Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

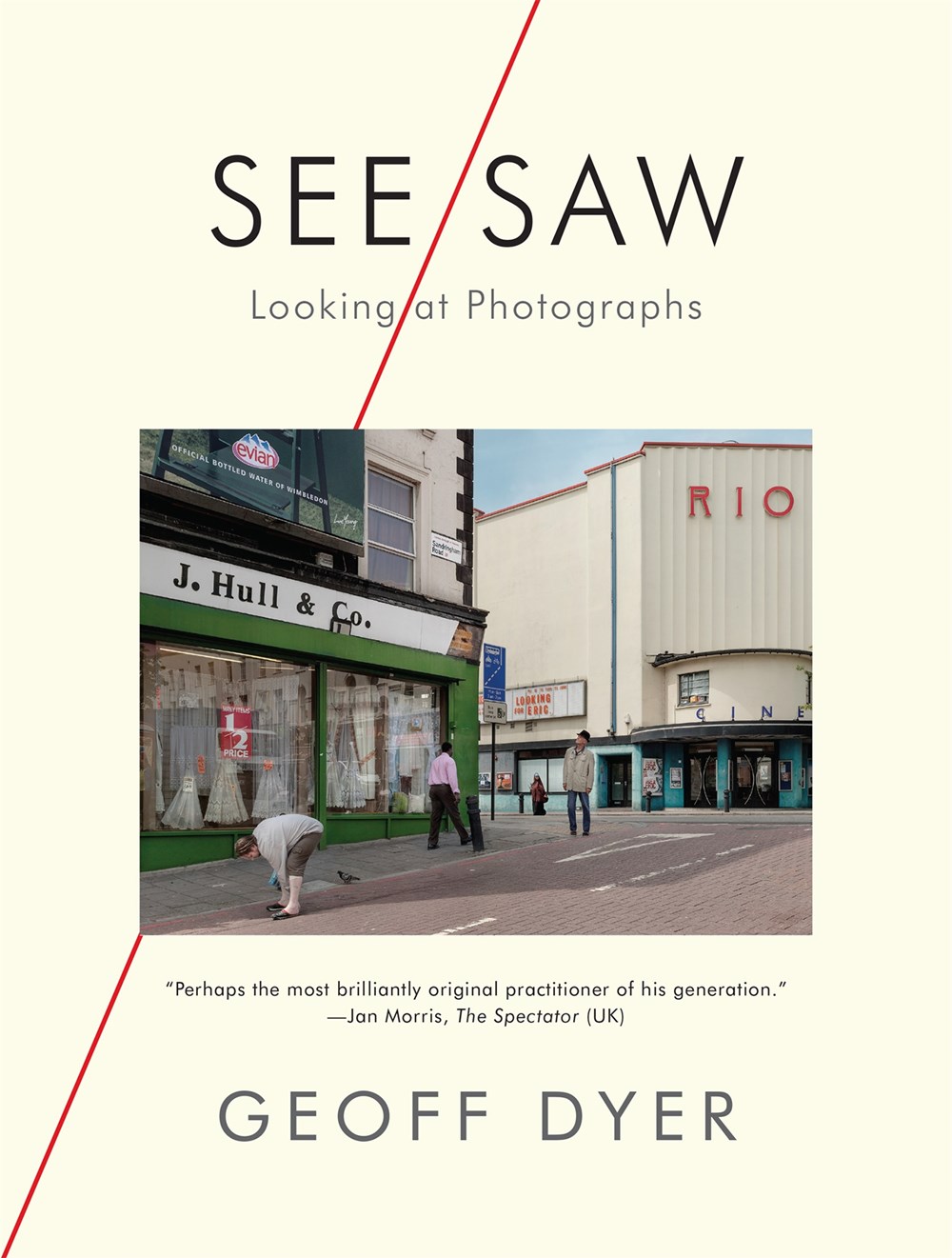

‘I just look and think about what I’m looking at.’

When I read Joe Moran’s excellent First You Write A Sentence I thought about how he reads cook books: he reads them, he does not merely follow their instructions.

Geoff Dyer’s way of discovering photography is similar: he started reading about other people looking at pictures.

This book is entirely filled with his own views on photography. And he does see things.

Dyer is both curious and eloquent. His words on photography are enticing, inspiring, and interesting. He made me look up most of the photographs on the basis of his words, not because of the pictures that are included in this book! That’s really something!

He’s not coquettish about how he does it.

Naturally, I have no method. I just look, and think about what I’m looking at, and then try to articulate what I’ve seen and thought – which encourages me to see things I hadn’t previously noticed, to have thoughts I hadn’t had before the writing began.

Dyer’s style is simple: short sentences, all briefly examining what’s inside their paragraphs.

