Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

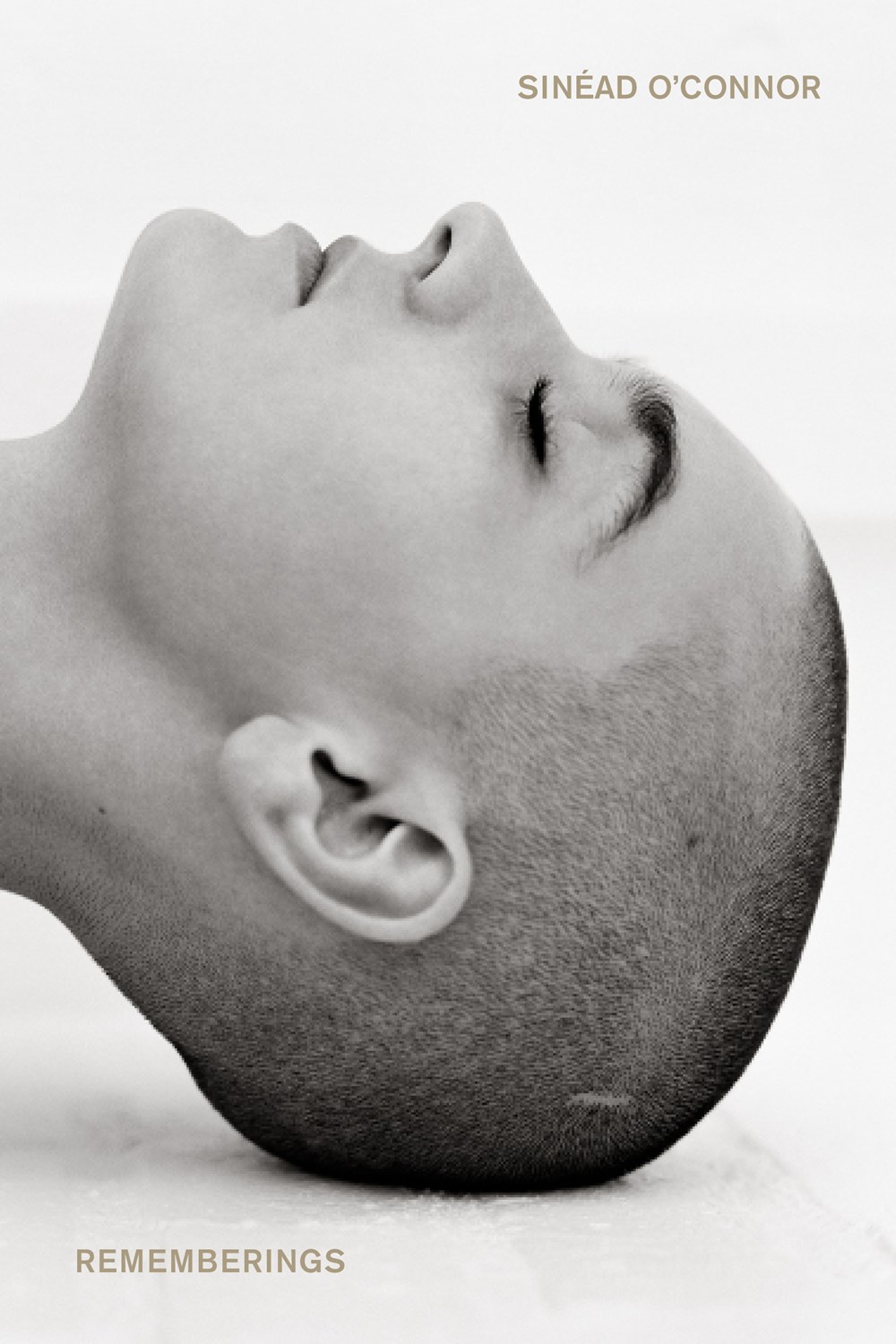

Firstly, I will state the obvious: Sinéad O’Connor is one tough motherfucker. She is also a talented storyteller, as if that needs stating for anybody who listens to her music.

