Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

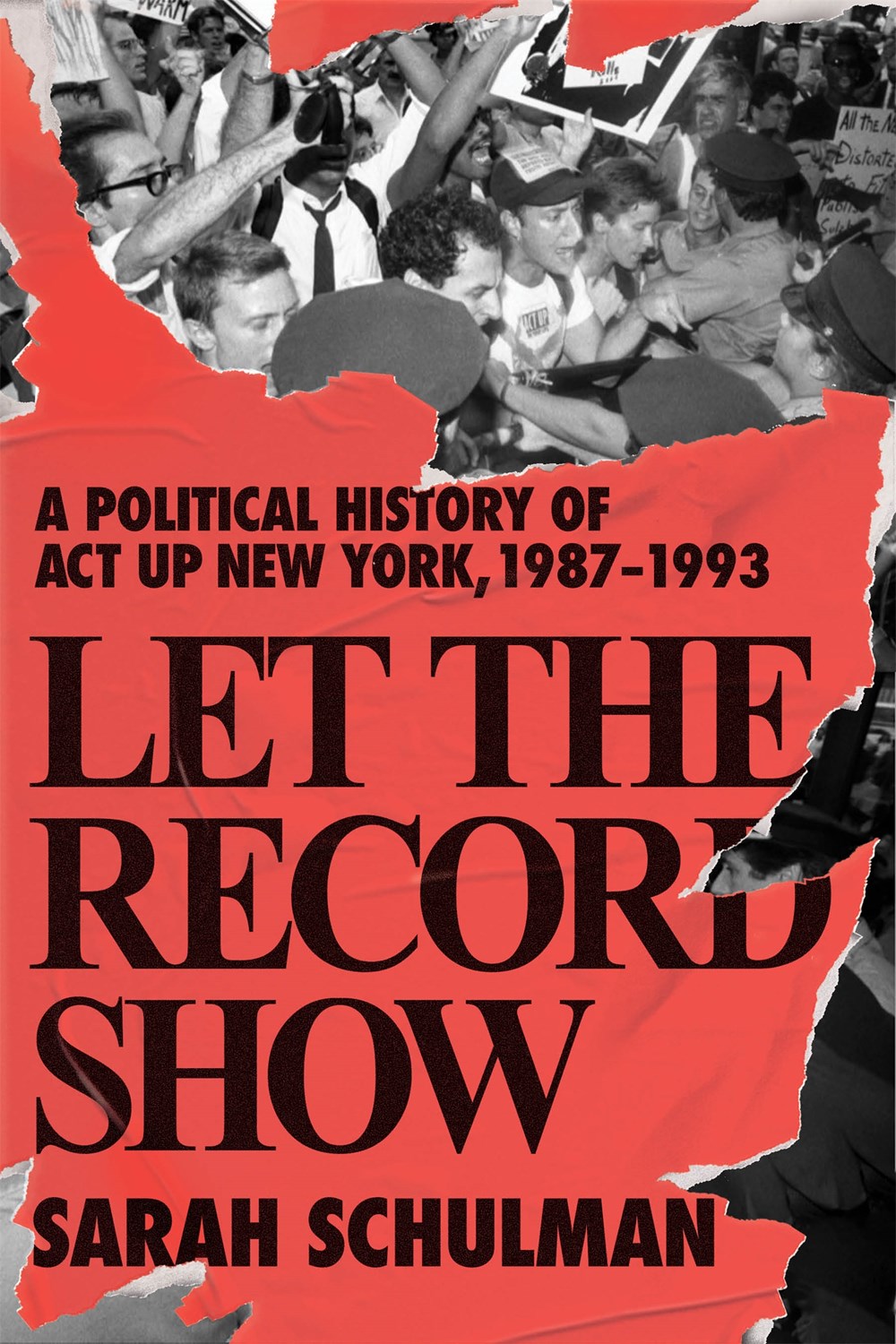

This is not a book that only handles the HIV and AIDS epidemic but an activist guide. It shows hardships, relationships, love, hate, and everything inbetween.

