Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

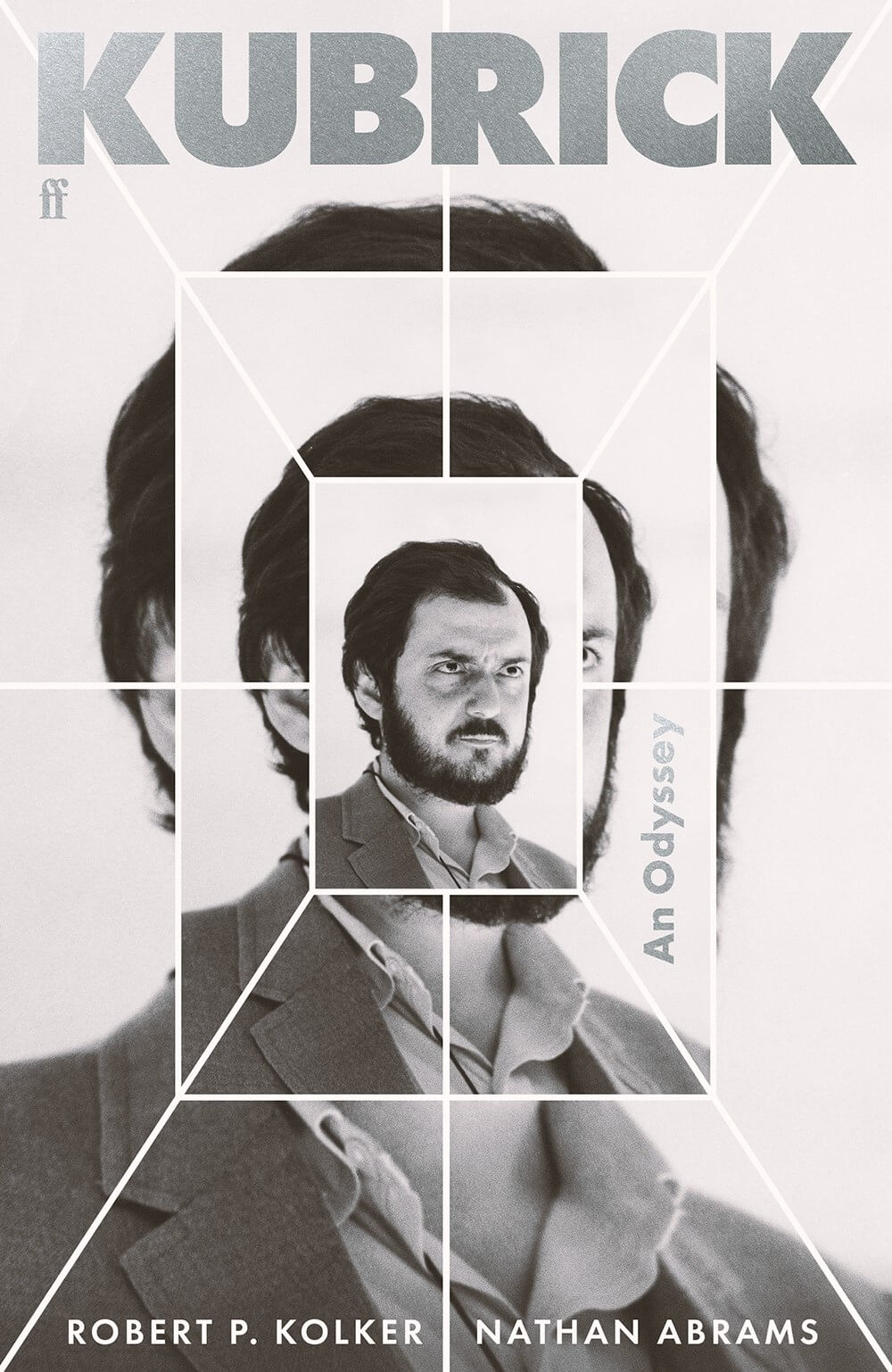

This is a pretty straightforward book about Stanley Kubrick’s life in cinema. It’s written from a popular perspective, which means no masters degree in film or a subscription to Les Cahiers du cinéma is required to read this book.

The book is chronological, although it starts with his death and then moves from his youth to death and slightly beyond. Even though Kubrick is larger than life in some ways—my favourite-ever film director—this book is fairly dry; there’s no action on the pages, and events come acoss without much life in a way that makes having seen the films required to understand some of Kubrick’s choices.

The marriage to Toba was a bad fit. They were too young; Stanley was too ambitious. There were films to be made and a life in which, finally, Toba had no place.

Finally? Strange, even in context.