I don’t. I don’t listen to her music. I find her voice lovely but I don’t like her music particularly.

Her stories, the collected writings in this book, however, I have much time for.

I can’t remember any more than I have given my publisher. Except for that which is private or that I wish to forget. The totality indeed of what I do not recall would fill ten thousand libraries, so it’s probably just as well I don’t remember. Chiefly I don’t remember because I wasn’t really present until about six months ago. And as I write this, I’m fifty-four years of age. There are many reasons I wasn’t present. You can glean them here. Or most of them. I was actually present before my first album came out. And then I went somewhere else inside myself. And I began to smoke weed. I never finally stopped until mid-2020. So, yeah, I ain’t been quite here, and it’s hard to recollect what you weren’t present at.

This is a typical example of how she writes: it’s no nonsense, and very different from the American textbook approach, where you get paid by the word. I wish this book were longer, but I just hope O’Connor writes another book.

That said, the contents of this book are remarkable, not at least because of her upbringing. Her mother seems to have been a Hellion, someone who should not have been responsible for children. The abuse that O’Connor writes of is beyond diabolical, and her punchy language adds flavour to what must be a story of survival.

Part of what makes O’Connor’s writing about her youth extraordinary is that it exists in the present: she is there and we see what she saw back then.

We had gone to Lourdes via a travel agent. Picked up at the airport by a tour bus. We drove with about twenty other people who were on our tour. We didn’t do just Lourdes; we first went to a town called Nevers to see the convent where Saint Bernadette lived and died after her visitations from Our Lady. They had her tiny body in a Snow White glass case on display, and people filed in there every day to see it, a grotesque tableau. It reminded me of the Dublin zoo. They had a crocodile in a glass enclosure the exact length and width of its body, so it couldn’t move, with enough water to almost cover it while leaving its back exposed. At the top of the glass there was a gap with the ceiling. The grown-ups would throw coins through the gap so they’d land on the crocodile’s back to see if they could annoy it because it couldn’t move. I wonder what the zoo people did with all the coins.

Paragraphs like this one turned me to stasis, frozen in utter isolation with some of my worst visceral sensibilities from childhood:

Mrs. Sheils, who was a teacher, used to ask me if my mother made me do it but I said no. She’d ask me where the welts on my legs came from or about the massively swollen black eye I once had. She’d say, “It’s your mother, isn’t it?” But I’d deny it. If my mother found out I’d told, she’d murder me. I felt bad lying to Mrs. Sheils because she’s lovely. I don’t know why she likes me, but she does. I’d like to be her girl. I’d like to be going home with her every afternoon. She’d look like she was about to cry whenever I said it wasn’t my mother. Her face would go all red and she’d reach deep into her handbag and give me money for sweets and pat my face all gentle like my granny does.

Then, there’s this:

I’m jealous when I see the other girls walking down Merrion Avenue after school with their mothers’ arms around them. That’s because I’m the kid crying in fear on the last day of term before the summer holidays. I have to pretend I lost my field hockey stick, because I know my mother will hit me with it all summer if I bring it home. But she’ll just use the carpet-sweeper pole instead. She’ll make me take off all my clothes and lie on the floor and open my legs and arms and let her hit me with the sweeping brush in my private parts. She makes me say, “I am nothing,” over and over and if I don’t, she won’t stop stomping on me. She says she wants to burst my womb. She makes me beg her for “mercy.” I won the prize in kindergarten for being able to curl up into the smallest ball, but my teacher never knew why I could do it so well.

From a very early age, O’Connor finds music.

Against the wall rests an old piano. The keys are yellow, like my granddad’s teeth. There are echoes in the notes, a strange sound, like the ghost bells of a sunken ship. I sneak in here often by myself because the piano summons me.

At the best of times, O’Connor’s writing immediately brought me there, to the place she describes. Few writers can do this, immediately transport you to a place and time with just a stroke of the pen. Herein lies O’Connor’s greatest strength, paired only by her humour.