It is a line between what is given and what is taken.

Schulman has created a fascinating and level-headed book that will stand the tests of time and scholarly critique. It shows both humans and statistics, bone-dry deaths and loving depths.

This is, mainly, a book about the individuals who created ACT UP New York, the first of 148 chapters of ACT UP, each of which acted autonomously. This book ranges 1987-1993, but AIDS is not exterminated.

AIDS is not over. Out of the 100,000 New Yorkers who have died of AIDS, 1,779 died in 2017. As of 2019, more than 700,000 people had died of AIDS in the United States, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, including 16,350 in 2017, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. As of 2019, according to UNAIDS, 32 million people worldwide had died of AIDS, with around 690,000 deaths in 2018.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, I heard voices of people living with AIDS. Some of these persons have lived through a pandemic for decades.

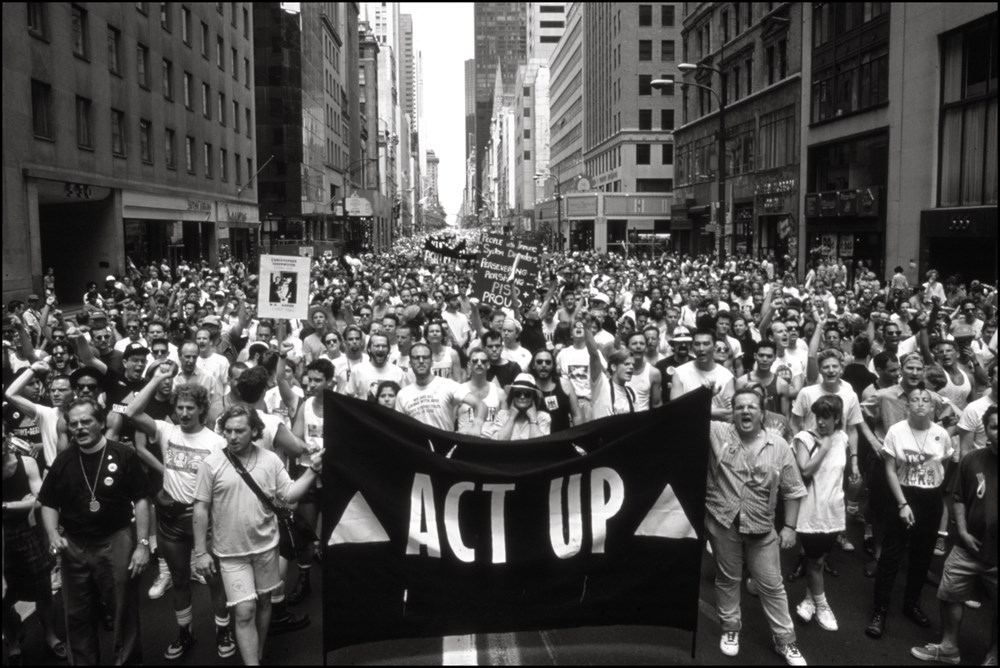

Pride 1989, New York City

Pride 1989, New York City

AIDS prepared us for everything. —JACK WATERS

Schulman gathers these voices and more. She shows how not only homophobia but also rampant injustices and prejudice against people with HIV not only isolated people but caused deathly harm to more people than can be counted.

Angels in America, probably the most lauded American theatrical work of our time, is strangely disconnected from the reality of people with AIDS, relying on the conventional trope of a cowardly gay person who abandons his lover. Interestingly, in a 1992 interview in The New Yorker with theater critic John Lahr, Tony Kushner made no claims to Angels in America being an accurate depiction of the AIDS experience. He explained that the play was—in some ways—about his relationship with his best friend, a woman named Kimberly Flynn, who had had a serious brain injury. Kushner described how he had left her in her crisis.

The guilt of this action of abandonment was the key personal experience at the heart of the play. This actually makes perfect sense, as the use of AIDS in Angels in America is a metaphor, not a central representation. And for that reason it is not reflective of the actual relational dynamics of the time. Coincidentally, this associative impulse produced a work that straight people loved and were comfortable with, and it as a result became iconic and incontestable.

