Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

When I was thirteen years old I discovered music. I mean, I truly discovered music. Before I entered that very exploratory age, I listened to what my friends listened to, which was what happened to be on the radio. I didn’t care about changing stations if something didn’t specifically catch my senses. I didn’t care about music other than liking to nod my head to it when a tune was catchy.

Then, I heard Depeche Mode just as their masterpiece, Violator, was being released, and I wholly enirely changed my focus: I went deep into music and lyrics, and far beyond Depeche Mode.

In my mid-teens I listened to synth-based music a lot, mainly because I had older friends who only listened to that stuff. Howard Jones. Tangerine Dream. Soft stuff.

I found friends my own age and went to clubs where Front 242, Nitzer Ebb, and Einstürzende Neubauten drew me in. I tried listening to stuff like Throbbing Gristle but in spite of liking their do-it-yourself style, I couldn’t find anything redeeming in their music: it was too coarse for me, a youth who couldn’t stand listening to Kollaps, the first album that Einstürzende Neubauten released.

Throbbing Gristle were worse. They used basic instruments and didn’t seem to be interested in playing them in any ordered way. They were also political and I couldn’t bother with politics back at a time when I only wanted to hang out with mates and get drunk.

Today, things are different. I’m a middle-aged whitey who’s listened a fair amount to Throbbing Gristle and their experimental ways.

I enjoyed Cosey Fanni Tutti’s autobiography, Art Sex Music, which painted a very detailed, vivid, and exploratory picture of a human and artist who’s always been interested in fun, profundity, the shallow, and the serious. And a lot of stuff in-between. So, her memoirs are filled with much detail and candour, it seems.

She wrote of her meeting Genesis P-Orridge at a young age, about moving in together, about experimenting through life, different dimensions, mind-expanding and mind-altering escapades that changed not only their own lives, but the lives of the people around them, not least through their now-legendary band, Throbbing Gristle.

Cosey’s autobiography tells of Genesis’s gaslighting and terrorising her, beating her, threatening, and psychologically caging her for years. She recants where he ran after her with a knife as she physically was moving away from him.

This is my review of Cosey’s book.

Genesis’s book is very different to Cosey’s. They were very different individuals while they share several loves, including themselves. They were happy, at points, before everything broke apart. Before they, as a band, splintered.

When reading Genesis’s book, a quote came to my mind: ‘You don’t gotta burn the books/You just remove ’em.’

Genesis does not mention much of why Throbbing Gristle broke up, but instead paints a picture of other band members who don’t want to go to new places like they did.

I knew she was seeing Chris, because we were all together. And that didn’t bother me at all. It was just par for the course. I was seeing Soo Catwoman and was having an affair with a Japanese journalist named Akiko Hada. And then I had Kim Norris on top of that. I had three girlfriends who were all really fun, and everything was fine.

Then Cosey finally said, “I think I don’t—I don’t think I—I don’t want to live here anymore. I don’t think I’m in love with you anymore. I think I want to move out and be with Chris.” “Oh, okay.” Then we talked a little bit, and she said, “I’m going to go away on my own for about two weeks, and then I’ll try and decide who I want to be with.” “Oh, okay. Okay.”

Off she went, and every day or two I’d get a postcard. It would say things like, My darling Gen, I miss you so much, or I’m so lonely, all this lovey-dovey stuff. Those came about every three days. Then she came back and she announced, “I’m gonna live with Chris.” “Ah, okay.” I cried a bit, because I felt that I had fucked up the COUM thing. And, of course, I was attached to her—I did love her. Somehow, within a day or so of that, however, I found out that Chris had gone with her on the trip.

So the whole time she’d been writing these bogus postcards, she was with Chris. I thought, Why didn’t you tell me? Why did she have to keep lying and make up this deception? Especially after I’d already said okay? Ultimately, Cosey wanted the car, the stability, a family—something much more domestic. There was no stability in my vision. That definitely bothered her.

I remember clearly a point when Cosey told me probably one of the truest things she ever said: “Sometimes, I feel like I’m just dissolving in you, in the intensity of what you are. I’m just vanishing into it. I’m drowning in it.” Larger-than-life Genesis just sucked her in, and she didn’t want to be a puppet anymore. She couldn’t deal with it, didn’t want to, which was fine. That wasn’t what I was asking, but that’s how it felt to her. She made the right decision to go. I just wish she’d have been more honest. That was when it broke, in 1978.

According to Cosey, there is far more to the legend of Throbbing Gristle, and her relationships with Genesis, than what is quite vapidly described in Nonbinary. Cosey wrote dozens of pages about band troubles, how Genesis rarely showed up or cared about correspondence, other than that relating to legalities. Money changed everything.

