Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

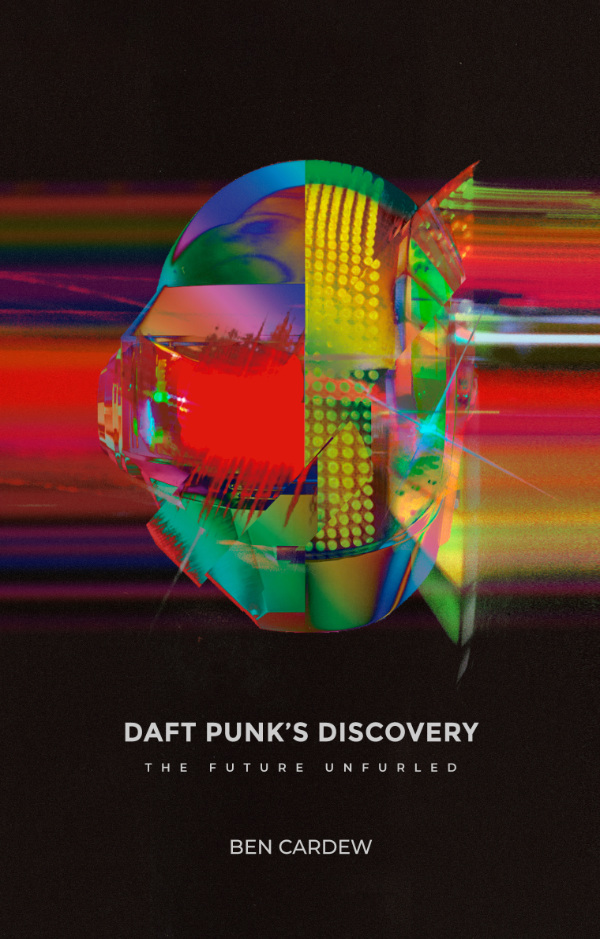

So far, no books have been written about Daft Punk with help from the band. They are elusive, seemingly acquiesce to what happens around them. Still, they’re not robots: they know what’s going on, and Ben Cardew’s book acts as testament to this.

The title is forked: it’s mainly about Daft Punk’s album ‘Discovery’ and tells a story of how two young men wanted to make music, experimented, made more music, collaborated, experimented, went retro, and hung their hats up.

Daft Punk ceased to exist a few months back, eight years after their latest album was released. The band’s end was announced with a video edit from one of their films. The end. This caused ripples for a lot of people. EDM acts have lauded Daft Punk forever, which is funny as De Homem-Christo has stated that EDM ‘is energy only. It lacks depth.’ Daft Punk have been at the very vanguard of shaping popular dance music for years, from scratchy acid trax to a video dog to a vinyl album that sounded like it was made in the 1970s.

Cardew has not had access to the members of Daft Punk while making this book. He has, in the past, briefly interviewed them for music magazines. At this point in time, it could be hard for any journalist to interview them. Perhaps they’re not interested, perhaps they’re bored with the entire industry; only they (and the people they’ve told) know.

Not that we care. Why should we? Cardew wrote his book without their blessing or help, and that can be good. Remember: Daft Punk made their music without any kind of blessing from anybody, as with most great art.

Until they eventually want to create a book about themselves, this book serves as a rememberance, a desktop analysis of things past, paired with interviews with interesting people who musically worked both with and at the same time as Daft Punk.

Bangalter is known as more of an experimenter, an early adopter who apparently owned one of the first Mac computers in France; De Homem-Christo is more restrained in his tastes. In Daft Punk Unchained, Eric Chédeville called De Homem-Christo, his partner in Le Knight Club, “more mystical”.

“He wants just one thing, not two,” he explained. “And until he finds it, everything else is shit.” “Guy-Man is really pure,” Chédeville tells me. “He is a guy who doesn’t make any concessions. In music, for example, I am a musician, I went to music school, I can play two or three riffs and think that the two or three are good. With Guy-Man, it’s not like that. With Guy-Man you can play one thousand riffs; if he doesn’t hear the good one, nothing is good.”

Darlin’ was the first band that they were in together. A band named after a Beach Boys song says more than meets the ear: they could be purists. They are most likely nerds. Nothing wrong with that. It carries attitudes and emotions, things that young bands should carry with them. They were influenced and wanted to make their own, like scores of musicians before and after their advent. Burn, burn, burn.