I love the Sex Pistols. I love “Anarchy in the UK.” And “Pretty Vacant” and “God Save the Queen.” And I love the Boomtown Rats and Stiff Little Fingers. All the screaming, I love that. In real life you aren’t allowed to say you’re angry but in music you can say anything. I love all the noisy electric guitars. My brother played me a Bob Dylan song called “Idiot Wind.” It’s really angry and he says loads of mean things to someone. It’s really brave. He isn’t pretending to be nice all the time.

I loved reading about the beauty that she saw in music:

One night a band called the Fureys played a gig downstairs in our little concert hall. We girls were allowed to attend. They played my favorite song, “Sweet Sixteen,” which always makes me think of my first love, B. I had to leave him when I came here, him and all my other friends. But then they did an instrumental piece, played on a sort of high Irish whistle, that they said Finbar Furey, the lead singer, wrote when he was twelve. It was called “The Lonesome Boatman.” The most beautiful and haunting melody I’ve ever heard. Such grief to have come from a child. It was like he knew my own heart. And no one in this place had ever known my heart. I waited behind when the audience left and the band was packing up. Walked up to Finbar and told him he’d made me want to be a musician. I’m friends with him now (at fifty-three years of age) and he doesn’t remember meeting me. But I will always remember meeting him. And to this day, if I so much as see his name on a dressing-room door, as I sometimes do when we are doing the same festivals, I cry. Just because his music and his songs are so beautiful.

To rebel, to oppose injustice, I think, is not at all O’Connor’s biggest characteristic. She creates art and expresses herself. It’s just that people aren’t used to others speaking out; some are, possibly, especially incensed by women doing just that.

I think O’Connor’s mainly spoken out against oppression because she had to, much like Simone Weil communicated that we must react to some immediate injustices.

My mother said we’re not allowed to like my stepmother. When we’d go driving through town, she’d point out shops where she said my stepmother buys clothes and say, “Only hooers go there.” She’d point out hotels and clubs, too, and say the same. It made me and my sister laugh and want to go to all those places. She said, “Only hooers pierce their ears,” so I got my ears pierced a few days after I left her. Got my hair cut real short too because “only hooers” do that.

On sharing a room with her sister:

For one reason and one reason alone, it was hell sharing that bedroom in my father’s house with her: she was in love with Barry Manilow. So her side of the room was papered with massive posters of him while mine was all Siouxsie and the Banshees. Each of us woke in hell, I would imagine, if my posters scared her in the night as much as her talking about Manilow in romantic terms scared me.

Joe plays guitar. He says he doesn’t play well, but he does. My sister plays harp and my younger brother plays drums. I always thought it would be brilliant to make one album together and call it Fuck the Corrs. But the fights would have made Liam and Noel Gallagher seem like pussycats.

Every paragraph of fun can be like an Alice Munro short story; they’re fairly short and just tell it like it is. We’d have a lot more time on our hands if we’d only follow O’Connor’s way of writing in a lot of other ways.

Then there are paragraphs that make everything that is family:

Once when we were teenagers, John and I went to the cinema to see the horror movie Halloween. The murderer was wearing a white hockey goaltender mask. Afterward, John chased me all the way up O’Connell Street with his white motorbike helmet on backward. How he didn’t bash into anything I’ll never know. He scared the bejaysus out of me. Once I bit his nose during a pretend fight. The clever fucker snotted into my mouth. We really are a very messed-up family. We don’t even suit that word, family. It should be a comforting word. But it’s not. It’s a painful, stabbing word. Cuts the heart into pieces. And all the more because it’s too late to go back and do anything differently.