He likes to quote:

Roland Barthes said photographs were prophecies in reverse, but they can be straightforward prophecies too.

Cartier-Bresson said that the world shown in a picture could be reconfigured ‘by a simple shifting of our heads a thousandth of an inch’.

Four years after the end of the immense cataclysm of the First World War, T.S. Eliot will write in The Waste Land, ‘so many,/I had not thought death had undone so many.’

The quotes does make sense. They take the reader on little rides.

The photographs and photographers do take centre stage, to be sure; this is no dilettante’s quest, no matter how much of a bumbler Dyer tries to stage himself.

Vivian Maier represents an extreme instance of posthumous discovery, of someone who exists entirely in terms of what she saw. Not only was she unknown to the photographic world, hardly anyone seemed to know that she even took photographs. While this seems unfortunate, perhaps even cruel – a symptom or side effect of the fact that she never married or had children, and apparently had no close friends – it also says something about the unknowable potential of all human beings. As Wisława Szymborska writes of Homer in her poem ‘Census’: ‘No one knows what he does in his spare time.’

His writing of some photographs by Dennis Hopper excels what I have seen elsewhere:

usually means ‘not worth publishing in his or her lifetime’. The history of photography, on the other hand, is constantly getting updated and rewritten as entire bodies of work are discovered. Vivian Maier is the most recent and celebrated case: until her photographs came to light few people seemed to have any idea that she had even existed. The same, of course, cannot be said of Dennis Hopper, though for chunks of his life people in close proximity to him – wives, friends and collaborators – experienced that existence as a deranged threat to theirs.

His mania found a perfect outlet, years later, when he invested the role of Frank with intensely psychotic charm in David Lynch’s 1986 film Blue Velvet. Former wife Brooke Hayward (the first of five, the second of whom was only around for two weeks) speaks tenderly and respectfully of him in the book accompanying the 2014 exhibition of her husband’s Lost Album of photographs at the Royal Academy of Arts. She also remembers him as ‘a sweetheart’ in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, but that was before she had her nose broken and became scared that he was going to kill her. Not so Rip Torn who, when Hopper pulled a knife on him, twisted it out of his hand and turned it on his assailant. W.H. Auden wrote that ‘It’s better to be . . . liked than dreaded’;2 Hopper would seem to have been loved and dreaded, especially once his directorial debut, Easy Rider, became a paradigm-busting hit.

Nicely photographed by Hopper as a lobbyist high on the cosmic importance of his campaign, Timothy Leary provided the happy mantra of the 1960s – ‘Tune in, turn on, drop out’ – but the decade’s epitaph was spoken by Peter Fonda in Easy Rider: ‘We blew it.’

Dyer is the kind of writer who wants to make a splash. He does so without completely draining the pool into which he catapults himself. His Id nearly lies in containing and springing the value of his observations: the reader is left with no defense against his little sentences that show us what he thinks, without trying to be smart about it.

There’s vast difference between trying to convey value and sensation cleverly and just trying to seem clever: most writers fail at this.

I’m very glad to note that Dyer is very good at what he does.

The Foreigner’s Road Trip - Robert Frank’s America

The Foreigner’s Road Trip - Robert Frank’s America

Robert Frank’s The Americans (1955–6) offered a radical reconception of what a photograph could be. A beneficiary of this legacy, Hopper didn’t take photography into the realm where content almost overwhelms form, as did Garry Winogrand; he did not have the visual complexity of Lee Friedlander; nor did he have the obsessive eye of Diane Arbus. While he didn’t invent or significantly extend a way of seeing, he was fully articulate in the visual language of the time. As Fonda put it, he had an understanding ‘not just of the frame of the camera but the frame of the life’.

Luigi Ghirri, the Italian master of color photography

Luigi Ghirri, the Italian master of color photography

Another example of a typically well-written paragraph:

Ghirri’s work seems to have a near-universal effect on anyone who encounters it. You see a handful of his images – an empty basketball court, a puddle in a road reflecting a palm tree, a kids’ slide on a beach, a red Coca-Cola flag against a pale blue sky, a view of an Italian countryside that seems haunted by its own ordinariness, an empty piazza that looks like a de Chirico in broad daylight – and fall quickly under his spell. The initial enthusiastic reaction – ‘What a great photograph!’ – gives way, on the basis of only a little further sampling, to the conviction, ‘He’s a great photographer!’ Actually, that might be understating things. E.M. Cioran wisely warned that the further a person advances in life, the less there is to convert to, but even at an advanced state of photographic appreciation you do not simply become an admirer of Ghirri’s work; you become a convert.

In conclusion, this book taught me not only about photography but also of how one can view an image. There are many pleasant things we can say about people who open our eyes, and Dyer certainly did that for me. Thank you, Geoff.