Speaking of which, there are a few recants of woman actors that feel strange to me, especially in telling of how Shelley Duvall was horribly treated during the filming of The Shining; one of Kubrick’s daughters, Vivian, made a making-of documentary while The Shining was made:

In a later interview in Vivian’s film, Duvall is more composed and admits that ‘he knew he was getting more out of me’ by being tough. But the damage was done. These confrontations have been used to confirm the myth of Kubrick the misogynist ogre, when in fact they were meant to indicate how he worked to get exactly what he wanted, to achieve what Leon Vitali calls the ‘emotional temperature’ that he was looking for. The crew had meetings – not seen in the documentary – about how he wanted them to treat Duvall. ‘The only way we’re going to get Shelley to cry and be miserable today is if we’re shitty to her,’ he said. ‘I’ll be shitty to her, Brian [Cook], you’ll be shitty to her, Terry [Needham, assistant director], you’ll be shitty to her.’ Then he told assistant director Michael Stevenson and production manager Doug Twiddy to be nice, fatherly figures to her. The ganging up was indeed atrocious, yet the result was a fearful, but finally brave, character, who defeats Jack the monster and saves her son.

Sure, Duvall’s performance is astounding, but…well. If she was ultimately happy, then…but was she happy? The authors say no but still believe her own words are not entirely believable:

Shelley survived, despite a miserably exploitative appearance in 2016 on Dr. Phil – a syndicated American television show in which pop psychiatric advice was administered – in which she appeared haggard, semi-coherent, and emotionally troubled, expanding the legend about how Kubrick’s abusive behaviour ruined her. What was not mentioned were the years of fruitful producing of children’s television that Duvall undertook after The Shining and the cold fact that Kubrick elicited from her a performance of anxious, hysterical strength that matched Nicholson’s depiction of Jack’s growing madness. Duvall follows a pattern of actors who are seemingly upset by Kubrick’s rigorous demands and then, in retrospect, touched by his kind attention.

The question is at this point: could Stanley Kubrick do wrong? The authors don’t seem to believe so, from the perspective of people they indicate that Kubrick used for his purposes. I don’t see that they’ve interviewed some of the people they write about, for example, Duvall, but that doesn’t stop them from thinking about it all. Weird.

There are also sloppy things in this book, mainly repetition; I lost count of the number of times that some things were repeated. Sloppy editing? Perhaps. Then there’s also vulgar use of some terms, like ‘psychopathic’, while writing about Full Metal Jacket:

He stripped back most of the episodes in the book depicting physical assault – except for the brutal beating of Pyle by his bunkmates – making the final outburst of violence almost, but not quite, unexpected. In addition, he created a scene showing how Pyle became a very good rifleman – in the book, this is briefly mentioned in one line – an elegant solution that created the ironies of Pyle’s transformation into a psychopathic murderer.

Also, the book contains speculation that were OK if my old grandmother would have spouted it, although I wouldn’t have accepted it then, either.

Perhaps this toxic atmosphere, combined with Kubrick’s other habits, such as his fondness for Big Macs, affected his health and led to his early death.

Perhaps. Sigh.

Having griped about all that, some good things exist in this book. One thing I like about the book is how the authors return1 to some themes, stories, and books; for example, Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, which Kubrick turned into his last film, Eyes Wide Shut. It took him over 40 years to make that film.

Zweig and Schnitzler. For all his admiration for Stefan Zweig, it was Arthur Schnitzler who ranked higher in Kubrick’s esteem. Schnitzler’s obsession with sex and death – he was a duelling, philandering, cosmopolitan polymath, who kept a diary of his promiscuous sexual life including, it is said, every orgasm he had ever had – appealed to Kubrick, so much so that he kept Schnitzler, and in particular his novella Traumnovelle, in mind to the very end of his life. Schnitzler, Zweig, and Freud. ‘The whole Freudian thing’, as his long-time assistant Leon Vitali puts it. He was fascinated by ‘the interplay and psychology in relationships, what made them tick and what made them crumble’; how human relationships can dissolve and split so easily. Schnitzler, ‘perhaps the most famous portrayer of adultery in literature written in German’, pulled him towards the Zweig property, since both, as well as Freud, focused on the sexual lives of the bourgeoisie of turn‐of‐the‐century Vienna. Zweig’s and Schnitzler’s treatment of bourgeois sex and sexuality appealed to Kubrick. Sex was always on his mind and always treated in one way or another in his films where he explored the crises of the male libido – sexual odysseys, fantasies, marriage, jealousy, fidelity, adultery, and dysfunctional family dynamics. These themes had shown up frequently in the early films and writings; sexual imagery had permeated his work from his photography for Look magazine onwards. So did children. Zweig’s story was particularly appealing because there was a child at its centre. Kubrick’s interest in children and childhood can be traced back to his earliest photography. As a teenage photographer, his first images were those of his family and friends, the latter themselves children. This continued when he graduated from high school and began working for Look full-time. Had it been made, Burning Secret would have realized his interest in children and childhood. Schnitzler would have to wait another forty years.

Kubrick employed a few readers who were tasked with trying to find stories that he could turn into film.

