Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

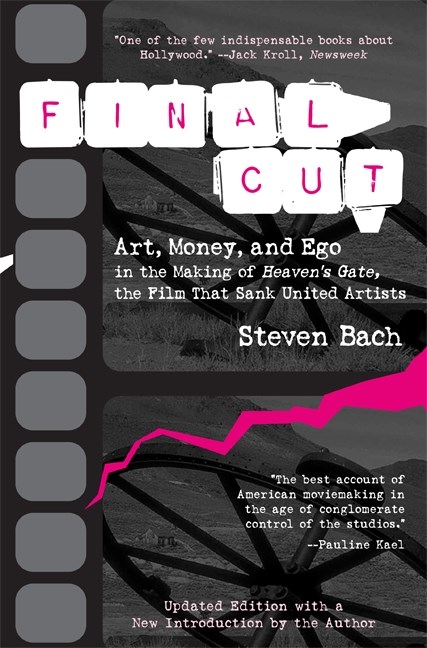

Steven Bach was Senior Vice President and Head of Worldwide Productions for United Artists, a film studio. They made films. They represented a lot of artists - which partly explains their name and their severe apocalypse due to this film - and made a lot of money.

Final Cut follows Bach’s executive-view journey around the making of Heaven’s Gate, a film that grew and would not stop growing until it had swallowed not only United Artists but most of Hollywood as we know it.

What altered Hollywood irrevocably was the notorious 1980 film Heaven’s Gate.

-Irwin Winkler, The New York Times (January 14, 1999)

In 1976, United Artists won its eight Best Picture Academy Award with One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest. It won its ninth with Rocky. They were on a roll.

Some people may diss this book because of several things: it doesn’t really get into the making of the film until halfway, it has to do with boring things like finance and meetings, and they’re right: I diss those things.

However, if we diss the book because of those things, we miss the seemingly mundane that is part of a bigger picture.

It would be like dissing the bureaucracy of World War II: it’s stupid. The Devil is all in the details, and the details are in the mundane, and the Devil is everywhere, in all of us. The details point to why it’s impossible to diss this book.

Having said that, the book does get boring a little too often. It gets into Deer Hunter a lot, the prior film that people truly wanted Heaven’s Gate to imitate and surpass in all ways.

The book is written from the perspective of a very-high-up manager who looks at names and numbers. This book was published in 1999, before the Internet took off. Remember the days before fame and fortune was all there was for big film studios? When they truly gambled on films? This film is written in those days, and one can see why it’s easy to name-drop when film-makers were auteurs more often than today.

And there was dreck.

And there is Heaven’s Gate, the point in time where artistic vision met money and sank completely.

The film cost $44 million to make and made $3.5 million at the box office. to put this in perspective, United Artists had net earnings of $28.8 million in 1978.

On the other hand, the film carries considerable artistic merit.

It’s lovely to read Bach’s recollections of what people thought before the film started. On actor John Hurt:

Hurt had no other pictures scheduled until The Elephant Man in England in October and viewed “playing cowboy,” as he put it, “a lark.” It was a lark that metamorphosed into an albatross.

Bach was at his black-humour best with some curt and terse sentences:

Cimino insisted on weekly expenses of $2,000, regardless of place of work; it meant he would receive $2,000 per week for the expense of living in his own Beverly Hills home for a projected six-month period of postproduction in Los Angeles. This $2,000 per week was to become retroactive to the September deal date. The letter failed to note that agreeing to this point would require a budget entry of approximately $130,000 over and above Cimino’s $500,000 salary. (Nor was it noted that it would take extravagant genius to spend $2,000 per week on living expenses in Kalispell, Montana.)

I love this part that quotes from the legal papers that the director set out during pre-production:

The two important, emotion-inducing clauses were number ten, in which it was stated, “Mr. Cimino has already informed United Artists that he expects the picture to be no shorter than IV hours,” and number two: “Mr. Cimino’s presentation credit shall be in the form ‘Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate’” (or in such other form as Cimino) may designate); Mr. Cimino’s name in such credit shall be presented in the same size as the title, including all artwork titles, and on a separate line above the title, and shall appear in the form just indicated on theater marquees (United Artists to require such treatment in its agreements with exhibitors).”