I loved this bit from after O’Connor had signed her first record deal and went to London:

I vividly remember getting into a fight with a skinhead outside a red phone box. An East Asian woman was inside, spilling out a million words in some exotic language quick as she could because she had only a few coins. The skinhead dude was yelling at her to hurry up and he started banging on the door, though I was next in the queue. I said he should leave her alone. He detected I was Irish and yelled at me, “London phone boxes are for London people!” I said, “Well, if you lot had left us a thing of our own in our own countries, we wouldn’t need to use your manky phone boxes with their stickers of hooers everywhere, so shut the fuck up.” Three of his friends were in the queue, and I think I’d have got my face broken if they hadn’t started laughing at him because he’d been out-argued by a girl, and, thank God, for pride-saving alone, he had to pretend he saw the funny side. I got to make my call and they all shook my hand when I was finished, then stood back on the path to make way for me like I was Bishop John McQuaid in Dublin imperially strutting down Grafton Street on Christmas.

When pregnant:

I got thrown out of an Italian café in Charing Cross last week by the old lady running the place because I had on, cut short so that my bump was exposed, a white T-shirt on which was printed ALWAYS USE A CONDOM. She wasn’t seeing the funny side.

I go into the record shop and ask the old man what part of the Bible such-and-such a song he played is from. I have a notebook with me that I take everywhere. I write down what he tells me, then I go home and read the passages. He finds me amusing, I think. He smiles at me so nicely; his face is like a huge sun shining. He says, “What is it today, little daughter?” Anytime I talk to the old men, they call me “little daughter.” If middle-aged men are around, they call me “little sister.” They’re really kind to me. They never mess about. They’re very protective. They ask me if I ate and give me Jamaican patties if I say no. They never mind that I just hang about beside them not saying a whole lot.

Her record-company contacts are, undoubtedly, a bunch of dicks who didn’t care about her; they did, however, care about selling her. Reading O’Connor’s brief words on how they tried to get a doctor to convince her of aborting her to-be firstborn is disgusting, as is how they wanted her to keep her hair.

Me? I loved it. I looked like an alien. Looked like Star Trek. Didn’t matter what I wore now. When I walked through Ensign, I got stunned silence from Nigel. Doreen, with her back to him, gave me a silent double thumbs-up with a playful smile. Chris asked me to sit in the car with him later. “Why’ve yew dunnit?” “Because I wanna be me.” “Cawn’t yew be yew wiv’ ’ayah?” I said, “It’s you who needs hair, you baldy oul fecker, not me. Why don’t you let me help you find a doctor?”

The most frightening assault, apart from those of her mother, are from Prince.

I’ve seen this before. I grew up with it. I know it like the back of my hand. I start mentally checking for exits without taking my eyes off him. I realize I don’t know where I am. I never asked for an address. I don’t know how to find the front door. It’s dark. I don’t know how to find a cab. I’m away off up in some hills very far from the highway is all I know. And it doesn’t look like he’s got me here for cake. He commences stalking up and down his side of the breakfast bar, arms crossed, one hand rubbing his chin between his thumb and forefinger as if he has a beard, looking me up and down like (a) I’m a piece of dog shit on the end of his shoe, and (b) he’s figuring out where upon my little body to punch me for the fullest effect. I don’t like this. And I don’t appreciate it. And I don’t appreciate the assumption I’m easy prey. I’m Irish. We’re different. We don’t give a shit who you are. We’ve been colonized by the very worst of the spiritual worst and we survived intact. Accordingly, when he shouts at me, “I don’t like the language you’re using in your print interviews,” I say, “You mean English? Oh. I’m sorry about that, the Irish was beaten out of us.” “No,” he says. “I don’t like you swearing.” “I don’t work for you,” I tell him. “If you don’t like it, you can fuck yourself.” This reeeeeeeeeaaaalllly pisses him off. But he contains it in a silent seethe.

There are a lot of rememberings in here. The book is, overall, like carefully receiving a hug from one of your favourite people in the world. At the same time, this book is frightening and heartwrenching. O’Connor lays her heart bare and doesn’t try to suffocate her reader, nor does she try and convince people. This is quite rare in biographies, and in life, in general.

This book is a lovely mixture of the good and the bad and I can’t wait for more rememberings to come.

Follow the author on Twitter.