Kubrick had his Empyrean readers peruse literary novels concerned with sex, marriage, and extramarital relationships, requesting reader reports on the likes of Dostoevsky’s The Eternal Husband and Ian McEwan’s collection of short stories, First Love, Last Rites. Kubrick’s lifelong obsession with sexuality and jealousy had reached its transcendent state. ‘He was deeply “obsessed” with jealousy – jealousy is the real topic of Traumnovelle, sexuality a sub-category,’ Jan Harlan said. ‘We talked often about it, that jealousy is the most destructive element in all human relationships – it starts with siblings and ends in excessive nationalism and war … He was interested to make a film about it for years and years … Stanley and I had long talks about this. He thought Schnitzler hit the spot.’

We follow Kubrick’s thoughts about the book through decades, for example, during the making of The Shining:

Despite his concentration on The Shining, despite his telling an interviewer in 1980, ‘When I’m making a film I have never had another film which I knew I wanted to do, I’ve never found two stories at the same time,’ Stanley kept thinking about Traumnovelle. While reading his copy of King’s novel back in 1977, he had written in the margin: A hotel is sex-oriented rooms, beds, places to go. sleepy boredom leads to sex. could a scene start like this and turn into something horrible? should Jack have fantasies? say, a jealous fantasy of Wendy in bed with others … A brief scene? RHAPSODY IDEA!! Plant early on an innocent admission by Wendy that she has ‘thoughts’ but never has – never would be unfaithful. ‘What kind of thoughts.’

Reading about Supertoys, the film idea that would become realised by Kubrick’s friend Steven Spielberg, in relation to artificial intelligence, is both wondrous and gives a view into how far Kubrick would go in gaining knowledge about a story:

Kubrick’s vision for ‘Supertoys’ had by now become extremely ambitious. Back in 1988, Kubrick had read Mind Children, a book about artificial intelligence by Hans Moravec, a robotics professor at Carnegie Mellon. He even convinced Moravec to send him the advance chapters of his follow-up book. Within a year, Kubrick enlisted Aldiss once again, wanting him to incorporate the latest theories of AI in a story set in a post-global warming future. Never mind that Stanley had treated him badly, penalizing him for breach of contract in the late 1970s, Aldiss returned to what he called ‘Castle Kubrick’. The story would marry a fairy-tale-like quest with a high-tech and hard-edged future. Kubrick wanted the robots to reflect the most up-to-date thinking on AI, influenced by Moravec’s work, which he passed on to successive writers. He also read Marvin Minsky’s The Society of Mind published in 1988, as well as Arthur Koestler’s 1967 The Ghost in the Machine, whose argument about the relationship between mind and body he returned to throughout his life. He pursued the Pinocchio idea, which he had mentioned to Aldiss back in 1976. Leon Vitali had been reading the original version to his little boy, and shortly afterwards started finding copies of it lying around Childwickbury. ‘So I asked him if he was reading it, and we talked about its darkness, and he wanted to know if I wasn’t worried reading it to my son. I said I felt the darkness in it was a positive thing and he started telling me how he thought it could fit integrally into AI.’ Pinocchio was one of Stanley’s favourite fairy tales, too. ‘This shows a side of Stanley that people haven’t seen before, which was a very deeply emotional and lonely side,’ says Spielberg. The movie would depict ‘a different romanticism that hasn’t been shown on the screen’, Jan Harlan said. ‘The whole idea of an artificial being feeling genuine love and a human genuinely loving an artificial being. This is quite new territory.’

Aside from Traumnovelle, Kubrick wanted to make The Aryan Papers, a film about the Holocaust. Just as with his film about Napoleon Bonaparte, he never got time to make The Aryan Papers. His wife Christiane remembers this.

‘I read all the material Stanley collected with his usual care and became depressed, even though I knew everything,’ Christiane said: He was also in a state of depression, because he realized it was an impossible film. It’s impossible to direct the Holocaust unless it’s a documentary. If you show the atrocities as they actually happened, it would entail the total destruction of the actors. Stanley said he could not instruct actors how to liquidate others and could not explain the motives for the killing. ‘I will die from this,’ he said, ‘and the actors will die, too, not to mention the audience.’

David Mikics’s Stanley Kubrick is whip-smart and snappier compared with this book. The big Taschen book The Stanley Kubrick Archives is another big tip. It’s nearly worth the price just to read the review of 2001, written by a young girl; that review smashes every other review of that film that I’ve read.

All in all, it’s clear that the authors of this book have a lot of time and passion for Kubrick; they’ve previously had works published both about Kubrick and his works. I wish this book were edited tightly. To quote from the start of the book:

Orson Welles once commented that, during editing, a film-maker should look at his favourite images and cut them. ‘When I’m editing,’ Kubrick told Gene Siskel, ‘my identity changes from that of a writer or a director to that of an editor. I am no longer concerned with how much time or money it cost to shoot a given scene. I cut everything to the bone and get rid of anything that doesn’t contribute to the total effect of the film.’

This is not the same as the nonsensical repetition that I’ve mentioned. ↩