Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

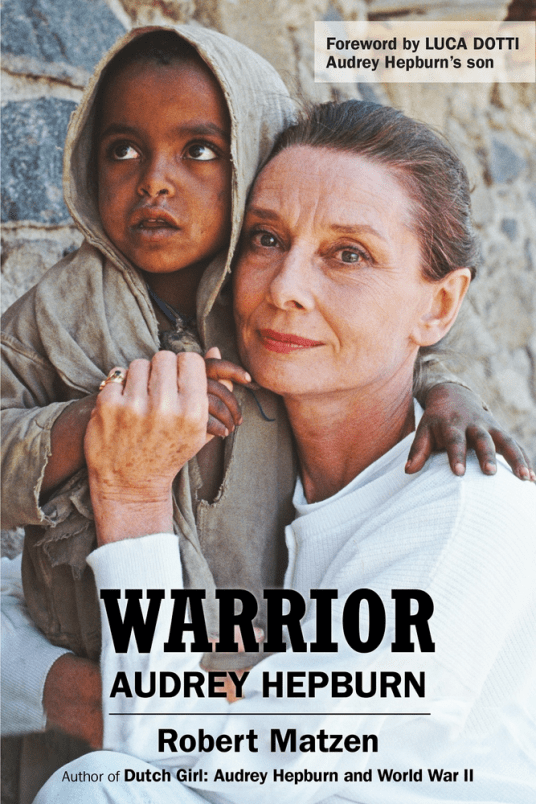

This book is hagiography. It lauds Audrey Hepburn, one of the most prominent American Hollywood actors of the 1950s and 1960s. The book is authored by a man who wrote Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II and is close to Luca Dotti, one of Hepburn’s sons.

If hagiography would be all that there is to this book, it would be junk.

Thankfully, this book is more than applause and apotheosis.

She had heard that one of the children was asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “Alive” was the response. Audrey could see a nightmare in the making not just for Ecuador but for the world, and it rattled her. They were growing up wild, these children of the streets, with no education, no moral compass, and total susceptibility to all the evils of the world. By adulthood, those who survived would be monsters without conscience. That realization crystallized UNICEF’s street-children mission in her mind.

Audrey Hepburn was humanitarian and helped people who weren’t as fortunate as she was. She made more of a career as an UNICEF ambassador than an actress; she went a very long way to help people who lived in appalling conditions. There is no doubt in my mind that she tried to better these conditions in many ways, which are on display in this book.

“My mother didn’t take herself seriously,” said Sean. “She used to say, ‘I take what I do seriously, but I don’t take myself seriously.’”

This book lifts a shroud off Hepburn’s persona as constructed by magazines.

When she was five both her parents embraced Germany’s savior Adolf Hitler, tucked their daughter in the Netherlands with family, and traveled to Munich to meet the Führer. Soon Audrey’s father separated from Dutch Baroness Ella van Heemstra, Audrey’s mother, to work for the growing German empire. Her mother retained pro-Nazi ties for another eight years, all of which became a set of secrets locked in Audrey’s soul for a lifetime.

There are some bizarre omissions throughout the book. For example, there is mention of Hepburn’s support for Live Aid, but nothing said about how proceeds from that gala were emptied by the Ethiopian government to buy arms, something which Bob Geldof was warned about but ignored.

Some very personal details are included:

February 1980. Eight years before the Ethiopia trip, Audrey had secluded herself at 615 North Beverly Drive in Beverly Hills during what she called “the worst period of my life.” Divorce proceedings with Dotti were dragging on and when final, she would find herself a signed and sealed two-time loser. So much for chasing love. Her most recent attempt at following her heart had been a crush on actor Ben Gazzara, with whom she worked on the features Bloodline and They All Laughed. But the infatuation went nowhere and she ended They All Laughed feeling lonelier than ever.

It is also clear that Hepburn did her best to try and help people who desperately needed help.

“Many times, people would ask for an interview about UNICEF when they really just wanted to talk about movies,” said Christa Roth. “She would talk an hour about, say, Ethiopia and five minutes about films, but the story would be ten percent UNICEF and ninety percent movies. It bothered her a lot. So we started to restrict the interviews to publications that gave her solid footage. It worked out quite well. She got a lot of coverage.”

She used her name and fame to get money for poor people, which should always grace her name:

This audience had purchased tickets in the range of $25 to $75 each. Hundreds of donors had paid $250 to $500 to rub shoulders with Audrey and one another at the pre-event cocktail hour. Tonight’s gate for UNICEF would total north of $350,000.

I wonder what Hepburn herself would say if she were today interviewed about her life. I doubt she would direct most of the conversation to be about herself, which is why I’m glad this book exists. It shows that anybody can help out, no matter to what extent. On the other hand, the book is garnished with namedroppings that we could do without.

This book suffers a bit from being fragmented. It’s written in an old-school style of writing: paragraphs are quite standalone and some people are portrayed as fairly two-dimensional. Still, on the whole, it’s interesting to read about Hepburn’s selfishness and good heart.