Address change to reviews.pivic.com

This site is changing its address.

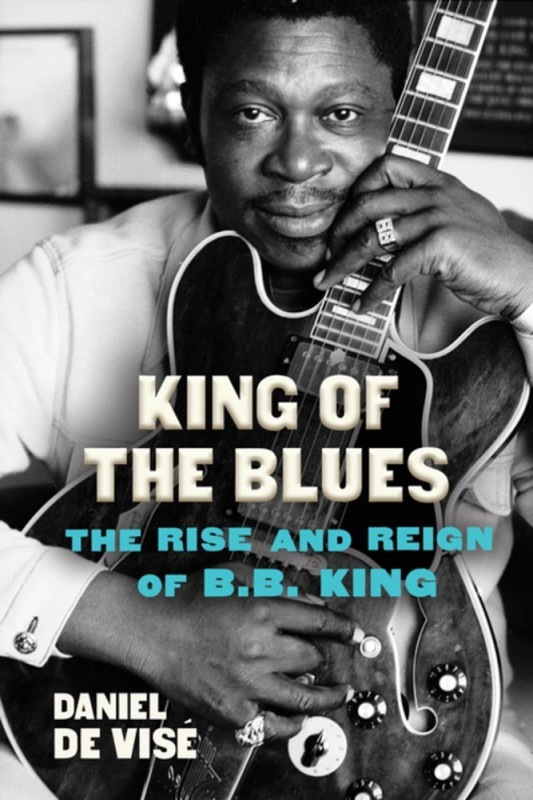

This book starts off slowly but carries a cinder that sparked my interest, mainly in how it contrasted B.B. King’s life with the times during which he lived.

Here’s a hard-working musician who made it into annals of blues, not because that’s where he strived to be, but because he was one hell of a blues player: He wanted to play.

Ask any blues musician what they think of B.B. King and you’ll hear the same accolades and a lot of emotional outbursts. Naturally, there’s far more to a person than that, good and bad.

Our main character was born Riley King in 1925 and grew up a child of the American south, in rural Mississippi. He picked cotton and worked through his days, pushing and hoping for change. His youth and adolescence happened during Jim Crow, lynchings, racist segregation, legal abominations against non-whites, among other types of xenophobia committed against Blacks mainly by whites. Constant fear, segregation, and barriers kept Blacks down. There were more lynchings in Mississippi than in any other American state at the time of King.

The author of this biography, de Visé, does the reader a great service in steeping his story about King’s life in history, both in relation to what went on in the USA on a racial level and in how music evolved, both blues and pop. From how whites were guarded against what started as African music to how blues and rock ‘n’ roll became the favourite pastime of, well, everybody at the time, to how King and his musicians were nearly murdered several times while on the road, this is one rollercoaster-ride of a book, without the need of any kinds of exaggeration. B.B.’s life provided a lot of action, sorrow, and success.

Mississippi in the 1930s was a dystopian society for African Americans, governed by the framework of codified racism known as Jim Crow, after a racist minstrel character. The U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in 1896 that separation of the races was constitutional, so long as Black and white accommodations were “equal.” Luther Henson helped Riley decode the separate-but-equal fiction. African Americans tipped their hats as they passed whites on the streets, but whites did not return the courtesy. African Americans called whites “sir” or “ma’am,” while whites called Blacks by their first names. White pedestrians on sidewalks enjoyed a perpetual right-of-way. Blacks stepped aside.

Mississippi in 1930 spent $31 on a white student, $6 on a Black one.

Apart from the historical context that made every human suffer, the core of psychology that spins around this book is where B.B. King, according to Daniel de Visé, spent a lot of his time both in thought and physical pain: his genitals.

When B.B. King grew up, he taunted a goat that retaliated by butting him straight in his genitals; pair that with a severe case of gonorrhea that a doctor tried to cure by punching a hole in King’s scrotum and adding heavy books on top of it to let out liquids, and you’ve got yourself a situation that makes Greek mythology look kind.

The author, and prior biographer Charles Sawyer, claims that it is likely that B.B. King was not the biological father of any of his children, all fifteen of them, in spite of King’s claims. Still, King cared for all of them in different ways and spent millions of US Dollars on them over the years.

