Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

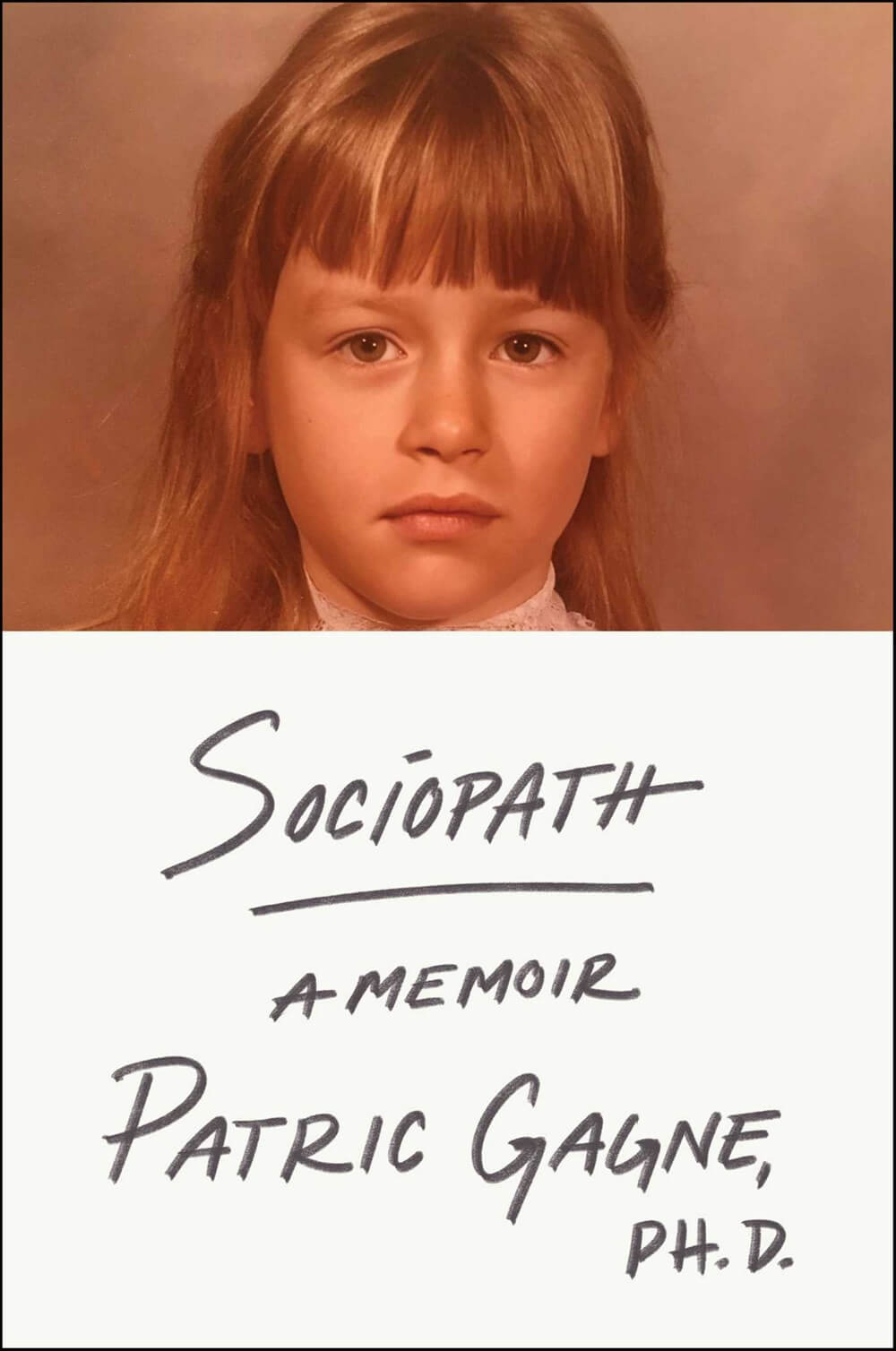

The first thing that caught my eye about this book is that it’s written by a therapist. The second thing is that the term ‘sociopath’ isn’t recognised by big and professional diagnosis tools, for example, DSM-V. The author somewhat addresses this:

The word “sociopath” was introduced by the psychologist G. E. Partridge in 1930, who defined the disorder as a pathology involving the inability to conform behaviorally to prosocial standards. In other words, these are people who don’t act in ways beneficial to society and, rather, intentionally provoke discord. Subsequently, sociopathy was added to the first version of the DSM in 1952. With the publication (and popularity) of the fifth edition of Cleckley’s Mask of Sanity in 1976, however, the term “psychopath” became a catchall for both disorders. But because there was no official changing of the guard concerning the name, researchers and clinicians continued to use psychopath and sociopath interchangeably. This led to a great deal of disagreement in terms of diagnostic criteria and general understanding.