If it had been about straight people abandoning people with AIDS and gay people heroically overcoming heterosexual cruelty to save each other’s lives, which would have been accurate, I don’t know that it would have been so thoroughly praised and elevated. Decades later, in the 2018 book The World Only Spins Forward, by Dan Kois and Isaac Butler, Kushner changed his origin story, saying instead that he had been in love with a dancer who had died of AIDS. But that version resonates less accurately with the play itself, which is not really about love and loss, but instead about fear and abandonment by and of gay men, and recognition and transformation for straight people.

Schulman seems to me not a particularly egocentric person; she displays how not only she but also others have been affected by HIV/AIDS. She is truly great at contrasting movements with the individuals who made them while painting what must undoubtedly have been a painstaking experience in showing how HIV razed not only human lives but entire countries, and I don’t necessarily mean in terms of physical lives.

There are many deaths listed in this book. Many funerals. Despite this, they all have life in common. Sure, most funerals do, but rarely is life in focus as much as in communities, in families, where most of those you know are dying while hated. It’s not strange that Schulman brings up countries, for example, Lebanon and Palestine.

We showed United in Anger, in person, all over the world, including in Palestine, Lebanon, and Abu Dhabi, where Arab viewers learned for the first time that ACT UP had interrupted television broadcasts during the first Gulf War with the slogan “Fight AIDS, Not Arabs.” We brought the film to Brazil, India, and Taiwan—at the time of a bizarre HIV criminalization law prohibiting sex between people who are HIV-positive—as well as all over Europe, and even to Russia, just months after the anti-gay laws went into effect, when members of the dissident rock band and performance art group Pussy Riot had been disappeared into the prison system. People were afraid to come to public screenings, and venues were mandated to post signs saying 18+ ONLY because Russian anti-gay laws were based on fake charges of “corrupting” youth.

There are people with HIV/AIDS everywhere in the world. Just recently Dan Glass and ACT UP London invited me to show the film for the tenth or so time in that city, and again we had a full house: people who had never seen images of AIDS activism, people watching the film for the first time, queer people and people with HIV from Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Macedonia, looking for inspiration, support, and tactics. We made it available for free on Kanopy and YouTube, encouraging high schools and colleges with no budget for buying films to show this work to students for free. And queer studies professor Matt Brim wrote a study guide for teachers, which is available for free at www.unitedinanger.com/study-guide, so that instructors won’t need a background in HIV or AIDS history to be able to share the film effectively with students.

Abortion Rights protest

Abortion Rights protest

This book was extremely fast to read for me. It’s a flight through human conditions. It’s genuinely enthralling and all-encompassing.

The book goes far into capitalism feeds HIV to beat humans:

However, while advocates were able, in a sense, to beat HIV, they could not beat capitalism. And so, today, because of the greed of international pharmaceutical companies and various health industries, large numbers of people with HIV in the United States and around the world cannot receive medications that already exist. For this reason, around three-quarters of a million people throughout the world still die every year of a disease that is entirely manageable. In the United States, infected people without insurance, living in states with no targeted funding, do not have access to the current standard of care because we don’t have a coherent health insurance system. Direct care workers have told me that in New York City today, many AIDS deaths are diagnosed in the emergency room, often because the person had no health care. According to The New York Times, reporting on the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall, “of the 1,790 people who died of AIDS in New York City in 2016, 1,471 were black or Latinx, and more than half were living in extreme poverty. Across the country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC), African-Americans accounted for 43 percent of H.I.V. diagnoses in 2017, though they represent just 13 percent of the population.”

The book contains multitudes of stories of how activists help each other and strangers to get what they need: medicines, laws passed, change through protest, constant struggle against homophobia, fascism, prejudice, etc.

