Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

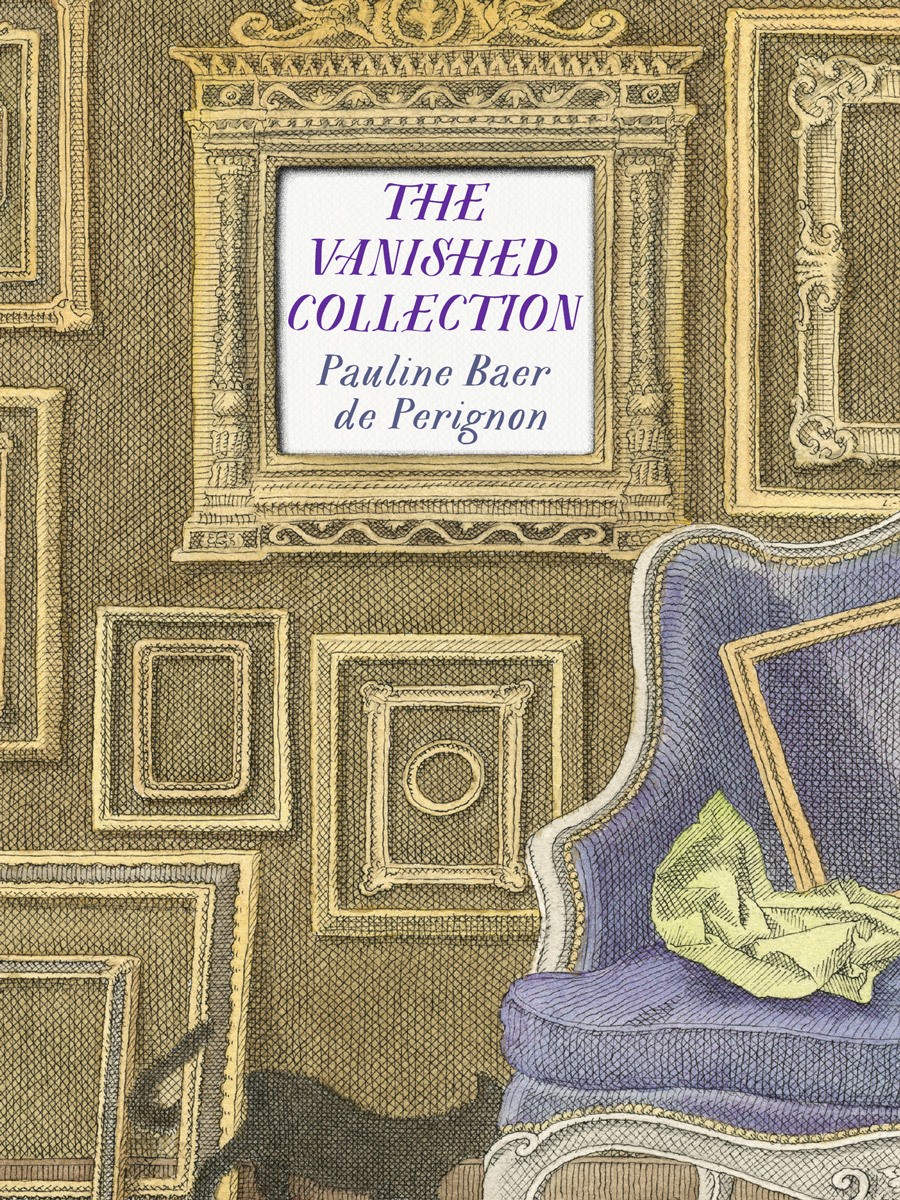

This book is a hunt for a better future. It is a righteous hunt, where things that have been stolen from your family should be returned. You know the feeling when your family’s been done wrong and you want to correct things: this book is that feeling, plus a lot of Agatha Christie thrown in.

Baer, the author, learns that artworks owned by her great-grandfather were stolen by the nazis during World War II. She starts digging, finding out truths while turning over rock after rock.

Baer’s spirit and relentlessness provided this book with sprite, much needed to turn this into the detective story that it actually is; it could easily have been a throw into the doldrums, a navel-gazing type of story, but it is not.

Basically, Andrew had found a list of paintings that our family had declared stolen during the Second World War—the same paintings that Jules Strauss was supposed to have sold at auction in 1932. Andrew now suspected that the paintings had not in fact been sold. “What are the paintings on Andrew’s list?” Henri wanted to know. “Degas, Renoir, Monet . . . I’m not sure. Andrew does. Selling Impressionist and modern paintings is the family business. I’m sure he knows what he’s talking about.”

This book reminds me of Menachem Kaiser’s Plunder, a deeply moving tale of a man’s search to reclaim what the nazis stole from his family.

I won’t spoil things, but I will say this: it’s remarkable to see Baer uncover proof of how nazis set up fake auctions to hide how they stole possessions, and even more remarkable to follow Baer in discovering how far super-wealthy museums and current ‘owners’ of artwork will go to keep their stolen goods.

Even before the invasion of France, the Germans had drawn up a list of major French collections. They certainly would have known about Jules. Every Jewish collector figured on the list drawn up by the ERR, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, the special task force headed by the fanatical Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, who was tried at Nuremberg after the war and executed for war crimes. Beginning in July 1940, Rosenberg was responsible for the organized plunder of works of art belonging to Jewish collectors in occupied France. Around twenty-two thousand artworks were expropriated in the course of the war.

Baer went a long way in not only finding what was stolen from her family, but also in learning about art history.

As we traipse in her footsteps, we see how she unveils truth one step at a time.

So there was a dossier here for a restitution claim filed by my great-grandmother. My discovery put an end to weeks of doubt: if Marie-Louise had filed a claim, that must mean that my family had had their art expropriated.

It’s a real detective story, both adventurous and horrifying.

All in all, this book is an easy read, a kind of detective-cum-vengeance book. Of course, vengeance is especially sweet when it is deserved, especially when it is brought to greedy people.