The following paragraph is from the start of the book, where the author, as a small child, does something horrific to another child and feels no regret about it:

Abruptly, Syd kicked my backpack from where it sat at my feet, knocking everything to the ground. “You know what?” she said. “I don’t care. Your house sucks, and so do you.” The tantrum was meaningless, something she’d done to get my attention like countless times before. But she’d picked the wrong day to start a fight. Looking at Syd I knew that I never wanted to see her again. I figured this message should have been clear after I locked her outside my house in the dead of night. But evidently I needed to send a more direct message. Without a word, I leaned down to collect my things. We carried pencil boxes back then. Mine was pink with Hello Kitty characters and full of sharpened yellow #2s. I grabbed one, stood up, and jammed it into the side of her head. The pencil splintered and part of it lodged in her neck. Syd started screaming and the other kids understandably lost it. Meanwhile, I was in a daze. The pressure was gone. But, unlike every other time I’d done something bad, my physical attack on Syd had resulted in something different, a sort of euphoria. I walked away from the scene blissfully at ease. For weeks I’d been engaging in all manner of subversive behavior to make the pressure disappear and none of it had worked. But now—with that one violent act—all traces of pressure were eradicated. Not just gone but replaced with a deep sense of peace. It was like I’d discovered a fast track to tranquility, one that was equal parts efficacy and madness. None of it made sense, but I didn’t care. I wandered around in a stupor for a while. Then I went home and calmly told my mom what had happened. “WHAT THE HELL WAS GOING THROUGH YOUR MIND?” my father wanted to know. I was sitting at the foot of my bed later that night. Both my parents stood before me, demanding answers. But I didn’t have any. “Nothing,” I said. “I don’t know. I just did it.” “And you’re not sorry?” Dad was frustrated and irritable. He’d just returned from another work trip, and they’d been fighting. “Yes! I said I was sorry!” I exclaimed. I’d even already written Syd an apology letter. “So why is everyone still so mad?” “Because you’re not sorry,” Mom said quietly. “Not really. Not in your heart.” Then she looked at me as if I was a stranger. It paralyzed me, that look. It was the same expression I’d seen on Ava’s face the day we played house. It was a look of hazy recognition, as if to say, “There’s something off about you. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but I can feel it.” My stomach lurched as though I’d been punched. I hated the way my mother stared at me that night. She’d never done it before, and I wanted her to stop. Seeing her look at me that way was like being observed by someone who didn’t know me at all. Suddenly, I was furious with myself for telling the truth. It hadn’t helped anyone “understand.” If anything, it had made everyone more confused, including me. Anxious to make things right, I stood up and tried to hug her, but she lifted her hand to stop me.

Memoirs are tough cookies. Who’s there to correct the writer’s memory when it’s wrong? What kind of work is a memoir?

A staunch editor may fact-check everything before a book is published, but the basis of most memoirs is still the memories and wants of the writer, who’s often the protagonist of their own story. I’m not trying to say the author of this book has tried to falsify their story, only pointing to the main issues with most books.

Events like the quoted one above occur throughout the book: something seemingly exceptional happens and then the author describes the event. This goes on and on, much like a jaded after-school special. Adults are dramatised into standing-around stereotypes, flabbergasted at what the author does as a child.

A line from Who Framed Roger Rabbit? came to mind. “I’m not bad,” Jessica Rabbit says. “I’m just drawn that way.” I could relate. I, too, was just drawn that way.

The author doesn’t shift blame anywhere and instead shows signs of what most children display when affected by deeply moving issues: they feel out of place, disoriented, and, at least for a time, are undiagnosed and hence untreated; instead, they might be misdiagnosed. In the case of antisocial personality disorder (generally speaking, what psychopathy is called today), the affected can be interpreted as malicious and callous with intent, not because of a disorder that affects them. Naturally, there is fallout.

The author does recant their thoughts from when they were a child: why not steal the money? Why not jam a pencil into the neck of a kid who’ve just wronged you?

It’s easy for outsiders to quickly feel anger and moral outrage at what antisocial persons do. This book shows a lot of those scenarios in the author’s adolescence.

The teen years show love problems, but not the usual kind that people have. In this book, there’s little fear or trepidation about engagement with people. Also: what’s love to someone who may suffer from severe empathy issues?

People who demonstrate extreme reactions and behaviors are sometimes diagnosed as having a mental illness or personality disorder. But what’s important is that these extremes extend in both directions. We learned that in addition to those who experience too much emotion, there are others who experience too little. Their personality types are not categorized by the presence of feeling but by its absence. Not surprisingly, these were the personality types that interested me the most.

Listening in on the author’s discussion with their father about having a personality disorder is a strange thing: talking with a parent about a very difficult subject, being diagnosed on a level that fundamentally explains your functions as a human being, can be monumentally difficult; on the other hand: what do you experience when you don’t feel fear like most people?

To me, the author’s problem isn’t ‘sociopathy’; they are most definitely not barred in by their eventual diagnosis. Their writing is another thing: rather than merely painting a picture of strenuous or even harrowing passages of time like authors such as Carrère or Barthes expertly do and did, respectively, Gagne’s writing comes across as slightly soppy, a wail tale. The book isn’t a failure. The author picks on something that is very much needed: literature about growing up and living, in adult life, with what’s likely a limiting personality disorder. It’s not a definition of one’s life nor is it a stain.

I’m glad the author didn’t deep-dive into clinical definitions nor literature or pop matters, like the hellspawn that is the book American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis. The book contains interactions that are valuably written. I felt pathos for the author as they grew up. It takes guts to be gentle and kind, and it takes massive powers to constantly be aware of and navigate through human waters when a personality disorder interferes.