On the other hand, what is not as vapid, are Genesis’s descriptions of everything else: their meeting William S. Burroughs, their idol, is intriguing:

“Can you reach that book on top of my desk,” he said, lifting one trembling hand and pointing at a leather volume filled with strange bits of paper. I picked it up and started to hand it to him.

“No, open it,” he said. I opened the book, and the first thing I saw was the photograph of a flame-throwing soldier cut out from a magazine and glued right next to a girl kneeling in front of a box full of puppies, which was cut and glued so that it fit neatly against the gleaming wing of an airplane. There it was, right in front of me, the same technique that had inspired me to leave behind all the tried-and-true ways of doing things.

I turned page after page in the book, some of the collages so freshly glued that a piece of newspaper fell out of the book. I apologized and started pasting an image of a bloody corpse back where it belonged. “You’re being too careful,” he said, taking a long sip of whisky. He tossed me an old magazine.

“Find an image you like and stick it there instead.” I turned a few pages of the magazine, ripped out an ad for Harrods, and patted it onto the dots of glue. “Now you’re learning from the master. But I’ll have to ask you to do something in return,” he drawled. My mind sketched out several possibilities.

The one thing about William that would forever be true was that I never knew what was next. That was the most amazing thing about him. He was a living example of cut-up technique. “What is it?” I said, closing the book of cut-up collages, rubbing a bit of glue between my forefinger and thumb.

“You can get me another drink,” he said, holding his glass high in the air. “And one for yourself as well.” “I still have a little,” I said sheepishly. “To meeting interesting people,” he said, nodding at me to finish what was left. “I thought you’d have kicked me out by now,” I said, finishing the rest in one wincing gulp. “I think you’ll last a few more minutes,” he said. “I’m quite optimistic about that.”

He turned to me at the front door to his building and smiled, a wonderfully sincere and warm smile. Then he spoke, gently but firmly, my ferrets still around his neck. “Genesis …,” he said. “Yes, William,” I answered. “Genesis … your task from now on is to tell me … HOW DO WE SHORT-CIRCUIT CONTROL?” His question that drunken afternoon resonated with me because it had already haunted me.

I feel it’s hard to know what is true and what is made up by Genesis. I can’t say what is factually true, but reading this book, I felt there are a lot of books removed; There always are, as books are almost always too finite to paint a picture of a person; I mean Genesis seems to have been a deceptive person, judging from statements by several people who have been close to them, including former band members.

There are sparks of beauty in this book. Genesis carries a dry sense of English humour that I love:

Just as my interest in the burgeoning youth culture and the inspirational tsunami of radically new pop and blues music was taking off, my family moved to Solihull, the most sterile place in England. I had to leave all my friends, my mod aspirations, and, perhaps toughest of all, my sense of belonging good-naturedly to my peer group. Solihull is a small suburb near Birmingham in the industrial wasteland of England’s Midlands. To this day we recall that whole conurbation as a decaying and deprived toxic dump. But in greater Birmingham, Solihull was where you went if you were successful, a classic dormitory town—a middle-class-wanting-to-be-upper-middle-class dormitory town.

When I answered, “Here, sir,” everybody began pointing and laughing at me. There then followed a few minutes of teacher-led verbal abuse that centered around my English being unintelligible because I had a strong Manchester accent. The core of the ridicule included “Why don’t you go back?” and “What is a pleb like you doing here?” And, of course, attacks on my being a scholarship boy, because my parents were too poor to pay.

I often say that Solihull School taught me who my enemy was.

His story of stabbing – and later befriending – his worst bully at school is ridiculous fun, as is his painfully weird story about meeting his idols, The Rolling Stones, at a young age.

He also describes finding out about William S. Burroughs, Brion Gysin, The Velvet Underground, Pink Floyd, and sex.

There’s a bit of unveiled power throughout some of his more standalone paragraphs:

Changing names is a really potent form of magic. It’s a technique for shedding a nostalgic connection to bloodlines and familial responsibility. Of course, you can also say, “Now I’m going to build my own story, independent of what’s been fed to me, what we’re told we’re supposed to be responsible for, who we’re supposed to respect.” Take all of that out and then try to build your fantasy person and make it a reality.

The godsend for everyone in Britain was the dole, which I hadn’t thought of or known anything about when I left university. But a friend of Cosey told me about getting the dole. And the Hells Angels did it, too: they used to talk about “going to the bank on Monday.” “What’s the bank?” “Oh, it’s the dole. We go down and get our money and that’s it for the week.” “Could I get that, too?” “Yeah, of course.” So I went down and signed up. This was around the middle of 1970, just when the first Ho Ho Funhouse was disintegrating. It was only around three pounds a week, but it was enough.