Cardew has dissected the genesis of Daft Punk in intriguing ways. He not only juxtaposes songs that Darlin’ released with other tracks of the time, but goes into analysis of how they curtail what should not be in Daft Punk, and how the band made it so. Here, the title of the book is no misnomer: analyses are next to interviews with musicians and collaborators that all bring depth and flavour to the book.

Bangalter told Melody Maker in 1997 that the album was made very cheaply - “No studio expenses, producers, engineers” - and that the duo had no real intention of making a full album until they realised they had assembled enough tracks.

Consider how Homework was made, compared with the ultra-slick studio mastercraft Random Access Memories, which seems to be Daft Punk’s last album.

“We asked ourselves what would be the meaning of the music we were doing,” Bangalter told MTV, “Could electronic music, outside of a club, be the soundtrack of our lives? Windowlicker was a real shock for us because it was neither a purely club track at one extreme of the electronic-music spectrum, nor just a very chilled-out downtempo relaxation track at the other end.”

Even though Daft Punk carefully constructed an images of themselves as robots, creating their music in tandem with their own story, there are a lot of examples throughout the book of the band as fans, music lovers, and careful artists.

I loved Homework, a brilliant album. I liked how it went up and down in tempo and quality. I enjoyed how unpolished it felt while it contradictory felt like a very carefully constructed album, as though it had been made using LEGO, the result a monster, something bigger than the totality of its parts.

When that album came out, it blew almost everything else out of the water. Paris is Burning became big again. And then Alive 1997 came, which made many people reconsider how they were making music and also DJing:

Ian Pooley, who supported the band on the German leg of the Daftendirekt tour, says the band played “live, live - no faking”. “In the 90s, even me when I would play live occasionally, I would throw in a DAT tape because I needed to have a break to load more samples,” he says. “The samplers back in the day couldn’t have so much memory. So actually, you would have to load in between. But I think they managed to [avoid this]. They had identical copies of the machines as well, just as a backup, just in order to get the full 90 minutes through. And also always in sync with the light show. Back in the 90s, that was a big achievement.”

This was the live set captured on Alive 1997, the duo’s first live album, initially available as part of Discovery’s Daft Club before getting a wider release in October 2001. The album comprises 45 minutes of the duo’s set from Birmingham’s Que Club on November 8 1997; apparently one of Daft Punk’s favourite gigs from the tour, including elements of Homework tracks Daftendirekt, Da Funk, Rollin’ & Scratchin’, Revolution 909 and Alive. (As well as a smattering of Armand Van Helden’s “Ten Minutes of Funk” remix of Da Funk and a tantalising glimpse of the synth stabs from Short Circuit, which would turn up on Discovery four years later.)

French music has always carried a waft of romance with it. From the classical to Serge Gainsbourg, George Delerues, and SebastiAn (with Charlotte Gainsbourg), there have always been measures of romance. Such is also the case with Daft Punk.

When the band moved from Homework to make Discovery. It’s not odd for bands to make a sophomore that sharply contrasts their first, but this one is special in other ways. We must remember that One More Time was slated in British music press:

Daft Punk fans, it appeared, didn’t like being reminded of Cher. One More Time was slated in the dance music press for being derivative and selling out the Daft Punk tradition in search of commercial success - BBC Radio One DJ Pete Tong memorably compared it to Kool & The Gang – leaving Bangalter to defend the song in the media.

“Autotune is great for fixing vocals, but we use Autotune in a way it wasn’t designed to work,” he told Remix magazine. “A lot of people complain about musicians using Autotune. It reminds me of the late 70s when musicians in France tried to ban the synthesiser. They said it was taking jobs away from musicians. What they didn’t see was that you could use those tools in a new way instead of just for replacing the instruments that came before. People are often afraid of things that sound new.”

Other than that: guitar solos? This was before hyperkinetic rawk-cum-electronix bands like Justice came. This was a cocky step into what the band called the result of growing up, ages zero to ten: Japanese cartoons on TV, van Halen solos, although carefully handled and channeled by the band.

There’s much to say for bands that don’t interact much with journalists. Cardew has cared for this and created a book that is a bit hyperkinetic, interesting, and informative. If this book were a record, I’d say it would sound like Soulwax covering Daft Punk.