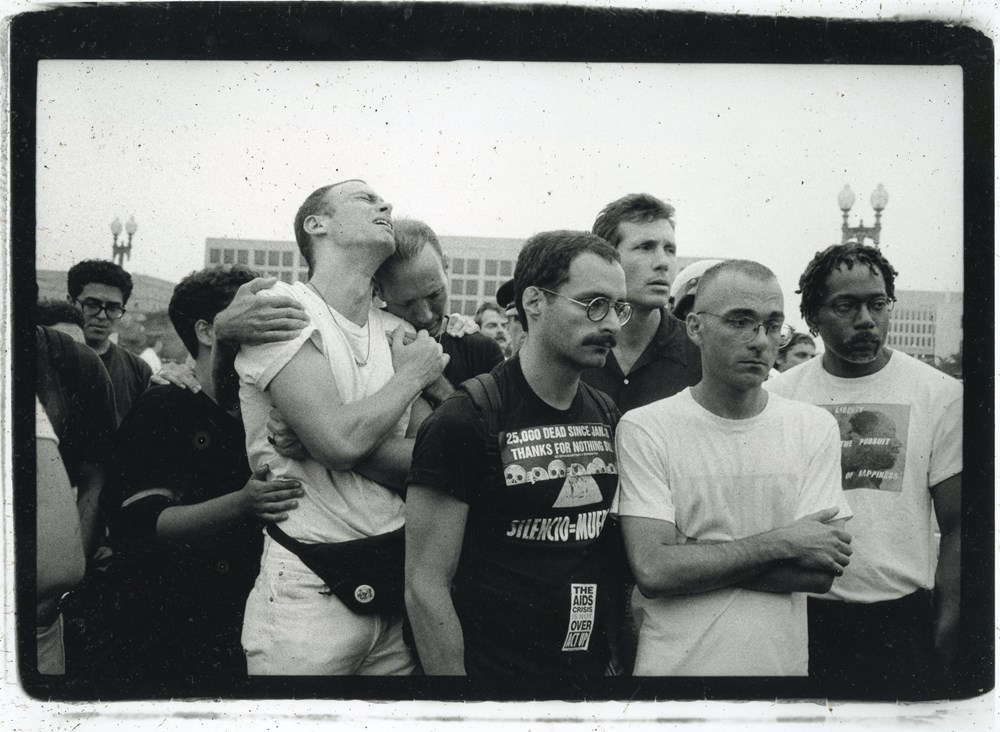

DAVID WOJNAROWICZ’S POLITICAL FUNERAL, JULY 29, 1992 The Marys were in Steven Machon’s apartment, talking about what they wanted to have happen after they died. Burning of bodies on pyres was very high on the list. Tim and John and Mark started to discuss their deaths seriously. They were videotaped saying what their wishes were, and the others promised to carry out their mission. In his memoir, Close to the Knives, published in 1991, David Wojnarowicz had written: “I imagine what it would be like if friends had a demonstration each time a lover or a friend or a stranger died of AIDS. I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour to Washington D.C. and blast though the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.”

ACT UP decided to do a procession from David’s house down Second Avenue, past Tompkins Square Park, through the Village, ending up at the parking lot at the corner, near Astor Place. When they got to the parking lot they wanted to project this slide with text from Close to the Knives: I worry that friends will slowly become professional pall bearers, waiting for each death of their lovers, friends and neighbors, and polishing their funeral speeches. Perfecting their rituals of death, rather than a relatively simple ritual of life—such as screaming in the streets.

Mourners at an ACT UP funeral

Mourners at an ACT UP funeral

Also, the police had detectives that spied and integrated in ACT UP:

MARY DORMAN “They definitely, definitely had detectives in ACT UP … There definitely were snitches. Absolutely … because they were informed about a lot of things. And I know, writing from the Freedom of Information Act for myself, that the FBI has files on me, NYPD has files on me, CIA has files on me. They’re all organizationally affiliated and I know it’s ACT UP … I have a good faith belief that there were undercover police there or informants, whether they were police officers or not. And I do have an idea who it was, but I cannot say.”

Get this book. It is one of the most vital books that I have ever read.

ACT UP Oral History Interviews are available on www.actuporalhistory.org.

