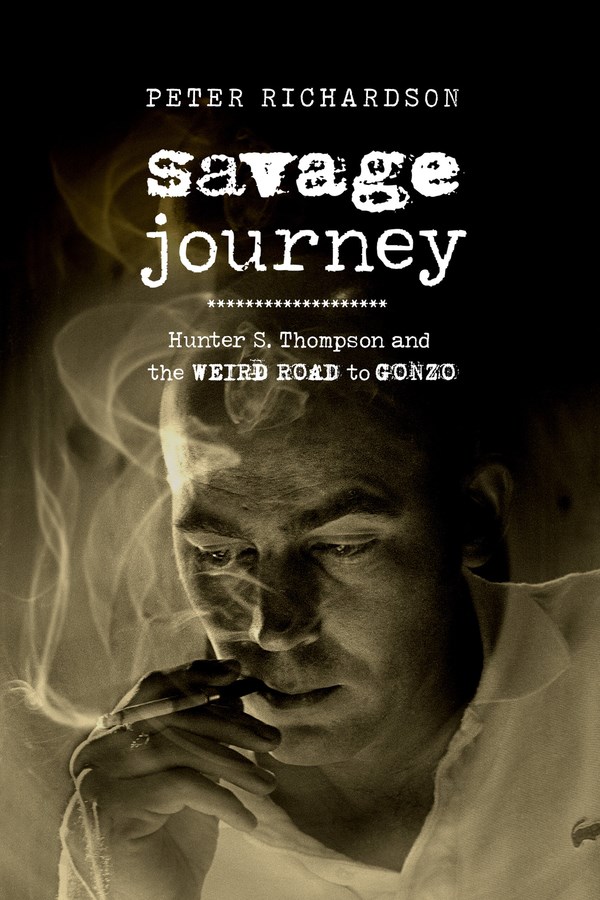

This is the second book on Hunter S. Thompson that I’ve recently read; the first one is David S. Wills - ‘High White Notes - The Rise and Fall of Gonzo Journalism’, which focuses on how Thompson invented gonzo, his style of writing. This book is far more biographical and has pros and cons when compared with Wills’s book.

Richardson has done a fine job in going through Thompson’s sea of writing, easily sifting through the good and bad. The good lies mainly in how Richardson sees Thompson from a helicopter picture. The bad is that Richardson gets too deeply into subjects that he’s written about previously, mainly Ramparts magazine and Carey McWilliams, perhaps mainly known for having edited the magazine The Nation.

Still, there are many nuggets found here. Richardson does not shy away from criticising Thompson on a variety of subjects, for example, racism, bad writing, and abuse (of both women and substances).

It’s lovely to read on how Richardson weaves a tale of why Thompson started writing, although Wills goes deeper into Thompson’s genesis.

McKeen also observed that Prince Jellyfish bore the influence of J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, which its author described as “celebratory, boisterous, and resolutely careless mayhem.” Set in postwar Dublin, the comic novel depicts the daily rounds of Sebastian Dangerfield, another selfish and arrogant charmer who beats his wife and drinks away the family’s limited funds. Critics described Dangerfield variously as “impulsive, destructive, wayward, cruel, a monster, a clown, and a psychopath.” The Ginger Man was first published in 1955 by the Olympia Press, whose catalog included works by Henry Miller, Vladimir Nabokov, Samuel Beckett, and William Burroughs. Donleavy’s novel appeared in the Traveller’s Companion series, which was known primarily for its erotica and banned in Ireland and the United States. (Grove Press reissued the novel, which eventually sold more than 45 million copies worldwide.) Donleavy was furious that the novel was mistaken for smut, but its transgressive status probably heightened the appeal for Thompson. Reading The Ginger Man, Thompson said later, “made up my mind that I had to be a writer.”

There are some interesting comparisons made between Jack London and Thompson.

Like Thompson, London believed that fiction was more truthful than mere fact. “I have been forced to conclude that Fact, to be true, must imitate Fiction,” London wrote. “The creative imagination is more veracious than the voice of life.”

I like Richardson’s writing style: at times, stringent, other times, relaxed:

Hunter was absolutely obsessed with the Senate hearings and Robert Kennedy. It was the only damn thing he would write about in that period. He was fascinated with all that shit. He really liked the job Bobby Kennedy was doing, and he stopped writing about sports altogether.

All in all, this is a pleasant read about a groundbreaking, unpleasant, mercurial, and weird person whose best qualities left a magnificent dent in not only American writing but everywhere. Thompson appears to have been like a caged lion: magnificent to look at from afar but lethal up-close.