I also found beauty in their letter-writing:

I started writing to people around the world. One of them was Anna Banana. She was a Canadian artist who listed her image request as “anything to do with bananas.” Her lover was a guy called Bill Gaglione, and the two of them moved to the Bay Area and nicknamed themselves the Bay Area Dadaists. They started doing re-creations of the Cabaret Voltaire from World War I, and the Dadaists’ sound poetry and futurist events. In one of her letters to me she wrote, “We met this really horrible awful man, Monte Cazazza. We were at somebody’s apartment and he came in wearing a dress, really crazed, carrying a little briefcase. He opened the briefcase and there was a dead cat in it, road kill. Then he sprayed cigarette lighter fuel on it and set it on fire, and pulled out a great big magnum revolver and told us we couldn’t leave the room. The smell of burning flesh filled in the room and then he left.”

And, of course, I first met William S. Burroughs through mail art when, much to my surprise, I found his address in FILE, under a listing seeking “Ideas and Camouflage in 1984.” He was living very quietly at the time—he’d become almost invisible. Most of his books were out of print, and though The Wild Boys was soon to be published, he was in a kind of backwater with his career. He hadn’t started doing lectures and readings at that point. He made extra money writing columns for different magazines, including International Times, Penthouse, and other soft-core porno mags. He was struggling. From then on, Burroughs and I kept writing back and forth regularly. He sent me postcards from different places. He had a lot of postcards of the British Museum. He had postcards of different shamanic things that he was obsessed with at different times. One year he sent me a little bundle of postcards, tied in a little ribbon, as a birthday card, which was really sweet.

Their writing about how Throbbing Gristle was a reaction to everything that came before them is both inspiring and enthralling:

We did another show with mirrors in front of us so people who wanted to listen could only see themselves. We once played behind a screen and they threw chairs at the screen and tried to push over the PA, and there was a big fight. To this day, it doesn’t really make sense to me that people are so addicted to seeing the making of the sound. Why does it matter? Why do you have to see it being done? But it’s an addiction, and when we’re breaking systems, you have to break all of them.

There’s a lot to be said about their writing about musical genres and barriers overall:

At the time, there was a big split in Britain between punk and what we called industrial. There was that classic quote about punk: “Learn three chords and form a band.” But I thought, Why learn any chords? That was the difference. Why learn any chords? As soon as you learn chords, you’ve surrendered to tradition. We weren’t trying to please anyone except ourselves, and if we were confused by it ourselves, even better.

In these matters, it’s exciting and freeing to read Genesis’s thoughts. On the other hand, to myself, it bears a reek; I believe what Cosey has written about Genesis’s abuse. What I believe is the truth has made Genesis into a rancid liar and this book is the product of that person.

Genesis are dead, unable to defend themselves. On the other hand, they didn’t defend themselves against the accusations when Cosey’s book was released, other than stating that Cosey was lying.

This book reeks.

It’s a shame. Genesis has done a lot of good things in the form of art. Yet, this book feels manipulated, lacking a better word. Sure, all artists and humans are manipulators, but this book gives way to a lot of friction.

Viscerally, I feel that there is a lot to be said about a book that starts off vivaciously with a story about a drunken ramble with one of my literary favourites, William S. Burroughs, but there’s far more to be said about a person who won’t indulge with their disgraced legacy for even a second. It’s all a bit cloak and dagger, smoke and mirrors.

There’s a lot of stories and a bit of name-dropping in this book, especially after Genesis moves to the USA. Their stories about meeting and loving Jacqueline Breyer are heartfelt.

If there’s something positive to be drawn from this book, it’s the Burroughsian quote that lasts from the first to the last page: short-circuit control. It is what Genesis held on to and should be at the heart of any artist worth their mettle, if that mettle is worth more than pewter.

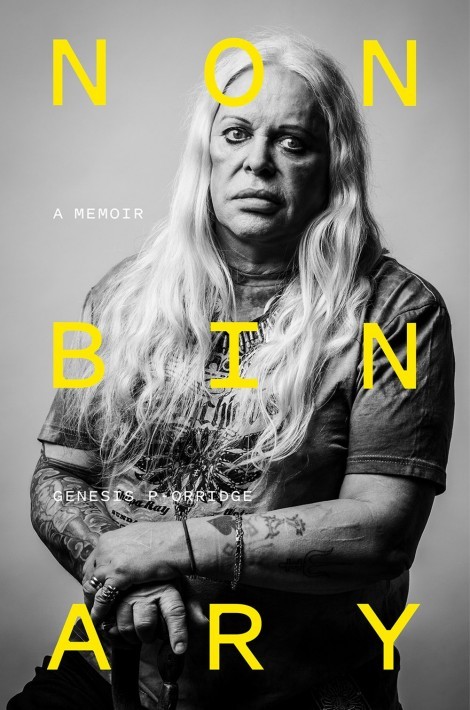

Nonbinary is released by Abrams Press on 2021-06-15.