Putting aside for the moment the fact that no movie company can “require” theaters to do much of anything now that they no longer own them and that “best efforts” is a frighteningly slippery term and concept, the clause was astonishing to UA, for it amounted to making Cimino’s name, for all intents and purposes, part of the title. This was not keeping up with the Hollywood Joneses; this was keeping up with the Kubricks and Leans.

Stanley Kubrick had had a similar title treatment on A Clockwork Orange, the title of which read—to the not very rib-tickled amusement of Anthony Burgess, who was under the impression he had written the book—Stanley Kufinck’s A Clockwork Orange. All the recent David Lean pictures had been preceded by the words David Lean’s Film of. Kubrick was guilty of usurpation of credit in many industry eyes with this possessory title, but in his defense Spartacus, Lolita, Paths of Glory, Dr. Strangelove, and 2001 (among others) were invoked to justify the hubris. Lean, as already noted here, was perhaps the most consistently successful commercial director in history. Michael Cimino had made two movies, which had been nominated for, bur had not yet received, Academy Awards. Kubrick and Lean between them accounted for thirty-eight wins. Hubris was one thing; this looked like self-apotheosis.

From the very start of filming, things went far without any kind of stop. Warnings were wafted away.

Thousands of feet of film, then tens of thousands, then hundreds of thousands of feet of film were running through the cameras, recording and rerecording images until they were as perfect as technique, patience, and money could make them. There was no chaos; there was its opposite: a calm, determined, relentless pursuit of the perfect.

Cimino was shooting a daily average of 10,000 feet of film (slightly under two hours’ worth) to cover a daily five-eighths of a script page, resulting in a daily minute and a halt or so of usable screen material, and was spending nearly $200,000 a day to do so. Kavanagh pointed out that in spite of all the discussions of “shakedown period” and “catching up on time,” these figures had varied hardly at all from the first day of production through May, and now into June, on the twenty-second of which Cimino’s original schedule had predicted an end to principal photography.

The payroll hill for the first week of June was neatly typed out: $607,356.76. This amount included payments to 1 director, 1 star, 68 supporting players, 177 crew memhers in Montana, 153 crew members in Idaho, 147 crew members imported from Los Angeles, and 57 extras. Above and beyond these costs for more than 600 people were the fringe benefits, housing, food, and the cost of actually making the picture.

It’s utterly amazing to see that Cimino wanted to make a film that was 5.5 hours long and expect to get away with it, considering what was going on. He - and cohorts, make no mistake, one can not blame him for this debacle as he did not just make money appear from nowhere - firmly twaddled himself into a corner much like a child with crayons, just dawdling away at something for far too long.

It all reminds me of how some artists are at their best while restrained. Sure, the Kubricks of the world did produce worthwhile stuff over years of work, but not even Kubrick managed to squander money.

All art is knowing when to stop.

—Toni Morrison, quoted by Carol Sternhell in “Bellows’ Typewriters and Other Tics of the Trade,” New York Times Book Review (September 2, 1984)

Finally, Joann Carelli turned in her sear in front of me and said, laughing, “Do you believe it? It’s over.”

Not for another three hours and thirty-nine minutes,” I said.

She smiled back. “Yes, it is,” she said consolingly. “It’s over.”

Bach succinctly points out the main problem of Heaven’s Gate:

The larger failure of Heaven’s Gate is not that the “golden string” finally stretched to an irrecoverable $44 million (the figure at which it was written off, including promotional costs) but that it failed to engage audiences on the most basic and elemental human levels of sympathy and compassion, and this failure is finally cardinal.

It’s a deeply human film, as is this book, a major executive’s review of an utter horrorshow that shows what everybody knows: that there’s always good with the bad.

To conclude, in Bach’s own words:

In one two-week period in the summer of 1984 the top managements of three major motion-picture companies changed personnel completely. Within three years of the Heaven’s Gate debacle, with only one exception noted below, the management of every major company in the motion-picture industry had changed. Not one production head in Hollywood today is where he was three and a half years earlier. Such instability precludes continuity and development not only in the industry but in “the art form of the 20th century” itself, and one might fairly ask how discipline and responsibility can be expected from artists who know that the only continuities in the business are those of their own work and those derived from conglomerates who, for the most part, own Hollywood and are not, as we have seen, afraid to walk away.

But continuity of the art depends on discipline of the art, because without it, it could fade away. Ultimately what one loves about life are the things that lost, because those who care, see to it that they do. Movies might.