In later years, B.B. would weave an elaborate fiction of fatherhood, acknowledging his low sperm count even as he claimed to have sired several children and falsely asserting that both of his wives had miscarried. The truth—that B.B. probably never stood a chance to father children—remained a closely guarded secret to the end.

While toiling in cotton fields, King wanted money to buy musical equipment. There were singing, long drives, and dreams.

The great blueswomen of the 1920s and early 1930s sang playfully and euphemistically about prostitution, drugs, homosexuality, and sodomy. Much of this content arrived in record stores uncensored: white studio executives and other arbiters of decency didn’t know what they were hearing.

As Peter Guralnick observed, all roads on the great blues trail lead back to Mississippi, to the Delta, if not to any town or plantation in particular.

It’s interesting to see from where King’s influences came:

B.B.’s deejay work opened up a whole new world. The typical Delta bluesman synthesized the styles of the men he heard at the local juke joint into one of his own, with direct and obvious antecedents in the work of his predecessors. B.B., by contrast, drew inspiration from music he heard on records and film reels and radio. His greatest influences were men he had never seen, at least not in person: Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charlie Christian, and T-Bone Walker from Texas; Lonnie Johnson from New Orleans; and Django Reinhardt from Belgium. Never, perhaps, had a blues guitarist drawn from such diverse influences. And now, with an entire radio station at his disposal, B.B.’s ears were about to explode.

It’s also lovely to read of how King wanted his guitar, Lucille, to sound like a voice:

On the night B.B. anthropomorphized his Gibson L-30 guitar into Lucille, he nudged popular music into the future. Where other guitarists had heard scales and chords and arpeggios, B.B. heard a voice. “I wanted to sustain a note like a singer,” he recalled. “I wanted to connect my guitar to human emotions.” He wanted his guitar to sound like Lonnie Johnson’s. He also wanted it to sound like the full-throated tenor of Roy Brown and the silky baritone of Nat Cole.

As King and his big band broke through, there was a lot of action, not at least on the so-called chitlin’ circuit of the American south:

“We were playing one-nighters,” recalled Floyd Newman, B.B.’s affable baritone saxophonist. “We’d go to work at 9 and play till 2. Then we’d get on the bus and go to the next place. The only place you’d get to wash up was at the club. It was rough out there, sleeping on the bus. You had to wash your shirts in the restroom and hang them in the bus to dry.” B.B. and his entourage “really lived off the bus,” recalled tenor saxophonist George Coleman. “Everybody had a box with crackers, sardines, and beans. You didn’t have time to stop at a restaurant because you was jumping from one part of the country to the other at all times. A lot of times, when you got off stage you had to jump right on the bus to get to the next town.”

Not much had changed between the 1930s of King’s early youth and the 1950s, which this paragraph is from:

B.B. and Norman Matthews later recalled that, more than once, the band beheld African American bodies hanging from trees as they journeyed through the Deep South. At such moments, they recalled, the musicians would fall into a sickened silence. Someone would finally break it by asking, “I wonder what they say he did.” Someone else might add, “And you know that at the next gas station, you mess up and it’ll be you.”

King had his own style, fixed in playing, without theatrics:

B.B. had no pompadour, no duck walk, and, frankly, nothing in his repertoire as irresistibly catchy as Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” or Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti.” But B.B. did have a few moves. One was to strike a note on his guitar and then spin his pick hand around and around over his head while the note rang, as if he were magically coaxing the vibrato from the instrument. Another was to plant his hand on his hip and sing in falsetto while gyrating in an effeminate wiggle. Either could bring the house down.

King was not only beloved by audiences but also his peers:

One night in late 1959, B.B. stood at a urinal in the men’s room at Birdland, the New York jazz club, between sets of the Miles Davis Sextet. He was there to see Miles, and the mournful melody of “’Round Midnight” played in his head. A raspy voice broke up his reverie: “Motherfucking, blues-singing B.B. King. Yeah, that’s one cat who plays his ass off. Nigger can blow some nasty blues.” A shiver ran up B.B.’s spine. Miles was also in the men’s room, talking about B.B. That night, the bluesman met the jazzman. Thereafter, whenever they played the same town, B.B. and Miles religiously attended each other’s shows.