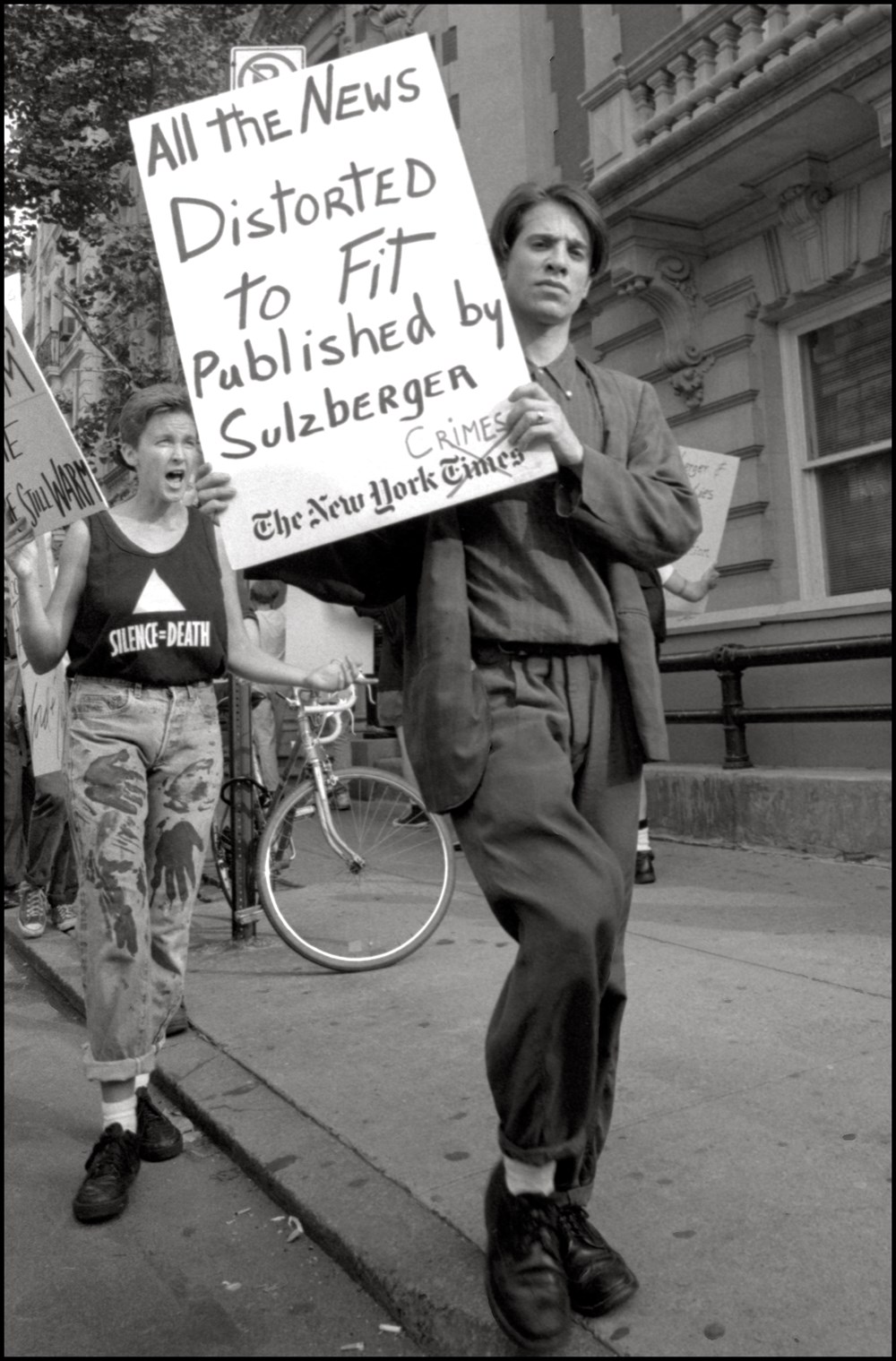

Protesting the New York Times

Protesting the New York Times