There’s also something to be said for King’s insanely laudable work ethics, which one should also sanely question:

Around this time, B.B. was riding shotgun in a Ford van heading from a show in New Orleans to another in Dallas. The night was rainy, and B.B. warned his driver about slick roads. Around Shreveport, B.B. fell asleep. The next thing he felt was “a thump and a bump and a crash, and excruciating pain.” The van had veered off the road and hit a tree. “The tree wound up in my seat,” B.B. recalled. Fortunately, B.B. was no longer there: he hadn’t worn a seatbelt, and the impact had thrown him from the van. He had instinctively raised his right arm, which smashed through the windshield. When B.B. collected himself and took stock, he saw a large flap of flesh dangling from his arm where it had met the windshield. B.B. beheld the white of his own bone. A surgeon dug the glass from B.B.’s partially severed triceps, sewed up the arm with 163 stitches, and apprised him that he owed his life to the good fortune that the windshield glass had missed major arteries. B.B. flirted with the nurses. That night, he made the gig in Dallas. His right hand was useless, so B.B. coaxed sounds from Lucille by hammering the strings against the fret board with his left. His amplifier did the rest.

de Visé writes beautifully of King’s seminal Live at The Regal, a live album that was recorded a few minutes after his fellow musicians were told it would be recorded. It’s one of the most revered and dearly beloved live albums ever, and de Visé whips up the excitement that the album deserves.

When the show was over, the crowd poured out onto Forty-Seventh Street into the frigid Chicago night, many of them hoarse from “yellin’ and screaming and singing along. There were very few people who left there that could actually speak the next day,” Arthur Gathings recalled. “The Regal was Woodstock without the drugs. . . . That’s how much excitement was in the theater that night.”

Live at the Regal was required listening for anyone with a serious interest in either the blues or the electric guitar. Eric Clapton later said the record was “where it really started for me as a young player.” Carlos Santana termed it the “DNA” of rock guitar. Rolling Stone would one day rank it 141st on a list of the 500 greatest albums ever pressed.

In the 1960s, a blues revival, the British Invasion, and a new manager sparked more interest in King. He also started making enough money to fly more often than by bus.

This did not stave off problems: the IRS went for most of King’s money while his marriage was falling apart.

The man had toured for almost fourteen years and performed over 5,000 times when played the Fillmore theatre.

He received standing ovations even before he entered the stage.

Carlos Santana, the guitarist from Tijuana, stood in the audience and beheld his hero through the smoky glare. “The light was hitting him in such a way that all I could see were big tears coming out of his eyes, shining on his black skin,” Santana recalled. “He raised his hand to wipe his eyes, and I saw he was wearing a big ring on his finger that spelled out his name in diamonds. That’s what I remember most— diamonds and tears, sparkling together.”

“I played that night like I’ve never played before,” B.B. recalled. He fed on the energy of his audience, an interaction not unlike the feedback loop between guitar and amplifier that provided Lucille her signature sound. B.B. had been allotted forty-five minutes but played for nearly an hour and a half. All the while, the audience remained on its feet, dancing and leaping, screaming and clapping, frigging, fragging, and frugging. The cheering never really stopped. “It was hard for me to believe that this was happening,” B.B. recalled, “that this communication between me and the flower children was so tight and right.”

There are far more ups and downs in his career, not least because of what he did with U2, which catapulted his sales and made it possible for him to play to far bigger crowds.

There is far more to King’s life than what is detailed in this simple review, and de Visé does a good job at writing of what he felt went down. Sadly, he has not interviewed King himself, but many of King’s relatives, co-musicians and friends. He paints a broad picture of a man whose inner pains were often expressed through his fingers and Lucille; they evolved the blues.

My only gripe about this book has to do with King’s supposed inability to produce children: I think it’s important to write about, but I also think it was written about far too often. Traumas should be excised and displayed when writing a biography, but de Visé couldn’t ask King about it, nor does it serve a deeper psychological purpose other than show how kind King was to count a lot of children as his own even if they weren’t, and how they all collated after King’s death, to get their money. It’s a bit too gossipy and hearsay for me.

I’ve not read a biography on King prior to this book, so I can’t compare it with any others. Nor have I heard a lot of King’s music. In other words: I’m very far from a King expert. On the other hand, I feel that what I’ve heard of King’s music comes alive through most of de Visé’s words, and this book is a solid read from beginning to end: there’s a lot to be said about a writer whose words bring music alive in one’s head, especially when writing about King’s concerts and recordings.

King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King is published by Grove Press and is released on 2021-10-05.